In Focus: The invisible problem, one in six Ky. households struggle to afford enough food

Published 6:00 am Saturday, August 11, 2018

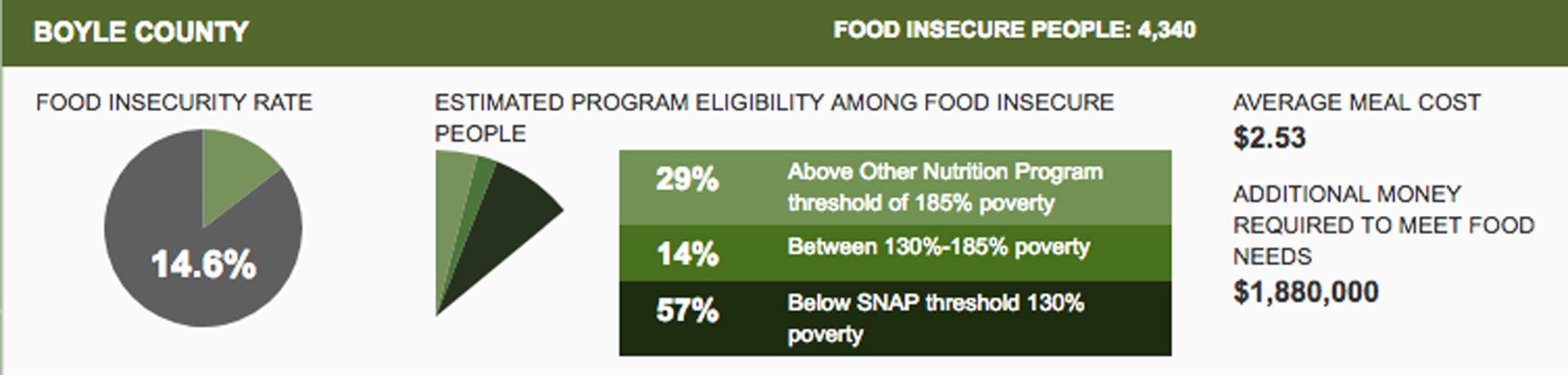

- Boyle County's food insecurity rate as mapped out by feedingamerica.org.

Despite an improving economy, more than one in six Kentucky families struggle to afford enough food — 17 percent of the state’s households, according to information recently released by the Food Research and Action Center (FRAC).

The national anti-hunger advocacy group’s newest report provides data on food hardship from 2016 to 2017.

“One in six Kentucky households being food insecure is shocking enough, but it’s actually worse in Boyle County,” says Rochelle Bayless, who runs Grace Café, a pay-what-you-can restaurant that aims to reduce food insecurity in the area.

Bobbie Curd/bcurd@amnews.com

Jennifer Earle, left and Rochelle Bayless sit in the upstairs office of Grace Café after going through the most recent stats they’ve accumulated. Earle is business manager and Bayless started the non-profit, pay-what-you-can eatery.

According to data from Feeding America’s “map the meal gap,” there were 4,340 food-insecure people in Boyle County in 2016.

Feeding America is the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. Its research says in order to solve the local hunger issue in Boyle, almost $1.9 million would be needed.

Bayless says if you research the poverty rate in Danville through the U.S. Census, “You’ll get several items pulling from the census listing the poverty rate at 19.5 percent — the national average is 14. Bottom line, Boyle County and Danville have higher food insecurity and poverty rates than the state as a whole.” Poverty and food insecurity go hand-in-hand, she says.

Most are surprised, Bayless says, to hear of how many repeat customers — many families with children — visit Grace Café daily for affordable meals

Not only are more people coming to Grace Café out of need, the restaurant is also helping more children.

Children’s meals were introduced to the menu just three weeks ago, and the cafe has already sold 235 of them.

According to Feeding America, in Kentucky, 19.2 percent of kids are food insecure, based on 2016’s stats. That’s 194,440 kids in the state.

“In January, we had 17 people who came in (to work for meals), and they continued coming back for a total of 32 meals. So far, in July, we had 36 people come in, but it totaled 99 meals,” says Jennifer Earle, the café’s business manager.

Earle says people in need are coming in up to 10 times a month to eat. If they can’t pay for their meals, they can work at the restaurant instead. Just in July, the total hours of people who worked a shift to eat was 87.

“Looking back to June, the number of hours was 36. That’s a huge jump,” Bayless says. They attribute that to feeding more families with children.

FRAC reported that Kentucky ranked 12th-worst in the nation for food hardship. It says the food hardship rate is considerably higher in households with children. At the national level, the report states after several years of decline, the food hardship rate for all households increased from 15.1 percent in 2016 to 15.7 percent in 2017. The food hardship rate for households with children is 1.3 times higher than for households without children.

Bayless says they are also seeing the gap grow between the suggested donation of a meal and what people are actually paying. She thinks this is due to a couple of different trends.

“That’s really showing the pay-what-you-can model in action: More people are truly only paying what they can,” Bayless says. However, she thinks people also are living under the “scarcity mentality.”

“The old saying ‘your eyes are bigger than your stomach,’ and you’re ordering more food,” she says — if you haven’t eaten all day, you’re more apt to order a larger portion.

Many still continue to be surprised by these trends. “I was told every single day, ‘We don’t have that problem in Boyle or Danville; there’s no homeless or poor people here.’ I can tell you there is a huge poverty problem in Danville and Boyle County. It’s invisible.”

Bobbie Curd/bcurd@amnews.com

Grace Café has signs as you enter, explaining how the hunger charity works. Sitting on the counter to the left is the birdhouse, an anonymous system patrons may use to pay by.

Sure, Bayless says — we don’t have the stereotypical people you see in bigger cities, panhandling on Main Street. But what about the people “living on the margin,” who are living out of their cars in parks or the Walmart parking lot, or couch-surfing with friends.

And many others are average, everyday families who are trying to make ends meet, figuring out how they are going to feed their family. “That’s what I see the most of,” Bayless says.

“Food hardship affects people in every community in Kentucky, although it often goes unseen by those not looking for it,” says Kate McDonald, KY Kids Eat Coordinator at the Kentucky Association of Food Banks. “Hunger can hide behind doors of nice houses with mortgages in default, with all of the income going to housing costs, leaving little or no money for food. Sometimes it hides behind the stoic faces of parents who skip meals to protect their children from hunger.”

On Tuesday, Bayless had 12 people working in the café for their meal, along with four children. They’ve even had to limit shifts to 30 minutes each, because they’ve had so many come in to work for food. As of now, they only have enough funding to be open for one meal a day, but she says if they were able, they’d probably keep a full house if they served three meals a day.

“We’re only halfway through the year, and already we’ve broken every single record,” Bayless says. The fact their client base is increasing is actually good news on some level, “because we’re meeting our mission. But it certainly puts more pressure on fundraising to make sure we meet the budget.”

Grace Café takes donations on its website. However, Bayless and Earle both say they remind the public the café is a farm-to-table restaurant.

“Sure, we’re a hunger charity … But we’re also in the bounty of the season right now … We buy local as much as possible, working with 20-30 farmers throughout our season,” Bayless says. “The freshest local food is on our menu right now. Just come eat here, and maybe you’ll want to pay-it-forward and help.”

Walking in different shoes

Nikki Byrd-Orcutt first went to Grace Café for her 16th birthday in March. Her paw-paw had bought her birthday cake mix and a friend bought the icing, but they wanted to go somewhere as a family.

“We didn’t have the money to take Nikki anywhere to eat for her birthday, so her friend said we should go there,” mom Valarie Orcutt says. She’s also mom to Julie, 18. They sit on the couch together inside of their Toombs Court home, a government housing area of Danville. The yard and porch are pristeen, with flowers, a few porch decorations and chairs. Believe it or not, Valarie says, everything inside their home — with exception of the TV — was free.

“You do what you have to. You can get on Facebook, people are always giving things away …” and through the Salvation Army, she says. They pay $820 a month to live in the three-bedroom apartment, and are responsible for part of their electric, which usually runs about $100-$140.

Bobbie Curd/bcurd@amnews.com

Valarie Orcutt, right, poses with her daughters, Julie, from left, and Nikki Byrd-Orcutt inside their Toombs Court home. The family has been through a lot over the last few years, including a year and a half stint where they lived out of their truck.

The family is from Danville, but were living in a trailer in Stanford. Valarie became very ill, but didn’t want to go to the doctor; she was afraid of what she’d find out. She had already been treated for breast cancer with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation.

“I didn’t want to go into the hospital, I knew there would be nobody to pay our bills and I didn’t want to lose our home.”

But her daughters finally made her go by calling an ambulance. She was then diagnosed with ovarian cancer and had to go through four more surgeries. Medical professionals told them Valarie would have died soon if the girls hadn’t gotten her to the hospital.

Ultimately, her fears became a reality. The family lost their trailer and everything in it. The girls would sometimes spend the night with her in the hospital room and take showers there before school. Sometimes, they’d stay with an aunt who has a one-bedroom apartment or with friends. Sometimes they’d eat, if the friends had enough to share. Sometimes they didn’t eat.

After Valarie got out of the hospital, they stayed with a family member, but things didn’t work out so well, and they were put back out on the street — one of the most difficult times in her life as a mother, Valarie says. Throughout the late fall and winter months, they lived out of their truck, until they were accepted into public housing in December.

“We were homeless for about a year and a half,” Julie says.

They would park in the Walmart parking lot, or down some country road. They spent a lot of money on gas keeping the truck warm.

Valarie says, “I mean, some people are selfish. Someone can say they’re hungry …”

“Some are like ‘well, why don’t you go get a job and provide for yourself,’” Nikki says.

“I didn’t want to be rude, but yeah. That’s what they say to you,” Valarie says. “But they don’t know. They can talk about people all they want, but they’ve never walked in someone else’s shoes, or been through what you’ve been through.”

People can be real stingy, Valarie says. If you need something to eat or drink, they may not give it to you.

“Before Grace’s, before that, we just wouldn’t eat sometimes. If you knock on my door for a glass of water, I may not let you in my house, but I’ll give you a glass of water,” Valarie says.

But they haven’t found those attitudes at the café, they say. They’ve met people who have become friends, too.

“If there’s extra seats when we’re there, we let someone else sit down with us,” Nikki says. She says she can tell some people are embarrassed to ask for help. “But they don’t judge you there.”

Valarie says if you only have a dollar to pay for your meal, you can use the birdhouse — an anonymous pay system Grace Café uses — “And people around you don’t know.”

“We go back a lot as a family. It’s a good, friendly place. A good environment,” she says. “It’s homey and they don’t exclude you if you can’t pay.”