Boyle County EMS receives award for pediatric readiness

Published 7:52 am Thursday, July 26, 2018

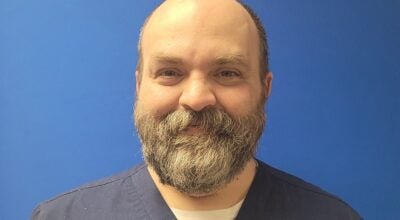

- Bobbie Curd/bcurd@amnews.com Mike Rogers, a paramedic with Boyle County EMS and the education coordinator, says the new child harnesses they were able to get are now on all its frontline trucks. "It's such a simple thing, yet makes a huge difference."

Mike Rogers says when you’re a first responder, being proactive is the name of the game. As education coordinator for Boyle County EMS, Rogers recently spearheaded a program enabling EMS to become more able to treat pediatric patients in the community.

Boyle EMS was recognized for its part in the voluntary program through the Kentucky Emergency Medical Services for Children, meeting criteria established by the organization based on recommendations and guidelines, and was presented with an award of excellence for its preparedness in pediatric care.

Bobbie Curd/bcurd@amnews.com

Boyle County EMS received an award for its participation in a program aimed to improve pediatric emergency care.

“For instance, these stretchers are built for adults,” he says in the back of EMS headquarters off the bypass, beside the jail. Traditionally, if a child was involved in a wreck while in their car seat, responders might use the seat inside the ambulance in an emergency situation.

“But that can be problematic,” he says. “Technically, if the car seat has been in a wreck, it’s not supposed to be used again.”

The solution is a simple one, yet makes all the difference in the world, he says. He affixes the stretcher with a red harness, resembling a deflated life vest with straps around it that buckle like a car seat. It is made to work on children from 10 to 100 pounds.

Walking to the head of the ambulance, just behind the driver’s seat, Rogers pulls open a seat with a built-in child seat, something the ambulances are already equipped with.

“There are so many different scenarios. The kid that’s pretty stable, that might not need a lot of treatment on the way to the hospital, we can put them here. But they have to be at least 40 pounds,” he says. But if the child is smaller and hurt more seriously, where you may have to start an IV or take care of their airway, he says, you’d want to make sure they’re on a stretcher so you can get to everything.

Bobbie Curd

Mike Rogers, a paramedic and the education coordinator for Boyle County EMS, shows the procedure for hands-only CPR on a manikin. EMS will provide free-of-charge trainings, which last about an hour, to groups who want to learn this life-saving technique.

“The main part of the accreditation is developing a plan and having someone in charge of it. We try each year to have goals in order to update things or be more proactive. Now we have more equipment to be more versatile,” he says.

The program that accredited them provided two of the harnesses; Boyle EMS purchased two more; and the agency already had one that stays in the supervisor’s vehicle.

“Pediatrics are our most vulnerable patients, so we have to be able to be more equipped. So now we have one on all of our frontline trucks. In case we have multiple pediatric patients — which would be a really bad day, but we want to be ready,” he says.

Boyle EMS has been working on the accreditation since November 2017. The work included developing a strategic plan for training, community outreach and implementation in the first year of the program. The second year, the organization comes back to the department to find out exactly what it has done and implemented before awarding them.

Part of that process also included training on how to reduce errors in administering medication to children. As of now, Boyle EMS uses the Broselow Tape. Rogers reaches into the pack on the ambulance, covered in zippers and pockets organized with different emergency treatment needs, and pulls out a long pamphlet that unfolds.

The Broselow Tape is a color-coded, length-based tape measure allowing responders to assess meds based on the child’s height and weight. It includes instructions on medication dosages, the size of equipment to use and the level of shock voltage when using a defibrillator. But they are looking at other alternatives, as well, such as the Handtevy system — a software platform now being used that he says many responders like.

“If you’re working a cardiac arrest on a child, it’s something we don’t do very often. I’ve only done three in my career,” Rogers says. He’s been a paramedic since 2000.

“For adults, we give that medication every day. For example, the dose for cardiac arrest for an adult is 1 mg; for kids, it’s .01 mg per kilogram (of the child’s weight). We can stretch this tape out from their head to toe, and it tells us where they are on the chart.”

Rogers says one of the biggest obstacles for EMS responders is the level of anxiety, and that can increase when treating children. And the only way to combat that is to be able to feel good with your skills, know your equipment and your training.

“Just this week we did pediatric life support training, which is basically criteria that lets you know what to do for a pediatric cardiac arrest — a simulation training,” he says. “That’s the only way to combat the anxiety you can have. We practice this, over and over and over and over.”

Part of his job is to recognize weaknesses in EMS and figure out what the department needs to do to improve. “We have a different goal each year. We’ve come a long way.”

The harnesses are a very simple thing, but they make a huge difference, Rogers says. As of now, he says there’s no test standard for ambulances with pediatric patients, but he says it’s coming.

“The good thing about any accreditation process is it makes you think about things you may have not before. Medicines change every day. That’s a big part of my job — to keep up with the most evidence-based medicine, best treatments and keeping certifications up to date.”

In EMS, Rogers says, they’re so used to being a reactive force.

“We can’t prevent car wrecks, so we’re sitting here, waiting to be called. This is something we can look ahead on and figure out preventive measures.”

Delivering an important message

In 2015, Boyle EMS looked specifically at chest pain patients and how to improve their care during transport.

“Many don’t realize chest pain is totally different from cardiac arrest,” Rogers says.

Through that, they received the Mission Lifeline accreditation through the American Heart Association.

“The following year, we focused on adult cardiac arrest in ‘16-’17. We wanted to increase cardiac arrest survivability, and were able to buy new monitors,” Rogers says. A good thing that came from that focus, he says, is now the 911 dispatch is doing emergency medical dispatch (EMD). “So that really helps us.”

Last year, when the EMD was being pushed for in Boyle County, Dr. Eric Guerrant said how quickly CPR is administered after a heart attack victim stops breathing has a huge impact on how likely they are to survive and how bad any brain damage might be. He said a general rule of thumb is that for every minute that CPR is not administered, a patient has a 10-percent decline in his or her chance of survival. But when CPR is being administered, the chance of survival only goes down by 3 percent every minute.

Recently, Rogers says Boyle EMS went to a church and taught a class for 6- and 7-year-olds to start them on CPR — something Rogers is passionate about.

“This year, we taught them how to check if the person is awake and what to do when calling 911,” and hopefully, they will regroup with them next year to teach them the next steps, and continue that annually.

“CPR makes all the difference in the world. If there’s ever a message we can get out, it’s learn CPR. It’s so rare for someone to do CPR before we arrive on a scene, and it’s something I’m really focused on working on. It’s just been difficult to get that message out there, and I don’t know why it’s so difficult.”

Rogers walks through headquarters into the training room, where a CPR manikin is on the table. “I’ll teach you how to do hands-only CPR, but you have to show another person,” he says. He demonstrates the steps: lightly shake them and ask, “are you OK?” then check for a pulse. Call 911 on speaker, lay the phone down and start CPR. He uses both hands on the chest of the manikin, right at the nipple line, and begins compressions.

“Sing ‘Staying Alive’ in your head and do the compressions to the beat,” he says. Further directions will be given once 911 is on the line.

“No breathing into the mouth for hands-only. This is for bystanders only. Back in the ‘80s, they wanted you to breath in their mouth, and figured that’s why people weren’t doing it.”

Boyle EMS will train groups on the CPR hands-only method free of charge. The only time they charge is if they do the full CPR course with certification, which takes four hours.

“But the basics? The hands-only we do for free — all day.”

Rogers says he always jokes around with people and tells them “ … to remember, with great power comes great responsibility. You can Google hands-only CPR on your phone and even see really funny people demonstrating it, like Will Ferrell. Or you can take this knowledge back and show people, encourage them to do it when it’s needed.”

Rogers says last year, Boyle EMS didn’t get anyone back from cardiac arrest.

“Our survivability rate was zero last year. If you look at different states, they’re around 40-50 percent,” he says, with some states championing the cause and doing great jobs at it. “For cardiac arrest, the No. 1 medicine is CPR. There’s nothing even as a paramedic I can do that’s more effective than CPR.”

He says getting the full community involved in knowing how to administer even hands-only CPR could make a huge difference.

“After you lose someone, when you know it could’ve been prevented by something like that … It’s hard when you get a 38-year-old father of three who dies. That’ll keep you motivated, when you see the family and all that, it tugs at your heart, and you say we’ve got to do better,” Rogers says. “It literally keeps us awake at night.”