Sgt. Sampson survives japanese captivity

Published 9:58 am Sunday, July 12, 2020

(Editor’s note: This is the second part of a two-part article that continues the story of Ernest L. Sampson, a former Harrodsburg Tanker, who survived Japanese captivity during World War II. Information was provided by 1st Lt. Cody Stagner, Kentucky National Guard Public Affairs, and photos were made by National Guard Sgt. Jeffrey Reno.)

By BRENDA S. EDWARDS

Contributing writer

Sgt. Ernest L. Sampson Jr. signed to fulfill a one-year term of military service in the Kentucky Army National Guard in 1940.

Sgt. Ernest L. Sampson Jr. signed to fulfill a one-year term of military service in the Kentucky Army National Guard in 1940.

In 1940, the 38th Tank Company, better known as the Harrodsburg Tankers, was called to federal service and was re-designated as Company D, 192nd Tank Battalion.

Prior to the United States entering the Second World War, the 192nd Tank Battalion proved superior among other armor units during large training maneuvers at Camp Polk, Louisiana.

General George S. Patton, while observing their training in 1941, said in regards to their performance, the only way to get a tank company to function is have them all be country boys from the same home town.

After these country boys certified their skills during large-scale training operations in Louisiana, the Kentuckians immediately had their bonds in brotherhood put to a test in battle and survival on the world stage.

In late October 1941, Pvt. Sampson and the Harrodsburg Tankers boarded a ship and set sail to the Philippines Islands, where they were expected to take part in Operation PLUM (Philippines, Luzon, Manila) along with the 194th Tank Battalion.

Assigned to Ft. Stotsenburg, on the Bataan Peninsula of Luzon Island, they awaited maneuvers with the 194th by enjoying the leisures of island life. Many enjoyed bowling, movies and swimming or outdoor football, badminton, horseshoes, or threw a football around.

Fun ends

Following suspicious enemy activity in the China Sea shortly after their arrival, the 192nd was ordered to guard Clark Field at Clark Air Base. The Philippine Air Force base was connected to Ft. Stotsenburg, and allowed Allied Forces to run bombing and reconnaissance missions in the China Sea.

On Dec. 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor, located in Oahu, Hawaii, became the target of savage airstrikes carried out by Japanese warplanes.

Only hours after Pearl Harbor was attacked, the onslaught of bombing raids echoed 5,000 miles west at Clark Air Base where the Harrodsburg Tankers, an armored unit trained in tank-on-tank combat, could do very little against the swarms of planes flying overhead.

They watched in horror and disbelief as hundreds of Japanese bombers rained down munitions on Allied targets caught resting and refueling at Clark Field.

Pvt. Robert H. Brooks, a fellow Kentuckian and active duty soldier assigned to their unit after it was federally activated, was the first armor casualty of the war. A parade field at Ft. Knox was renamed in his honor. Brooks Field is still in use today.

Other Tankers, including Sampson, regrouped after the raid and continued the battle alongside Filipinos at the Battle of Bataan from Jan. 7-April 9, 1941.

After the surrender of Allied Troops at the Bataan, Sampson and a few other members in his company decided they were not yet ready to raise the white flag, according to Jim Opolony, website, bataanproject.com.

In the middle of the first night of surrender, they split from the group and made their way to the southern coast of the Bataan Peninsula. Sampson and his comrades found a boat, held the owner at gunpoint, and forced him to drive toward Corregidor Island at the entrance of Manila Bay. It was a naturally fortified island that held the remaining strongpoint of Allied Forces in the Philippines.

Unfortunately, the Japanese forces caught up to Sampson, again. Assigned to an anti-aircraft weapon, Sampson valiantly fought against the Japanese, one last time, at the Battle of Corregidor, May 5-6, 1942.

With no reinforcements and nowhere left to run, Sampson joined more than 60,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war taken captive by the Imperial Army and taken to prison camps.

Sampson, taken prisoner at Corregidor, waited two weeks for the barge ride off the small island.

Other Tankers who surrendered during the fall of Bataan were already on their way, but in a more enduring manner.

The other group of Tankers began captivity while being forced-marched from Mariveles, near the southern tip of the Bataan, to a train station in San Fernando, where they boarded boxcars for transport to the nearest holding camp, Camp O’Donnell.

The unit survived

All Kentuckians survived the 63-mile walk to San Fernando, while more than 2,500 Filipinos and 500 other Americans died in the Bataan Death March.

Prisoners on the march lost their lives due to dehydration, starvation, infection, disease, and brutal physical abuse from their murderous captors.

Sampson’s trip to his camp was arguably less brutal. They started by sea, taking a barge to Manila, but the barge stopped 100 yards from shore and captives were forced to swim the rest of the way.

Sampson marched through Manila to Bilibid Prison before transfer to Cabanatuan, a camp being run by the prisoners of war held captive there.

He stayed at Camp Cabanatuan for two years in overcrowded barracks, sleeping on bamboo slats without mattresses, bedding or mosquito netting.

The work detail consisted of cutting wood for the kitchens, farming in the rice patties, and working in the airfield.

Sampson was a skilled mechanic and was eventually selected to work at the airfield.

Aside from the occasional bread and a rarity of vegetables, wet rice was the main food for these prisoners.

Overflowing with Allied Troops, the Japanese captors lacked the means to properly and safely feed them, escort them, or house them.

Ten Tankers died at Cabanatuan and another two died at the small camp on the Palawan island. Three others lost their lives at Camp O’Donnell.

Ten more tankers did not survive a transfer from the Philippines to Japan aboard the various freighters used as transport carriers.

Due to the high mortality rate of their human cargo, the Japanese freighters called “war ships” were used to transport prisoners of World War II.

On July 17, 1944, Sampson was taken with more than 1,500 prisoners to the port at Manila where he boarded the Nissyo Maru, a Japanese hell ship headed to mainland Japan.

Conditions horrible

The ship remained in the baking sun at Manila Bay for seven days before departing. Temperatures in the holding area were estimated to consistently remain at more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

As part of a convoy with other Japanese ships, the Nissyo Maru and other ships fell subject to targeting by American submarines. Several lives were lost at sea.

On Aug. 3, 1944, the freighter and its cargo arrived at Moji, Japan.

Sampson was offloaded and assigned to Camp Narumi #2-B (a.k.a. Nagoya #2), where he bunked with three other men, sleeping on straw mats and pillows made of canvas and stuffed with corn husks.

As common punishment to their captives, the Japanese beat them with sticks, clubs or rifle butts. They also made them stand out in the cold at the position of attention for long periods of time while being denied water, food, or even clothing.

The main purpose for this camp was to provide a labor force at the Nippon Wheel Manufacturing Company in Nagoya. Sampson worked six to eight hours each day and rode train cars to the factory with Japanese civilians.

One of their greatest past-times was talking with others about food. Survivors claimed the act of speaking about specific meals together somehow freed their hunger, momentarily, as if they had just eaten, according to BataanProject.com.

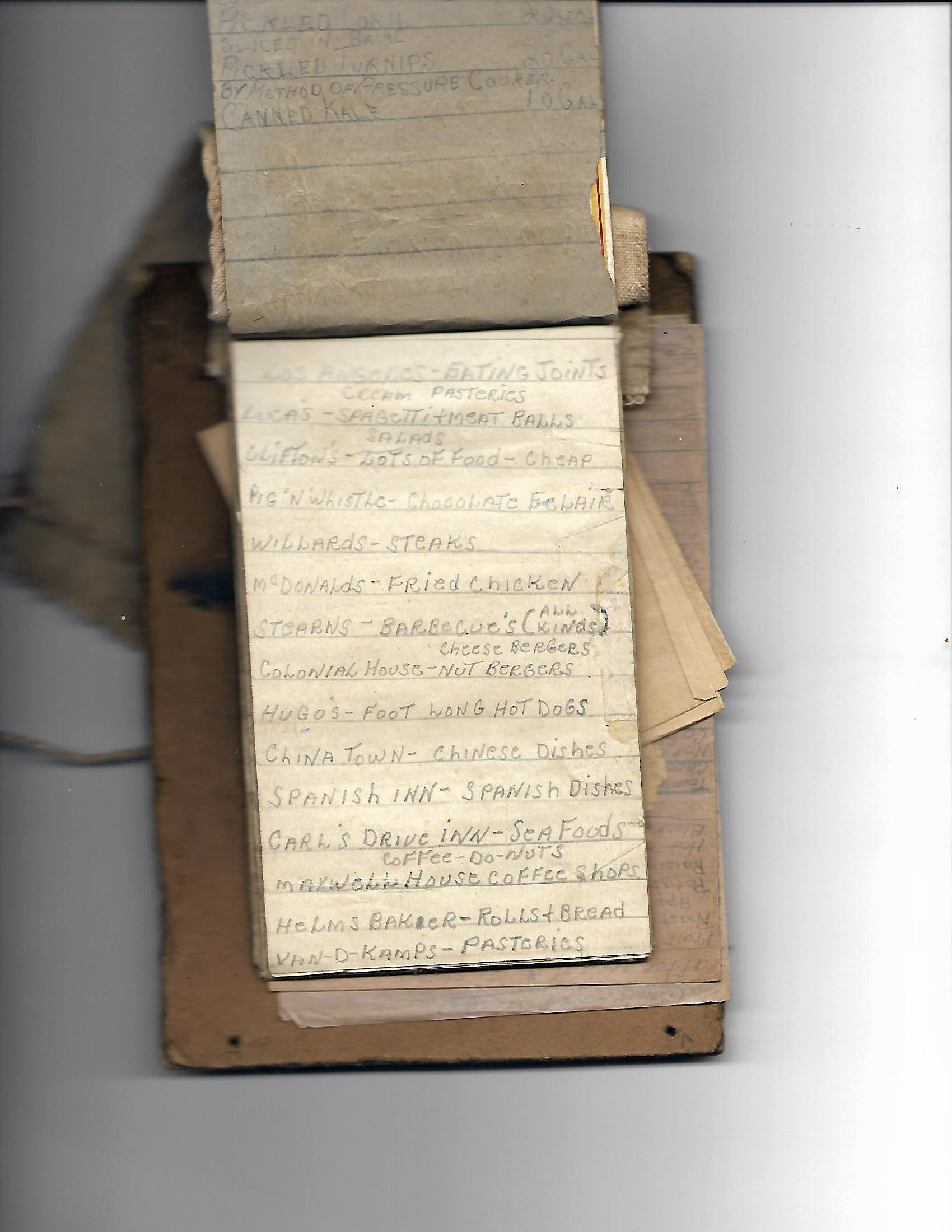

Sampson’s journal, the most interesting artifact recovered by Andrew Bryant, possibly corroborates this claim. The majority of handwritten pages involve food as he lists various recipes and wrote page after page detailing how to create the perfect hearty meal when he returned home.

Sampson’s journal, the most interesting artifact recovered by Andrew Bryant, possibly corroborates this claim. The majority of handwritten pages involve food as he lists various recipes and wrote page after page detailing how to create the perfect hearty meal when he returned home.

As the war waged on, Allied Forces reigned victorious in Europe and pushed into Japan, calling for their surrender.

In early August 1945, continuous unanswered requests to lay down their arms prompted the dropping of two atomic bombs by Americans on Japanese soil — first on Hiroshima, then Nagasaki.

On Aug. 15, prisoners of war heard the emperor speak to his people over a live radio broadcast. Interpreters translated to the Americans how the Japanese emperor had surrendered his Army.

The Japanese delegation officially surrendered September 2, 1945.

Meanwhile, Sampson’s life at Camp Narumi flipped upside down as the tables turned to his favor.

Guards abandoned their posts at camp, and B-29s dropped fifty-gallon barrels of supplies to the former prisoners of war.

Returns to U.S.

Sampson accepted short-term residence at the camp with the others. They secured their own perimeter with rifles left behind by the guards. They ate whatever food they had left, and what was dropped out of the sky by the Red Cross. He and other prisoners collected 8,000 Yen and bought a local Japanese working bull. They ate real beef from the 1,400-pound bull for six meals, without rationing, while waiting for a ride home.

On Sept. 12, 1945, they were escorted by American Troops to southern Japan, where they received medical treatment aboard the U.S.S. Rescue.

Sampson returned to the Philippines for additional medical treatment before setting sail for the U.S., arriving at Seattle Washington on Oct. 9, 1945.

It took several months before the Army released Sampson. Recovery was slow after enduring such poor conditions while in captivity.

Pvt. Sampson was promoted to the rank of sergeant and released to his home in Harrodsburg, before his discharge on April 8, 1946.

He lived through Japanese air raids, the Battle of Bataan, the Battle of Corregidor, the Bataan Death March, Japanese hell ships and numerous prison camps. He endured more than 1,200 days at the hands of a brutal enemy.

His perseverance, strength, honor and personal courage is matched by very few. He is a true local hero of the Kentucky Army National Guard.

Only 37 of the 66 Harrodsburg Tankers taken prisoner of war survived this tragic tale from World War II.

Sampson fathered two sons with his wife, Sadie McRay, and lived out his remaining days on his farm in Mercer County.

He died Dec. 1, 2001, and is buried at Spring Hill Cemetery in Harrodsburg.

A tank, on display in Harrodsburg, memorializes the Harrodsburg Tankers, who endured capture and placement in prisoner of war camps by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.