Historic Boyle House, home of county’s namesake, lost

Published 11:26 am Saturday, July 1, 2017

- Boyle County Public Library

A photo provided by the Boyle County Public Library to the Boyle Landmark Trust shows the Boyle House, where Judge John Boyle, the namesake of the county, lived.

A structure that helped define Boyle County and shared its name has been lost, according to the Boyle Landmark Trust.

The Judge Boyle House, one of a dwindling number of remaining “Federal” style homes in the area, has been demolished by the property owner and the rubble cleared away by a salvage company, said Jacob Pankey, chair of the trust.

The trust announced the loss of the historic home, which was built in 1815, with a letter sent to local governments and The Advocate-Messenger.

“The Judge Boyle House was as inspiring as Judge (John) Boyle himself. When Boyle County was established in 1842, the General Assembly insured that the house and farm would be the fundamental landmark of the county. The house sat equidistant between Danville and Harrodsburg,” the letter reads. “… Regrettably, Boyle County citizens today and future generations will only be able to research the architectural marvel that once stood in Boyle County.”

Pankey said the trust tried to work with the private property owners who hold the land the house stood on to restore or relocate the structure, or to sell the land to someone interested in preservation. But those efforts failed and the owners had the house demolished so a new house could be built in the same location, he said.

Pankey and fellow Boyle Landmark Trust member Barbara Hulette did not name the property owners because they want the focus to remain on the legacy of the Boyle House — and the need to protect other historic structures that still stand but are threatened.

“This is the first time that the trust has done an announcement like this,” Pankey said. “We think it is important that the community, Boyle County itself, knows of the loss.”

Hulette said while there was damage to exterior brickwork and a minor issue with water runoff affecting the foundation, the interior of the Boyle House was still in excellent condition prior to the demolition.

It would have cost an estimated $100,000 to repair brickwork on the structure, while the foundational issue may have been corrected by installing gutters and downspouts, she said.

“It was so savable,” she said.

Pankey and Hulette said the trust worked with the Boyle House owners in the same ways it does with other property owners with endangered historic structures. The trust provided educational information about rehabilitation and preservation; it offered to help the owners qualify for state and federal tax credits available when preservation work is done; and it tried to find outside funding to purchase the land the house sat on or move the house to another location.

Hulette said the estimated cost to move the house was $300,000, which put that option far outside the realm of possibility. The owners initially said they would be interested if someone else wanted to buy the land the house sits on, but trust members didn’t expect they could find a buyer.

“But unbelievably, a buyer surfaced and made an offer,” Hulette said. “But they turned it down. … It was something the owners didn’t really want to keep themselves. They wanted a brand new house. Since it is their property and their house, that is their right.”

Pankey said the Boyle House had always been privately owned, and it’s location was set so far back on private land that it wasn’t visible from any public roads.

The previous owner, Joe Keller, worked to get the house on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980, according to the NRHP database.

“Embodying the traditional features of the Federal style as found in Boyle and surrounding Bluegrass counties, the Boyle House achieves distinction because of the treatment of the recessed panels of the facade, the delicate interior moldings and its excellent state of preservation,” the building’s entry in the register reads.

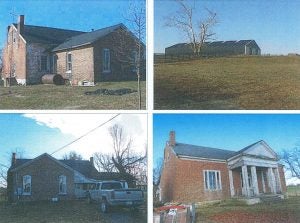

Boyle County PVA

Photos from the Boyle County Property Valuation Administrator depict structures including the Boyle House on the entry for the property.

Property Valuation Administrator records show the current owners purchased the farm the house sat on in 1998 for $550,000. The tract of land is more than 200 acres, split across Boyle and Mercer counties.

Pankey said having a structure placed on the National Register does not provide any protections against demolition.

Hulette said the register “gives credence” to a property’s importance.

“It deems the property extremely important — one that we wouldn’t want to lose, but that does not ever guarantee that it cannot come down.”

Pankey said if he were ranking buildings of historical importance in Boyle County, the Boyle House would be near the top with structures such as those named for the McDowell family.

“There are few houses in my opinion that hold as much significance as this property does,” he said.

History of the house

According to the Boyle House’s entry on the National Register of Historic Places, it was constructed around 1815 and 1816. As was common for homes constructed at the time, it was made using materials at the site of the structure, meaning bricks were made from local soil and wood came from area trees, Pankey said.

National Register of Historic Places

A photo from the Boyle House’s 1980 entry in the National Register of Historic Places shows the front of the house.

The house’s register entry states that Judge John Boyle was “one of Kentucky’s most distinguished lawyers and politicians and the man for whom Boyle County is named.”

“Boyle served three successive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives before he was appointed to the Kentucky Court of Appeals, where he acted as chief justice for 16 years during one of the most politically active periods in the state’s early history,” the entry reads.

Boyle had been dead for seven years when, in 1842, Boyle County was created and named after him, according to the book “Historic Homes of Boyle County” by Calvin Fackler.

Fackler’s book states that “we do not know the fully story” of why Boyle was chosen as the namesake for the county, only that a historian recorded “it was so called in honor of John Boyle.”

In the legislative act that created Boyle County, the Boyle House was described as part of the new county’s boundaries:

“…thence down and with said river to a point thereon from which a due east and west line therefrom will include the house, yard and garden of the late Judge Boyle.”

The same act declares that the land of Boyle County be “stricken from Mercer and Lincoln counties and erected into one distinct and separate county, to be called Boyle, in honor of Kentucky’s distinguished jurist John Boyle.”

Fackler notes it was “unlikely that (Judge Boyle would have) been a mover for its formation,” referring to the new county.

“… when the event did happen, his farm was divided by the Mercer-Boyle line,” Fackler wrote.

Protecting other properties

Pankey said rather than getting down about the loss of the Boyle House, “it really has invigorated the trust and the revolving fund initiative.”

The trust is in the process of starting the revolving fund, which would be used to fund the saving and restoration of important historical properties.

Hulette, who is chair of the revolving fund initiative, said the trust expects to select the first project for the fund soon, after which it will begin fundraising.

“We have to give the people a reason as to why they are giving, so we have to choose something that we think the public might be interested in,” she said. “… We have to be very specific with their money and guard their money for that real reason only.”

Hulette said while members of the trust are passionate about saving important pieces of history, when it comes to actually preventing the loss of a historic building, “it boils down to, ‘show us your money.’”

“That’s why we’re so desperately trying to get this revolving fund kicked off, because once we have options available to place on properties, then we can do more, we can save more,” she said.

“We can shift from the education and advocacy point to (having) more of a direct impact,” Pankey said.

Behind the scenes

The trust is continuing to work to save other historic properties in Boyle County, but those negotiations and conversations with private property owners are often kept out of the public eye because the property owners wouldn’t work with the trust otherwise, Pankey said.

“In all situations, we do not bash people; we are respectful of their ownership,” Hulette said. “We are very respectful of their ownership because someone else owns the land and the house; we don’t.”

Pankey said the reason members of the trust were able to visit the Boyle House before it was demolished and at least attempt to help save it was because they were “cordial” and weren’t shedding light on the situation publicly.

“We are currently in — but we can’t mention — other projects,” Pankey said. “We are working with individuals and organizations to save properties. It just comes with the territory of this type of work.”

But there are also threatened historical properties that fall in the public spotlight or for some reason do not require such quiet dealings.

One house the trust can talk about, and which it has included in its Landmarks to Watch brochure, is the Samuel McDowell House, better known as Pleasantvale.

“In somewhat of a similar fashion, it is on private land and is not accessible by any public road,” Pankey said.

“Two different families own the land where this house is — you might say ‘falling down.’ It’s not standing; it’s partially standing,” Hulette said. “There have been valiant attempts at recognizing that the Samuel McDowell House needs saving, and it’s going to require a lot of money and a lot of willingness (from owners).”

Pankey said working to save buildings like the Boyle House and the Samuel McDowell House is important because they are “silent structures that tell our history.”

“They are silent people in many ways, and they cannot speak for themselves,” he said. “But as we all know, the phrase is, ‘if these walls could talk.’”