Tools of the trade

Dispatch, equipment key parts of police officers’ work

Published 9:22 am Friday, August 28, 2020

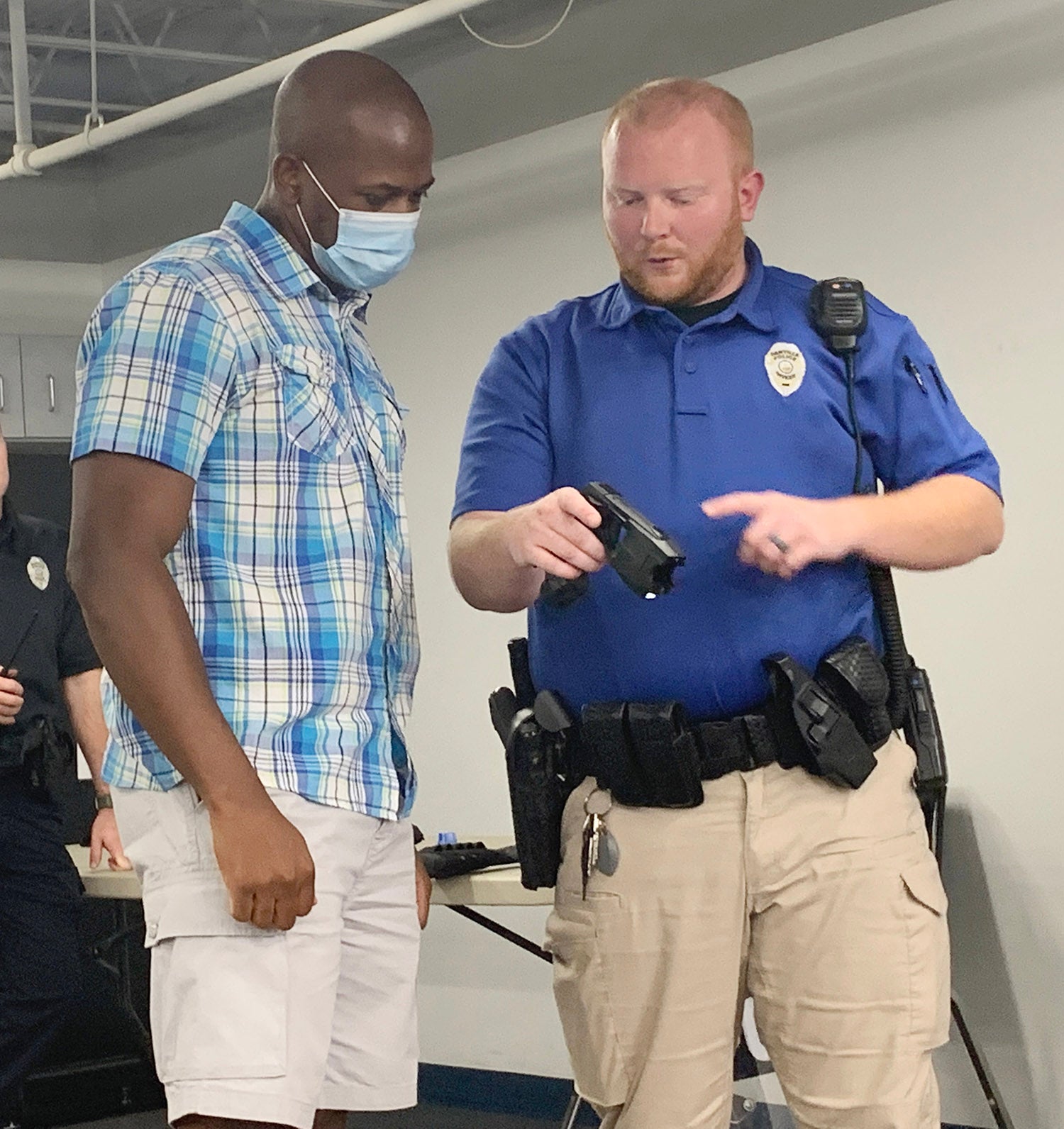

- Officer Adam Wilson demonstrates the equipment used by Danville Police officers during Tuesday’s Danville Police Citizens Academy class. (Jeff Moreland photo)

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles written to share the experience of members of the current Danville Police Citizens Police Academy. The 10-week academy will teach the members about all aspects of local police work.

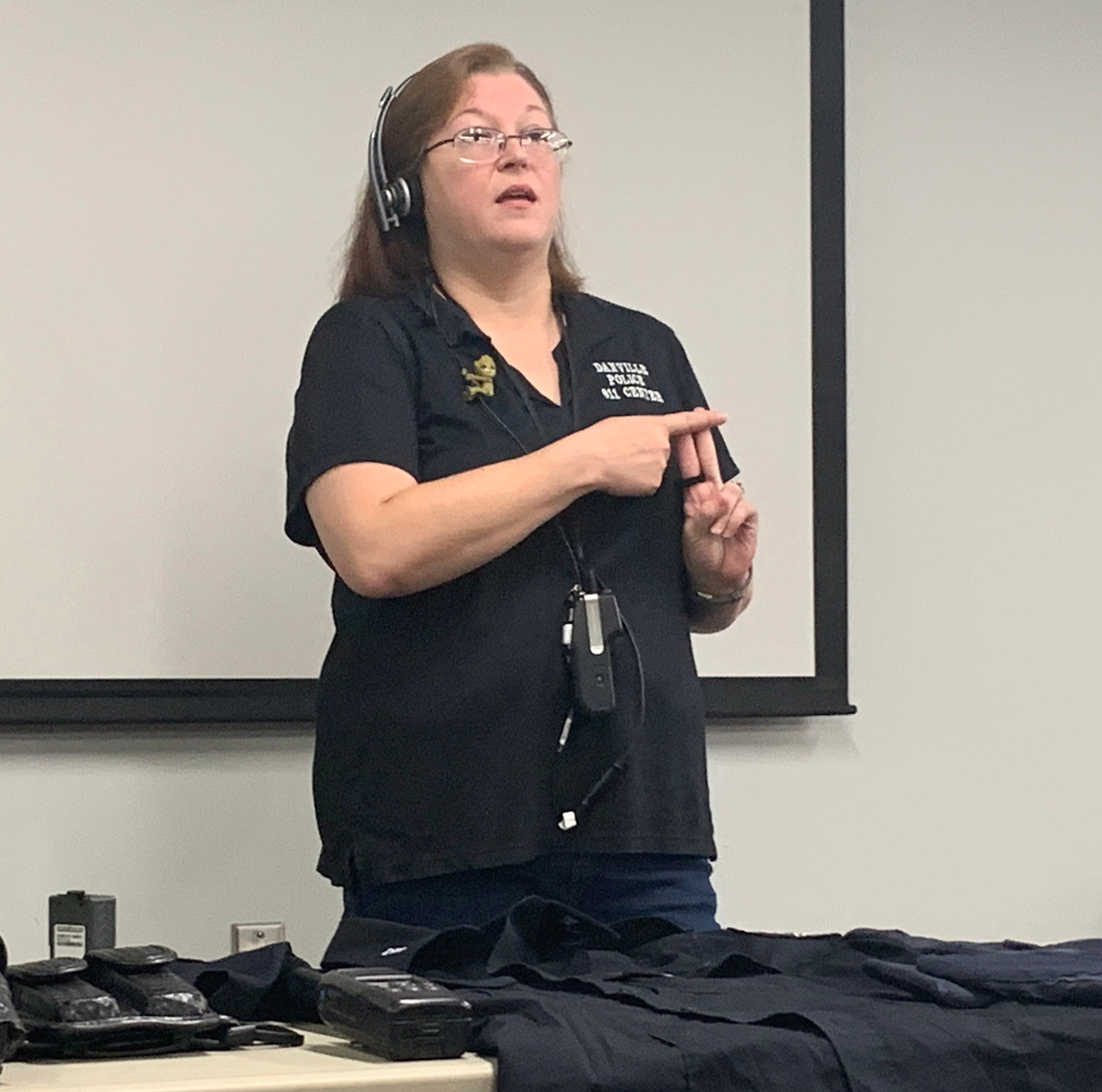

Melinda Ennis, assistant director of the Boyle County Dispatch Center, speaks to members of the Danville Police Citizens Police Academy class Tuesday night. (Jeff Moreland photo)

Police officers can’t do their jobs without a lot of support, and much of that comes from professionals working in the 911 dispatch center.

Melinda Ennis, assistant director of the Boyle County Dispatch Center, spoke to members of the Danville Police Citizens Police Academy class about the duties of dispatchers and how they coordinate police and other local emergency responders to the places where they are needed in Boyle County. And as she explained, they not only dispatch Danville Police, but many other agencies within the county.

“We handle everything from the police department. They are the busiest agency we deal with, but we also have to think ‘big box,’” she said. “Just one call for the police department can also involve all of the other agencies we have – the sheriff’s department, Junction City Police Department, Perryville Police, Boyle County Fire Department, Boyle County EMS, Junction City Fire Department, Perryville Fire Department, as you see, it grows. So we don’t just handle one type of call.”

Being a dispatcher can make for some very busy days. Ennis said one accident can generate up to 40 calls, and sometimes those calls come in with as few as two dispatchers on duty to handle them all.

“Cell phones are a big bonus, but also in a way are a hindrance. Everybody wants to help, but then again, we’re getting 40 phone calls at the same time. It has its pros and cons,” she said, adding that the calls usually don’t stop until people hear sirens and realize help is on the way.

The dispatch center averages about 30,000 calls per year, and Ennis said they are already at 19,900 calls, “and it’s only August,” she added.

All of those calls are not actual emergencies. Ennis said she read a recent report that approximately 70% of all 911 calls are accidental calls, or pocket dials.

“We send an officer if we have a location, or we will call them back if the telephone number shows up,” she said.

Assistant Police Chief Glenn Doan said officers always go in response because you never know if there is an actual emergency. He said officers have arrived on scenes to find actual emergencies, but they have also responded to find someone working on their job or mowing their lawn, completely unaware they had dialed 911.

Ennis said features on most cell phones now allow a person to press either the top button on their phone, or some other button, to automatically dial 911. She said this is a feature to help dial the number more quickly during an emergency, but it often provides the errant calls.

“That’s a program on phones we can’t disable and we should never disable, but if you push the start button or the top button three times, it will automatically call 911. It can save lives. So even the one phone call that saves that life is worth the hundred others that we had to go through,” she said.

Other false calls are made when people give an old phone, one that no longer has an active cellular service, to a child to allow them play games installed on the phone. Ennis said even a phone without service is capable of dialing 911, and people should be aware of this before giving a phone to a small child.

The dispatch center currently has one part-time and 11 full-time dispatchers, and that still leaves them short staffed. She said the center could use at least two more dispatchers. For scheduling, the center tries to have four people on day shift, four people on second shift, and three people on night shift, which runs from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. She said it sounds like a lot of people working at one time, but things happen where they are extremely busy, and at other times, illnesses can cause the center to have fewer people on duty than what would be the ideal situation.

Ennis said the calls fluctuate with the seasons, with more calls coming during the summer when the weather is good and people are out, as well as during times like the Christmas season, when there are more vehicle break-ins and thefts.

A new dispatcher will start off at the center earning $12 per hour. When she started nearly 16 years ago, Ennis said that rate was $10.25 per hour.

Training is a huge part of the job, and after a potential new dispatcher makes their way through all of the steps, which include a background check, suitability testing, polygraph testing and more, they will attend a four-week academy at the Department of Criminal Justice Training Center in Richmond.

“That doesn’t include the training program we have in house,” Ennis explained. “Ours is one of the most extensive training programs around. We’ve actually had other agencies ask us for parts of our training program. So we don’t just put them on the phone and say, ‘Go for it!’”

A new dispatcher will first handle phone calls, then learn about the paperwork involved with the job, followed by being on the radio. Ennis said this is done to put all of the skills together and build a basis for the dispatchers.

“I’ve been here almost 16 years and there will still be a call where I’m thinking, ‘I’ve never had this before,’” she added.

Training doesn’t stop once a dispatcher is hired. They are required to get 8 hours of training each year, and Ennis said there is still more training that goes on within the department. She said if somebody goes to a training and comes back with something really good that they have learned, that information will then be shared throughout all of the dispatchers.

“We’re trying to adjust with the times. The classes I took 15 years ago were a lot different than the training they’re doing now. And they’re trying to constantly keep up-to-date on the topics that are happening in the real world,” she said.

It’s not just regular job training used by dispatchers, but also cultural awareness training.

“We have a very huge hearing-impaired community here, so they have classes for that. We also talk about those with mental disabilities. That’s increasing every day, as well,” she said.

The 2010 Census showed that of its 28,500 residents, Boyle County has 4,500 who are deaf or hearing impaired. Ennis said almost every person who faces those challenges has video relay now, which allows the person in need to reach out to someone who can translate their needs from sign language, then call and report the emergency to local 911 dispatchers. She said there are grants and other resources available to make sure the citizens who need tools such as video relay are able to receive them.

Foreign languages are another area where communication through 911 is important, and the local dispatch center utilizes a “language line” which will allow the dispatcher to have the caller’s voice translated and then read back to them in English so they can get help as quickly as possible.

Ennis said she wants to start an outreach program with Kentucky School for the Deaf to help the school understand what dispatchers need to help provide services.

“We would go to them to learn sign language, and we would also like to teach them our side of things. When you call 911, this is what we need from you,” she explained.

Dispatchers often receive feedback, and Ennis said that is greatly appreciated.

“We appreciate the ‘atta girls.’ When you’ve dealt with a hard call, and that person calls you back and says, ‘Thank you. I don’t think I could have gotten through this without you,’ that means the world to us.”

In addition to citizens, Ennis said the city commission has been very good about showing its appreciation for the work done by local dispatchers. She said the feedback is so important because many times they take a call but never know what happens on the other end.

“We don’t know how it ended. We don’t get that closure; it’s almost like you’re left waiting, wondering what else happened, what else could we have done. So it’s always good to get little bits of appreciation for what you’ve done,” she said.

These are some of the things that can make being a dispatcher a difficult and stressful career, and Ennis said there are resources to help with that stress. She said Kentucky Post-Critical Incident Seminar, known as KYPCIS, is one support system available to help with the stressful nature of the work.

“They are now showing the effects of the traumas we deal with every day, the stress that builds up every day, and they’re helping us deal with it. Every one of our dispatchers is in the process of going through that. It’s a three-day course. They give you therapists to talk to, they tell you ways to handle the stress and they let you know you are not alone in this process,” Ennis said. “We don’t see the scenes, so we don’t have that form of trauma. But a good dispatcher pictures the scene. Every word they take, every question they ask, they’re building that picture in their head. The more information we have, the better the information the officer is going to have.”

She said the KYPCIS program has been in place for about two years, and although all local dispatchers have not gone through it, that is the plan. Once all have completed the program, she said they will do so again after two years.

Being a dispatcher is not something everyone can do, and Ennis said there is a special type of person needed to answer the phones during a critical time.

“We look for somebody who is very empathetic, who wants to make a difference,” she said. “We don’t do this for the pay, we do this because this is what we feel we were meant to do. I’ve heard a lot of people say I don’t dispatch, I am a dispatcher. It’s who they are.”

Equipping officers

The body camera worn by officers is approximately 3 inches tall and weighs just a few ounces. The camera automatically comes on when an officer gets out of the vehicle for incidents such as traffic stops. (Jeff Moreland photo)

Officer Adam Wilson demonstrated much of the equipment used by Danville Police officers, and most of it is kept on their belts. When combined with their bullet-proof vest, he said an officer can carry approximately 25 pounds of equipment that could be used while on duty.

Police Chief Tony Gray said equipping an officer costs approximately $12,000 each.

“They don’t get paid very much, so I feel like they shouldn’t have to pay for any of their equipment. The city does a very good job of making sure we have some of the best equipment. What you see here is some of the best equipment money can buy,” Gray said. He added that it costs about $8,000 for the equipment Wilson demonstrated, and that doesn’t include the cost of uniforms, which approaches $3,500.

The vest worn by all officers weighs around 6 or 7 pounds, Wilson said, and officers always wear this vest on duty. Gray added that when he started, the vests weighed about 15 pounds.

“Technology has come a long way,” Gray said.

Wilson said the vest will stop rounds from most handguns, but may not stop rounds from larger caliber weapons or rifles.

Assistant Chief Glenn Doan said vests have an expiration date, and five years is the life of a vest. He said a vest can not be used by another officer if someone leaves the department because they have to be custom fit to the officer.

All Danville Police officers use the same gun, and Wilson said that is a .40 caliber Glock. The same gun is used by each officer to ensure that everyone is trained with the same gun and could use another officer’s gun if needed. Wilson said officers also carry extra magazines and with each officer using the same gun, magazines could be shared between officers if necessary during a situation.

Doan said there was a time when officers were allowed to use a weapon of their choice, but the department has since gone to a standard issue across the department. He said the decision is based on research, including information from agencies such as the FBI.

An officer’s baton is another important piece of equipment on the belt, and Wilson said he has used it to break out windows in situations where a child was locked inside a vehicle.

Officers also carry a tourniquet to help stop bleeding if necessary. Wilson said an officer could come upon a person who has been shot or injured in another manner that is in need of pressure to stop bleeding, and the officer’s tourniquet can be applied before EMS arrives on a scene. He said it can be applied with one hand if necessary, for example if the officer is wounded and needs to apply the device to his own body. Wilson said the officers’ tourniquet has a place for them to write the time it was applied to help medical personnel know how long it has been in place when they treat the victim.

Body cameras are a very important part of the officer’s equipment, and Doan said each officer wears one at all times on duty. He explained that when an officer gets out of a vehicle for an incident such as a traffic stop, the camera automatically activates. The same thing happens if an officer removes the rifle mounted inside a police cruiser.

Once an officer returns to the department at the end of a shift, Doan said the video from the camera is automatically extracted when the officer pulls into the parking lot. Cameras are docked and charged after the shift, and the video from the shift is stored for future use.

The body cameras cost approximately $800 each, and the department has a service agreement with the manufacturer that ensures good equipment is kept in place. Doan said the department pays fees throughout the year to the company, and if something goes wrong with a camera, the company will replace it. He said something such as a focusing issue will normally happen before the camera is actually broken in the line of duty.

Using the Taser

Jason Weathers, a member of the 2020 Danville Police Citizens Academy, gets instructions on using a Taser from Officer Ben Ray during Tuesday night’s class. (Jeff Moreland photo)

Some officers carry pepper spray, but it is not required. One tool all officers do carry is a Taser. The Taser allows officers to subdue a subject with an electrical shock without having to result to using a gun, providing a non-lethal option to the officers.

Doan said every officer uses a Taser, and each officer is “tased” in training. He said the device can be used to gain compliance from a subject while using the least amount of force possible while doing the least amount of damage to a subject while getting them under control.

Gray said when the department first started using Tasers, the injury rate to officers and citizens immediately went down.

Officer Ben Ray and Sgt. Chase Broach are Taser instructors for the Danville Police Department, and they demonstrated the device to the class. They told the members about the uses and functions of the Taser, and Broach donned a protective suit that allows a person to have the device applied without harm.

Using training cartridges, members of the class were given the opportunity to fire a Taser at a “suspect” in a simulated situation.

Although a Taser deploys an electric-type current to subdue a subject, the two contact points also feature a metal probe with sharp ends. Officers can choose to use the laser sight on the Taser to help make sure they hit the subject in the most effective area. Broach said the laser itself is also a great tool.

The probe of a Taser provides an electronic sensation that brings about a condition known as neuromuscular incapacitation, which was described by officers to be much like a “Charlie horse” in a person’s muscles. (Jeff Moreland photo)

“When you see that laser, you realize they’ve got a Taser and there’s a psychological effect to seeing it. That red dot is going to tell you where that top probe is going to go. So already, it works as a de-escalation technique just to point it at someone, because they can see where it is and what’s going to happen to them.”

Ray added that the Taser can possibly be more effective than a gun because an officer is not likely to shoot them for not complying, but the subject knows the officer can and will use the Taser.

The electronic sensation from a Taser is known as neuromuscular incapacitation. Broach described it as a giant “Charlie horse” to the muscles in the area between the two probes.

Although the Taser is not intended to be a deadly weapon, Ray said the manufacturer does suggest using it in areas such as the back if possible because there are less vital areas to possibly be damaged, and to try to avoid areas like the heart. He said officers are trained to aim off center of the body while “splitting the hemisphere,” which means to aim for an area that will hit part of the subject’s upper and lower body.

Ray said the range of a Taser probe is approximately 25 feet, and getting the probes to strike approximately 12 inches apart is the ideal range. Broach explained that avoiding the chest is also recommended because the area doesn’t typically have as much flesh, and it is possible for the probes to bounce off that area. Still, he said the Taser is the best tool in his opinion.

“The car and the radio are tied for second, but I would say the greatest law enforcement tool is the Taser. It is a psychological advantage,” Broach said.

Next up: Week 3 of the 2020 Danville Police Citizens Academy is scheduled to include information about arrest procedures, including when can officers arrest and for what things can they arrest. Detectives will also be in attendance and demonstrate fingerprinting.