‘She took a part of us with her’ Suicide from a mother’s perspective

Published 6:23 am Saturday, September 15, 2018

- Photo contributed Catheryne Claunch committed suicide on June 4, 2017. Her mother is working to help prevent others from choosing that path.

On June 4, 2017, Catheryne Claunch sent a private message to someone on Facebook, trying to find a gun for what she said was a fun outing with friends to a shooting range. That was at noon; by 1:30 p.m., she had the gun, which she purchased for $180. She pulled into a dollar-store parking lot in Perryville, then pulled the trigger.

She was 20 years old.

Chris Claunch says no parent ever expects to get “that phone call.”

Photo contributed

Todd and Chris Claunch, left and right, stand with their daughter, Catheryne, at her high school graduation.

For many, National Suicide Prevention Week may not mean anything. To Chris, it literally means the difference between life and death. As the week was observed Sept.10-15 with organizations distributing literature, statistics and hotline numbers in the hopes of getting support to the right people, Chris continued her work as a volunteer to hopefully save a life.

It’s something she says she wasn’t able to do for her own child.

“For many of us, the thought of someone we love committing suicide never crosses our mind. They take a part of us with them.”

…

Catheryne had a good childhood. She grew up in a gym because all of her brothers and sisters played sports. “School, church, gym and sports was our routine,” Chris said.

Then, she got pregnant and missed her junior year of high school. Chris went to part-time so she could spend more time with Catheryne at home; she took her out of school because she was getting bullied. Her husband left his job to take care of the baby so Catheryne could return and finish her senior year. She became an integral part of her varsity basketball team at Mercer County High School, with her ‘14-’15 year stats outpacing national averages.

One of Catheryne’s old coaches offered her a scholarship to Berea College. Chris stayed with her there to take care of the baby while she practiced basketball in the evenings. Eventually, Catheryne left to come back to Harrodsburg.

Right away, after Catheryne’s death, Chris’ first thought was, “I’ve helped so many people get through mental health issues, referring them to counseling. How could I have not been able to help my own daughter. How could I not see this?”

Chris lives in Danville and works for Mercer County Schools with English as a Second Language students, and had already been doing work with Stacy Blacketer’s Medical Reserve Corps group through the health department in Mercer for about five years. Since she’s bilingual, she was on the list to help out in the case of any emergencies in the area.

With a strong Christian faith, she also remembers how — even before this happened — she was thinking about her kids in all scenarios, as most parents do. She and Todd Claunch have four children, and Chris recalls thinking, “If something happened to me, to us, tomorrow, we’ve done everything we could to help our children.”

“I also believe everyone comes into this world good — as a good person. It’s the experiences in your life that lead to the outcome. But suicide doesn’t discriminate.”

Someone had wrecked Catheryne’s vehicle, so she had no way to get around. Relationships in her life weren’t what she wanted them to be. She lost her job. And she was hanging out with the wrong crowd. Then, an even worse crowd.

“Some of my friends said, for Catheryne, it really was just the perfect storm. Looking back, now I see they’re right.”

Chris Claunch poses with her daughter Catheryne. Chris says her daughter had a very happy childhood.

…

A couple months after Catheryne died, Chris got an email from Stacy about a suicide prevention training — called QPR (question, persuade and refer) offered in Richmond. “A little too late, but I dragged my husband over there with me. I was trying to find answers.”

As she sat through the training, she realized as children get older, they’re not at home as much. Their friends will be the ones to see the real differences in them, the changes.

“I went back to Stacy, and I said we need to do this with school kids. Their friends will know what’s going on with them …” even more than their parents, usually, Chris says. “Our school does an excellent job as far as identifying and getting students help; my concern is once they leave school, they don’t have that support. A lot of people become lost.”

Chris has received multiple messages on social media from girls asking her what they should do if they know someone who has expressed thoughts about suicide. She heard stories about parents catching their kids in the act.

“That’s part of the QPR training, trying to help individuals understand and be up front, when they see someone in trouble, if they even have an inkling, to question them, prevent them from harming themselves and referring them.”

Chris says more than half of people who take their own lives are not diagnosed with any type of mental illness; it’s simply not being able to cope with what’s going on. “They just go through the perfect storm and can’t see their way out.”

After her daughter took her own life, Chris dug into her social media accounts and found more harassing messages. She also did her own research on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website.

“When I go to the CDC site and see all the stats, that’s where I see it now. I’m like, holy crap, she was going through all of that.” She says before Catheryne committed suicide, as her mother, she never had it on the radar at all. Maybe because she hadn’t seen the stats.

Chris said her other kids have told her “we got through (things like that), why can’t she get through it?”

“But we understand now your life can become so dark that you don’t see a way out,” she said. “Something that could be so simple to you and I — ‘oh, we’ll just get another job,’ or ‘we’ll make it on our own without our relationships.’ Some can’t see it that way. A lot of these younger people have had life a little bit easier, and when times get tough, it’s hard to get through it — the coping skills just aren’t there.”

…

Throughout her volunteerism, she’s listened to people who contemplate doing the same thing — they don’t see a way out, they don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.

“And I keep telling them to stay strong, it will get better.” But, she says there are those individuals who never speak up and never say anything. And, unfortunately, she says lots of small cities and towns don’t want to talk about the problem. But the suicide rate continues to climb, she says — so, we’re not handling this right.

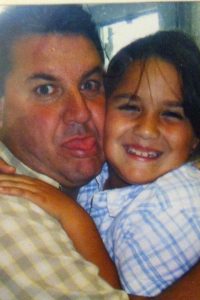

Todd Claunch and his daughter Catheryne hug for a picture

“We’ve tried keeping quiet about it, not talking about it, and that’s not working. So I’m hoping through the trainings with Kathy Miles, we can get sources of strength in the schools that we can give those kids, and give them the skills they need in order to see that it’s OK — you can get through this and there is help.”

Chris constantly posts numbers for people to call in order to get help on social media. She’s gone to their homes to be with them while they’ve called. “Maybe because we’d hoped someone would have done that for our daughter, is why I do it.”

She recalls one specific person during Catheryne’s funeral who admitted she had thought about suicide. “But after what she saw us go through, she said she could never do it. She said she’d never put her parents through what she saw us go through.”

Now, just a little over a year later, Chris still cries when she talks about her daughter. Her family goes through the grief in waves. It is still hard to talk about, but she says after talking to her husband, “I figured our story would make a difference. Hopefully.”