Plans for $87M grant shared at opioid roundtable

Published 6:49 pm Thursday, August 29, 2019

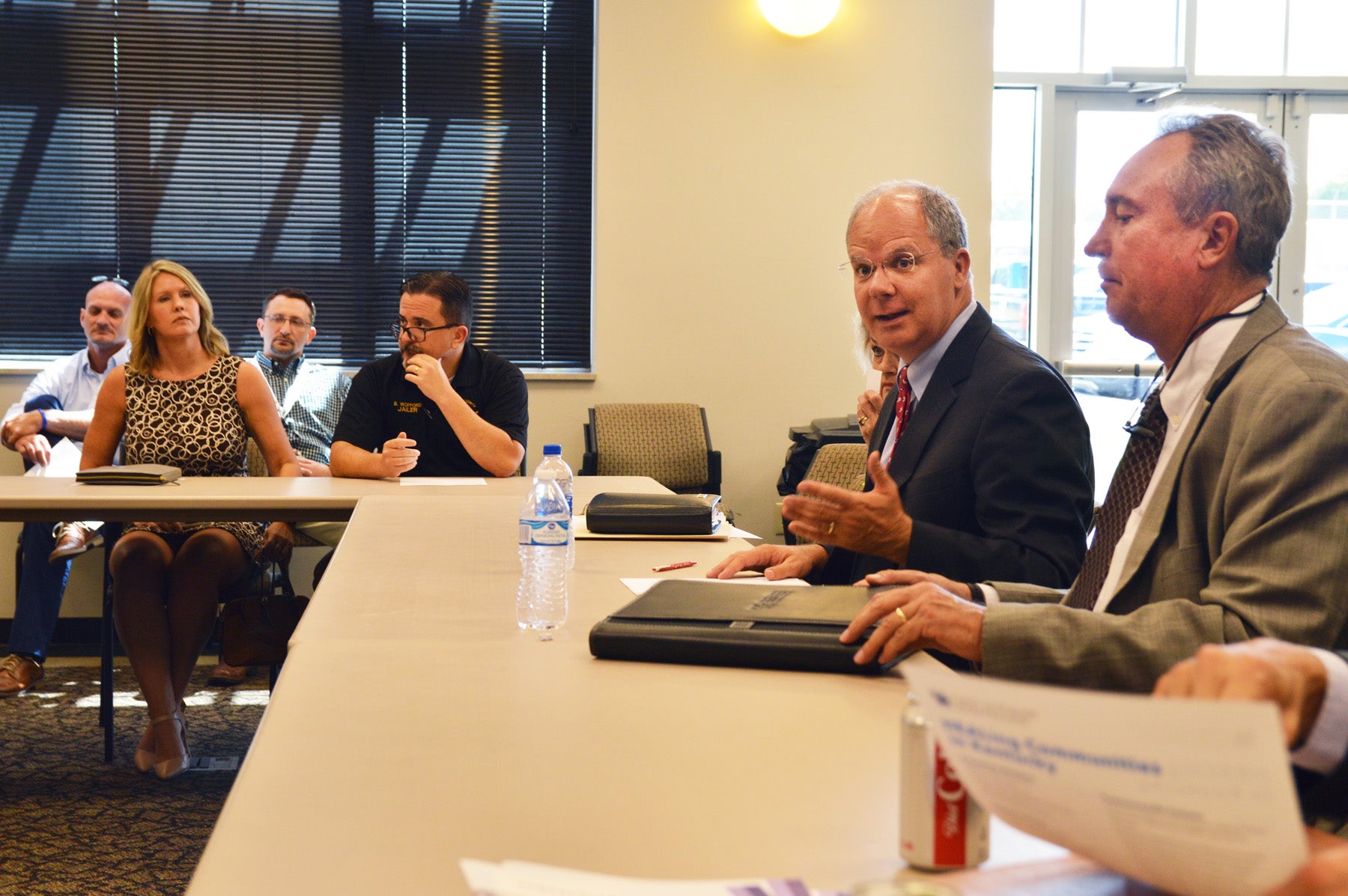

- Rep. Brett Guthrie talks to participants during Wednesday's roundtable on the opioid crisis in Danville. (Photo by Bobbie Curd)

Boyle is one of 16 Kentucky counties chosen to be part of an $87 million study through the University of Kentucky, researching and implementing community intervention tactics to battle the opioid epidemic. The study will focus on how to implement best practices in health care, behavioral health and jail environments, with the goal of reducing opioid-related overdose deaths by 40% over three years.

The next steps of the study were explained during Wednesday’s opioid roundtable discussion held in Danville with Congressman Brett Guthrie, the Republican representative for Kentucky’s Second District. Guthrie authored the Comprehensive Opioid Recovery Centers Act, passed last year, and held a roundtable discussion in Danville last October.

Wednesday’s discussion included more than 30 participants, including representatives from care providers, like Isaiah and Shepherd’s houses, Ephraim McDowell Regional Medical Center and others; research experts from UK and Western Kentucky University; and federal, state and local officials.

Why Boyle was chosen

Dr. Hilary Surratt, associate professor with the University of Kentucky College of Medicine, presents the plan through the Center on Drug and Alcohol Research, called HEALing Communities in Kentucky, for how grant money will be used to research and treat addiction issues. (Photo by Bobbie Curd)

The HEALing Communities Study (Helping to End Addiction Long-term), a four-year cooperative agreement and the largest grant UK has ever received, was awarded to the university’s Center on Drug and Alcohol Research. Dr. Hilary Surratt, associate professor with UK College of Medicine, explained the grant was awarded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institutes on Health and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The study will be assisted by 14 commonwealth partners, including the Agency for Substance Abuse Policy, Cabinet for Health and Family Services, the Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, local Agency for Substance Abuse Policy boards (ASAP), and local and district health departments.

Surratt said UK was one of four institutions funded to participate in the partnership; the others are Ohio State University, Boston Medical Center and Columbia University. UK’s team is made up of 19 researchers from six colleges, including medicine, public health, nursing and pharmacy, but the work will include 100 researchers, staff and state community partners.

Boyle was chosen out of the state’s 120 counties using a systematic approach, and Surratt explained how the list was narrowed down to 16:

• 48 counties had 25 or more opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 people in 2017;

• 35 of those counties had five or more overdose deaths;

• 28 have needed justice infrastructure;

• 19 have needed public health infrastructure; and

• 16 counties were are not already involved in major UK intervention projects.

Surratt said, “I’ll have to be honest — I’ve had calls from counties, and it’s a bit heart-breaking … they ask, ‘Why weren’t we included?’ You have to have those tough conversations, and just be transparent and tell them how we went about choosing them.”

She said the aim is to collaborate with state and community partners to implement evidence-based interventions to save lives, help people receive recovery support services and inform the nation on what strategies will help heal from the opioid crisis.

Embedded ‘Care Teams’

Surratt said a number of strategies are being undertaken in order to reach a 40% decline in opioid-related deaths over three years. “We’re increasing access to naloxone, increasing distribution. We are trying to link people to treatments and actually work on retaining people in treatment, which is a big problem because there’s a lot of drop-outs. And also better utilize recovery support services, so those are major strategies we’re implementing here,” she said, adding that’s in addition to what Executive Director Van Ingram’s Office of Drug Control Policy is doing.

“One of the things that’s most exciting to me, because I do a lot of community-based research, is the level of engagement that we will have in each of our 16 counties,” Surratt said. Across the four states, 67 counties will be studied. Surratt feels it will result in a “broad public health impact,” because there is a balance of rural and urban areas.

Surratt said UK was funded in April, and they are hopeful they will actually get to implementation by December. She offered what that will look like with embedded “Care Teams” in each county. They will consist of a community coordinator overseeing the initiative, with the help of the local ASAP board; a syringe services program specialist, most likely to be placed at Boyle County Health Department; a treatment care navigator; a jail care navigator; and a probation and parole prevention specialist. She said their hope is to have these positions filled by local people already in the community.

She said with the large amount backing it, “this is a really well-resourced study … We’re able to actually resource interventions … provide additional personnel in a health department … we can purchase naloxone, we can do the things that need to be done, but we have to look at it with an eye towards sustainability, also.” She said a team of health economists are also involved, in order to track data and explain the costs to implement initiatives in other communities.

Surratt said she was grateful to have such positive responses and support from health department directors, such as Brent Blevins, who was also present — support she said was critical to getting the plans for the research initiative in place.

She also said local ASAP boards have been instrumental in the approach, due to how well-respected they are in communities. Kathy Miles, coordinator for Boyle County ASAP, was also at the meeting.

“We are extremely lucky to have the ASAPs in place,” Ingram said. “It gave us such a leg up over some of the other states, because we already had community groups to work with. Some of the other states had to scramble and send somebody from Columbia University into some county in New York that they’d never been in before, and try to figure out, ‘How do I engage local people on these issues?’”

“We will really invest in working with communities, and in particular our ASAP boards are heavily involved in guiding us through implementation of interventions in each of our counties, as well as our health department partners, our criminal justice partners …” Surratt said.

Boyle County Jailer Brian Wofford asked Surratt how she saw the “jail care navigator” being implemented.

She said one of the strongest pieces of evidence in overdose rates is the fact that those who have been incarcerated lose their tolerance and are at a high risk of overdosing when they reenter the community. Surratt said the idea of the jail care person is two-fold: simple overdose education paired with Naloxone distribution is one, but also linking people up with treatment on their way out.

Wofford asked if this means someone from the Care Team will be at the jail Monday-Friday. Surratt said the plan is still evolving, and it’s not certain yet what that looks like for criminal justice systems. “We are thinking around those logistical issues.”

News releases and updates regarding the HEALing study can be found at uky.edu/healingstudy.

Watch for another story soon on what’s being done by the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy to battle the opioid epidemic and how it will help locally.