‘Here all along’: Art Center of the Bluegrass hosts traveling Native American art exhibit

Published 5:43 pm Friday, November 6, 2020

- Fred Nez-Keam draws inspiration from Navajo culture in the design of his flutes. - Photo submitted

The Art Center of the Bluegrass has been chosen to host the Kentucky Arts Council’s traveling exhibit called “Native Reflections: Visual Art by American Indians of Kentucky,” according to a press release. The exhibit will run Nov. 5 to Dec. 19. Visitors are required to wear masks and follow social distancing protocols at the Art Center, and gallery hours are 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays and 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturdays.

The exhibit consists of 23 works of art created by 12 Kentuckians who identify as American Indians of enrolled tribal membership or who are not enrolled but are Native-inspired. The work submitted was reviewed by a panel of American Indian artists and members of the Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission for inclusion in the exhibit, according to the release.

Mark Brown, folk and traditional arts director for the Kentucky Arts Council, said the exhibit is a partnership between the Kentucky Arts Council, the Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission and the Kentucky Heritage Council.

“One main goal that the arts council and heritage council agreed on for this exhibit was to challenge a popular misconception that Native Americans or American Indians are no longer living in Kentucky,” he said in an email. “An art exhibit can be a powerful way to counter that misunderstanding, by showcasing American Indians’ artwork and demonstrating that they are indeed living here, and have been here all along, actively contributing to today’s cultural landscape.”

Brown said the exhibit consists of different art styles and individual and cultural expressions and is by people descended from several different tribes.

Also, on Nov. 19, the Norton Center for the Arts at Centre College will host a virtual program called Culture + Giving Thanks, which will look at Thanksgiving traditions from perspectives of Indigenous people from Kentucky, according to the release. This will feature two artists from the exhibit, Brigit Truex and Fred Nez-Keams, as well as Martha Redbone, an American blues and soul singer of part Native and African American descent, and chair of the Kentucky Native American Heritage Commission, Helen Danser.

Two artists whose work is featured in the exhibit are Nez-Keams and Jannette Parent, who shared information with the Advocate-Messenger about their backgrounds and featured artwork.

Fred Nez-Keams

Nez-Keams is an enrolled member of Navajo Nation and grew up in Navajo, New Mexico. He has lived in Kentucky in Anderson County for the past 15 years. He makes Native American flutes, infusing his Navajo culture into the design. He said he incorporates turquoise into them because the Navajos are jewelry makers. They are also pottery and rug makers, he said, so he reflects that as well. His pieces included in the exhibit are titled “Yellowknife Navajo Flute 1 & 2.” He carves his flutes from Kentucky wood, specifically red cedar wood.

When Nez-Keams was about 20, he said he fell into a depression after his mother died, and he left his reservation and moved to Flagstaff, Arizona. One day he was sitting on the porch and suddenly heard a beautiful sound. He looked up and saw one of his family members was playing the flute. After that, the memory and meaningfulness he associates with the Native American flute has stayed with him. Before that, when he was a little boy, a friend of his had a flute and gave him one of his own.

“It was always in my heart ever since I was a little boy,” he said.

When he was on the reservation, he said he couldn’t find anyone who could make the flutes. He found someone who could make them in Kentucky and has been making them for about 15 years now. When he started, he discovered Native American flutes are expensive, so he decided to set one price for his flutes so people could more easily afford and play a flute, he said. He has learned a lot about the flute and how much it has touched people, he said. The flutes used to only be made with five holes, he said, and now they can be made with six and used to play with other instruments and many styles of music.

“It’s just been amazing just to see how much it has progressed,” he said.

Now, Nez-Keams writes his own music and is part of a band. He started performing at Native American pow-wows, then bookstores and libraries, and now his band performs at festivals and other events. He doesn’t read music notes, but he can tune a flute and loves to play with any instrument.

He said he never knew he would be a performer or speak about his culture. Now, he introduces himself in Navajo when he starts a presentation and tells stories about his flutes and his culture, and he also tells of his time in government boarding school as a child. He wasn’t necessarily required to go, but he said his family was poor, and there was no food, so in some ways boarding school was a place to stay safe. However, the boarding school did not allow the Native Americans to speak their native languages and had them cut their hair. They also brought Christian churches to the boarding school. Nez-Keams said now, he is Christian, but he grew up in Native American church, so he holds onto his Navajo traditions “on the side.” He understands the Navajo language but is only half fluent in his speaking, he said.

He said his family was very traditional growing up. He grew up on horses every day, which he rode bare-back. He remembers traditional Native ceremonies and celebrations. His mother weaved rugs, and his uncle and grandfather were medicine men. At the boarding school, one of his dorm advisers was Apache and taught him and other “little Navajos” how to dance the Apache Crown Dance, he said. He said he wants to share his culture when he gives presentations and makes his flutes, and show the everyday life he remembers — waking up, saying prayers, taking care of livestock and caring for grandparents at the reservation where he grew up.

Jannette Parent

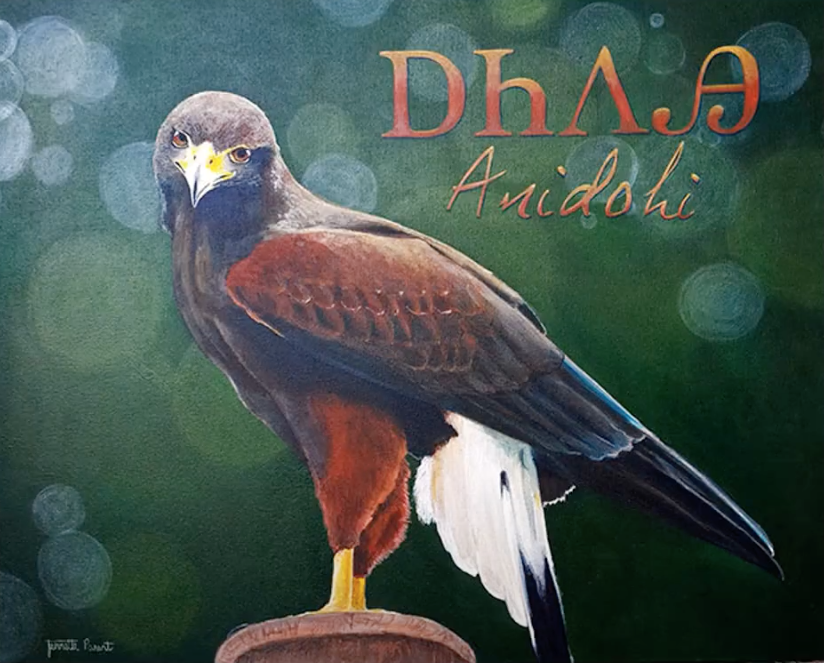

- Janette Parent’s acrylic painting Anidohi (The Messenger) features a hawk and Cherokee language. – Photo submitted

- Janette Parent’s acrylic painting Utsonati (It Rattles) features a rattlesnake and the Cherokee language. – Photo submitted

Parent’s pieces, Utsonati (It Rattles), which features a rattlesnake, and Anidohi (The Messenger), which features a hawk, each came to her in her dreams, she said. Both are acrylic paintings.

She said she grew up respecting and admiring snakes.

“Here in Kentucky, most people hate them and kill them for no reason,” she said in an email. “The Cherokee feeling toward snakes is one of mingled fear and reverence, and every precaution is taken to avoid killing or offending one, especially the rattlesnake.”

As for the painting of the hawk, she said she lives “out in the country and sees them daily” and loves them.

“In Native American culture, the hawk is associated with the power of vision,” she said. “It is also considered a messenger who brings communications from the spirit world and the unseen. Whenever I see a hawk flying overhead, I pause and listen for any messages it may be bringing.”

Parent was born in California, raised in Oregon and currently lives in Caldwell County in Kentucky. She is not an enrolled member of Cherokee Nation but has several Cherokee ancestors on her maternal side. Her artwork is Cherokee-inspired and features Cherokee language, along with its pronunciation and meaning.

As she learned the Cherokee language, she had difficulty memorizing new words and the unique syllabary alphabet, she said. She found using the title of her paintings to describe the subject helped her remember the words.

“Now, whenever possible, I tell a story with the painting and pass on the Cherokee stories, myths and history that I have learned,” she said in an email. “At last count, I had completed over 85 paintings in this series.”

Another piece of why she features language in her work is because she said language is an important in preserving culture.

“Many words that are descriptive of cultural mannerisms, feelings, events and ceremonies are only identifiable in the native tongue,” she said. “There’s no comparable word in the English language.”

When she moved to Kentucky in 2004, she learned about a Cherokee language class and fell in love with the language. She is not fluent, but she said she loves it and will keep practicing it.

She said she thinks people will be surprised by the diversity of the art exhibit in media and subject matter.

“There’s something for everyone in this exhibit,” she said in an email. “As for my art, I hope that it inspires anyone with Native American ancestry to learn more about their tribe, the people, and where they come from, before it’s too late. People often tell me they have Native ancestry, but know nothing about the language, mythology, or the culture. Or they only know false stereotypes. That is disheartening.”

More details and registration for the Nov. 19 Culture + Giving Thanks event can be found by visiting nortoncenter.com/events/giving-thanks/