KSD remembers faithful employee William Tompkins

Published 4:43 pm Monday, February 15, 2021

- Photo of the Danville Colored Fair held in August 1905. Used with the permission of the Boyle County African American Historical Society.

BY JOANN HAMM

KSD, Jacobs Hall Museum

William Tompkins, employed as a servant by the Kentucky School for the Deaf for 55 years, served more than two and a half generations of staff and students before he died. Everyone knew him as “Uncle William” or “Uncle Bill” Tompkins.

He was on hand at the 1917 KSD reunion, dressed in his Sunday best, to meet “his white folks,” and received a warm greeting.

Tompkins was born in the 1830s as a slave, and was owned by the Tompkins family. He did not know the year he was born, but his son, William Tompkins, estimated his father’s age when he died as 86 years old. The large Tompkins estate lay south of the deaf school down Second Street and extended along Hustonville Road. In 1866 the newly emancipated William Tompkins was first employed by the deaf school.

Most of what we know about William Tompkins comes from a few official records and anecdotes published in the Kentucky Deaf-Mute, later renamed The Kentucky Standard. The school did not have many employees, and since the staff was on call 24/7 for 10 months each year, everybody was expected to do a wide variety of jobs.

William was referred to as a “servant” and his tasks ranged from building repairs, yard work, painting, farm work, gardening, and taking care of the vast school lawns.

An institution report for 1882 noted that when the pupils had a picnic in the woods in early May there was an unexpected incident:

“As the servants were setting up the refreshments a serious accident befell William Tompkins. He was hauling supplies to the grounds when the horse became unruly. In endeavoring to control him, Tompkins was thrown violently against a fence, straining his knee, and bruising him severely. He was at once conveyed to his home. Fortunately, no bones were broken and his injuries, though painful, are not as serious as they first appeared to be. After the accident many of the younger boys visited him daily while he recuperated.”

“Over the years, student reporters wrote about “Uncle William.” For example, in 1886 the writer observed: “WM. TOMPKINS trimmed the hedges last week. They are now pretty,” and in 1887, “The outside of our carpenter’s shop was whitewashed by William Tompkins, our colored man.”

A reporter from the Colored School wrote: “‘Uncle Billy’ Tompkins helped the boys to make the flower beds in our yard. The boys like him very much because he is kind to them.”

“Uncle Bill” Tompkins requested time off from work far in advance in the late 1890s and 1900s to help organize the annual Colored Fair. For years he served on the board of the Colored Fair Association in Boyle County.

The week-long fair brought visitors from Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana to Danville. The Cincinnati-based Queen City Railroad offered excursion packages with special fares for fair-goers.

In 1899, a Kentucky Standard reporter noted: “The Colored Fair Association of Danville, about the best in the state, has decided to hold its annual fair as usual the coming summer. Our ‘Uncle’ William Tompkins was re-elected vice president, a position he has held for many years past. It is alone worth the price of admission to see ‘Uncle Will’ and his badge in the judges’ stand, bossing the 4:40 ‘hoss race.’”

When the school broke ground for the foundations of two new residences for the younger students in 1903, “the honor of lifting the first shovelful was given to Uncle Billy Tompkins, our faithful old colored servant who has been connected with the school for thirty-seven years,” a Kentucky Standard writer reported.

Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins were favorites of both the boys and the girls. In 1907 a reporter for the girls wrote: “Last Sunday Miss Laura Adams took Mary Scott, Celia Smith, and Maggie Miles out to visit Mrs. Tompkins, the wife of Uncle William Tompkins, and returned home reporting an enjoyable time.”

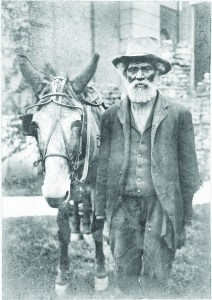

“Uncle Will” Tompkins and his mule, Jack. (Jacobs Hall Museum archives)

By then the Tompkins lived at 133 East Walnut Street. According to the 1910 U.S. census, Tompkins’ birthdate was estimated to be 1838, making him about 72 years old in 1910. William Tompkins owned his own home, could read and write and was employed by Kentucky School for the Deaf as a “flower gardener.” He had been married to Pauline Williams Tompkins for 29 years. She was 52 years old in 1910.

An article in the March 17, 1910 Kentucky Standard noted the passing of “Uncle Will” Tompkins’s faithful companion “Jack,” a mule purchased years earlier that Tompkins used to mow the school lawns.

Jack “was remarkably strong, but that which separated him from others of his class was his great intelligence. “Uncle Will” never tires of talking on this subject, and all of us have had ‘proof’ of it in the sight of Jack steering the lawnmower around trees, flowerbeds, and obstructions while his aged driver dozed peacefully on the seat, with drooping reins. For the last year or two Jack had been growing feeble and he was relieved of all work except light jobs now and then. His remains were interred in a corner of the pasture he loved so well.”

In 1916, Tompkins was about 78 years old and was slowing down. From the Kentucky Standard: The lawn mower has been placed in commission again, but “Uncle Will” who from time immemorial has performed that office no longer drives it, being succeeded by his son “Bob” Tompkins. “Uncle Will” still reports daily for duty and performs light work around the kitchen. He is as great a favorite with the children as ever.”

By 1920 Tompkins was confined to home, unable to work at all. After Christmas in 1920 and again in 1921, the boys of the YMCA held benefit shows with the proceeds going to the Tompkins family.

In the March 17, 1921 issue of The Kentucky Standard, editor George McClure published William Tompkins’ obituary entitled “A Faithful Servant Passes.”

“‘Uncle Will’ Tompkins for fifty-three years a faithful servant of this school, passed away Sunday morning at his home on Walnut Street. He did not know his exact age, but he was over eighty. Death was due to pneumonia. He was a slave of the Tompkins family in his youth and was first employed by the school the first year after the Civil War closed. In his prime he was a splendid specimen of physical manhood, tall, well proportioned, and with great strength.

He was loyal to his ‘white folks’ which in this case meant the school and the deaf, faithful in his work, and cheerful in its performance. The last few years of his life, his tasks had been very light — helping around the kitchen, or driving his dumb friend, Jack, who grew old along with him, on the lawn mower. He had been unable to walk for a couple of years past, but was kindly cared for by his wife, and his white friends did not forget him. The funeral was held Tuesday afternoon at two o’clock in the Colored Methodist Church on Walnut Street of which he had been a lifelong member. He was a humble and sincere Christian, and death had no terrors for him. The church was packed, for Uncle Will was respected and many friends turned out to do honor to his memory. The officers and pupils of this school sent a beautiful wreath. The interment was in the Colored Cemetery on Duncan’s Hill.”