Very little getting out of jail free in Boyle, Mercer

Published 1:27 pm Saturday, September 30, 2017

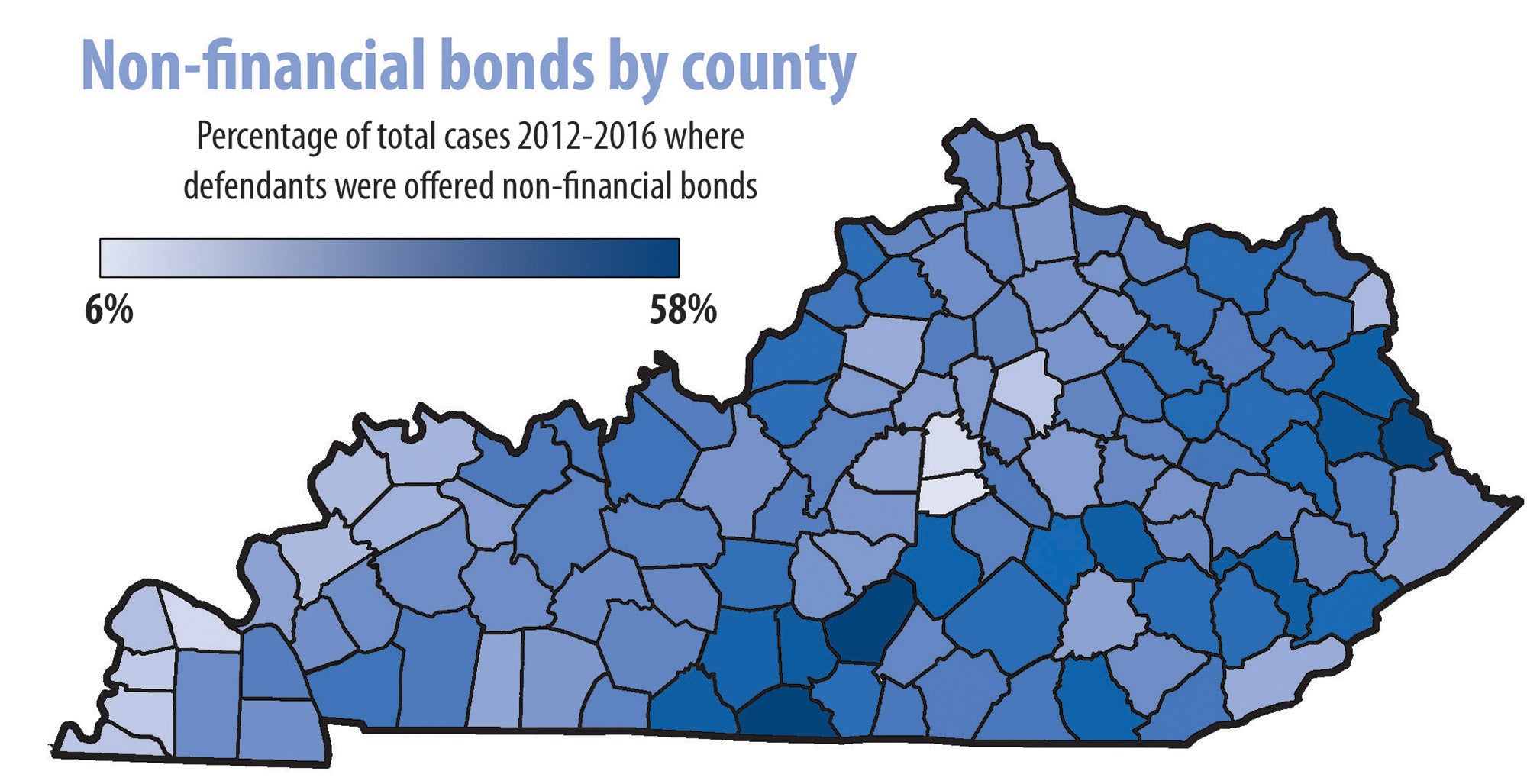

- (Graphic by Ben Kleppinger/Source: AOC report on types of bonds, 2012-2016) Boyle and Mercer counties had the lowest and second-lowest rates of non-financial bonds for defendants in the state from 2012 to 2016, according to statistics provided by the Administrative Office of the Courts. Boyle County defendants were offered non-financial bonds 5.65 percent of the time, while Mercer County's rate was 7.69 percent. The statewide average is 36.8 percent; 44 counties offer non-financial bonds more than 40 percent of the time; 13 counties offer non-financial bonds less than 20 percent of the time.

AOC report: Two counties offer defendants non-financial bonds at lowest rates in state

Roger Hartner isn’t shy talking about the events leading up to his son’s death.

“He had his first overdose a week after they took his child,” Hartner said during an interview in September at The Advocate-Messenger.

Hartner, a tall and powerful presence in any room with a booming voice to match, didn’t mask his emotion as he explained how his son, who was disabled and “had problems” but loved his kid, spiraled into drugs after his kid was taken away.

“That did things to my son that you can’t know,” he said.

Hartner also doesn’t pull punches on who he blames for causing his son’s death: the judicial system in Boyle and Mercer counties, which he says hindered, rather than helped his son when he was vulnerable.

“My son had been in and out of the system in other counties around here and of course in Boyle County — for drugs,” Hartner said. “And in other counties, he had been released on his own recognizance many times, because he was a local person. They kind of knew our family, so they would release (him). But that never happened here in Boyle County.”

Hartner believes keeping people who are too poor to pay a financial bond locked up in prison contributes to those people’s problems. He said he thinks it causes them to lose jobs, lose homes; it erodes their relationships; it turns them into social pariahs even as it introduces them to the only people who will befriend social pariahs — drug dealers.

Distressed after his son’s death and fearful that what he witnessed could be repeated for others, Hartner asked the Administrative Office of the Courts for a report detailing the rates of non-financial bonds among Kentucky’s 120 counties.

Hartner expected to find that Boyle County would have a low rate, but the results — compiled by Daniel Sturtevant and Tammy Manley with Research and Statistics in the AOC’s Department of Shared Services — blew him away.

The report shows that from 2012 to 2016, Boyle County courts offered defendants non-financial bonds — allowing them to leave jail without paying money — at the lowest rate in the state: 5.65 percent of the time. Mercer County, which shares the 50th circuit and district courts with Boyle, was the second-lowest in the state, offering non-financial bonds 7.69 percent of the time.

As a state average, Kentucky courts offered non-financial bonds to defendants in 36.8 percent of cases, according to the report. A total of 44 counties in the state offered non-financial bonds more than 40 percent of the time, while 13 counties had a rate lower than 20 percent, analysis of the report by The Advocate-Messenger shows.

Only one other Kentucky county besides Boyle and Mercer — McCracken in the far western corner of the state — had a non-financial bond rate in the single digits (8.58 percent), the analysis shows.

“If we’re 30 percent worse in allowing people out of jail, that equates to a jail population inflated by 30 percent,” Hartner said. “If you do the math — and I happen to love to do math … that would be an average fewer inmates of 105 inmates every day.”

According to Kentucky Pretrial Services, “there is no preferred ratio of non-financial bail vs. financial bail” that counties are encouraged to obtain. However, the agency noted in a response to the newspaper, “Nationally, pretrial justice reform calls for the removal of cash as a consideration of release in that the poor are inherently penalized. In Kentucky, our statutes support release of all individuals assessed as low or moderate risk, who have been determined by the courts not to be (a) flight risk or danger to (the) community.”

One effort to reduce the effects of financial bonds on people unable to pay them is the “Pretrial Integrity and Safety Act,” which is co-sponsored by Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Cali.), according to Pretrial Services.

Pretrial Services also provided examples of how financial bonds can “penalize the poor.” In one scenario, two women are charged with shoplifting — one of them who has worked for minimum wage all her life; the other who “has a hefty bank account.”

“Both women are arrested and neither has a criminal history,” Pretrial Services wrote in its theoretical example. “Pretrial assesses them as low risk. The judge believes that restitution should be recouped and all potential fines/fees covered and sets $500 full cash on both.

“In the judge’s mind, this is justified as the defendant could plead guilty; however, per the 14th Amendment, all defendants are presumed innocent until proven guilty. Who in this scenario will be the person to be released? Five-hundred dollars to (the poor woman) might as well be $5,000; she doesn’t have it. (The rich woman) easily posts bail and is released.”

In a second example, Pretrial Services offered a scenario where two men of differing incomes are charged with armed robbery. Both are given a bail of $100,000, which the richer of the two, “Jack,” is able to afford.

“Did Jack posting $100,000 make the community more safe?” the scenario reads.

Hartner has his own real-life example in his son.

“The judges and prosecutors in this county are largely culpable for our drug problem, and I have proof,” he said. “Has the drug situation improved with all their keeping and putting people in jail? It’s gotten worse. So don’t try to tell me they’re being hard and tough on people — they’re doing just the opposite. They’re causing more problems.”

The Advocate-Messenger provided copies of the AOC report to 50th Circuit Court Judge Darren Peckler and 50th District Court Judge Jeff Dotson, along with a request for comment last week. Neither judge had responded as of Friday afternoon.

Boyle County Attorney Lynne Dean said Boyle County’s non-financial bond rate may appear as low as it does because Boyle County offers a lot of bonds with bail credit for time served. Typically, a defendant who is put in jail and given a financial bond can earn $100 per day in jail toward payment of a reduced bond amount, she explained. It can often take 10 days for defendants to earn enough in bail credit to be released, she said.

Such bail-credit bonds are “still considered financial bonds” in the AOC report, she said.

Dean said she believes in many cases, being required to remain in jail helps some defendants who have drug problems “sober up and be aware” of what’s going on. She said she’s seen defendants decline to enter drug treatment programs when they are first booked into jail, then change their mind and seek help after several days.

Dean said she would be against creating “a revolving door with the jail, just to decrease the population there.”

“We feel like there needs to be some accountability, but also some protections in place for (defendants),” she said, adding that she has objected in some cases to letting people out of jail because circumstances “were so serious that they might be a danger to themselves.”

“I’ve had parents come to me and say, ‘please don’t let him or her out today. If you do, I’m afraid that he or she might be dead,'” Dean said. “In those situations, I’m inclined to ask the judge to add some additional conditions (for release).”

Dean said she also thinks the size of Boyle County makes it more difficult to release as many defendants as in larger counties.

“It’s tougher in small towns because we know these folks so well,” she said. “I’ve had people that have been assessed low-risk that I’m just like, ‘I cannot believe this person is low-risk.’ … I think in a small town, it’s easier for us to say, ‘OK, what’s the risk level,’ and them to say, ‘he’s low risk,’ and us to say, ‘wait a minute, how is he possibly low-risk?'”

Dean said literature on bonds includes the idea that people shouldn’t be punished because they are poor.

“I think we do a fairly good job of trying to prevent that from happening,” she said. “… Maybe we could improve to some extent. I think we are always talking, at this point, about what we can do better.”

Dean said increasing the rate of non-financial bonds in Boyle County would “probably have some impact on the population of the jail.”

“I don’t think it would solve the issues that we’re having at the jail,” she said.

Dean said releasing people on their own recognizance also presents the courts with a different set of problems.

“Many times, we will let somebody out with an ROR (released on own recognizance bond) … if that person has a drug problem, more times than not, they won’t show up to court and we’ll end up having to put a financial condition on that person,” she said.

Dean said the “main advantage” of using bail-credit bonds instead of non-financial bonds “is having the opportunity to sober up, where they can make better decisions, and the community is protected during that time period an the individual is protected during that time period.”

Dean noted she believes the way the bond data is presented in the AOC report makes it “difficult to interpret.”

The report lists the total number of cases in every county in the state from Jan. 1, 2012, through Dec. 31, 2016. For each county, the cases are broken down by which type of financial bond was offered: administrative release, non-financial, financial or no bond (cases where a judge ruled the defendant was dangerous enough or the crime serious enough that no bond should be offered).

The report does not differentiate between individual cases and defendants — if someone was in jail for three different cases, that shows up in the report as three cases, not one, according to the report. And if someone meets the conditions for release on one bond but is kept in jail due to another bond, both cases would show up as unreleased, the preface to the report explains.

Dean said Boyle County handles defendants the way it does because it cares about them.

“When you get to know these people, you do come to care about them and you want them to better themselves,” she said. “You don’t want to prosecute them, you want to help them if you can. That’s why we make the decisions we make, really, by and large.”

Hartner is anything but satisfied with the status quo.

“I’m going radical,” he said. “… We need someone in this county to say ‘it’s time for a change and hell-be-damned what the rest of the state is doing, hell-be-damned what the rest of the country is doing.”

Hartner said he believes a main source of the county’s drug and jail problems “comes straight from Fourth and Main — and this report points that finger directly.”

“No one can hurt me — I’m bigger than most people. Let ’em try to hurt me. My son is dead; they can say what they want,” he said. “… They know damn well what the problem is.”