Campaign signs are a blight – take them down

Published 8:30 am Friday, November 11, 2022

JOHN REITMAN

john.reitman@bluegrassnewsmedia.com

I don’t know much about John Quincy Adams’ political views, but he wouldn’t get my vote if he were running for office today.

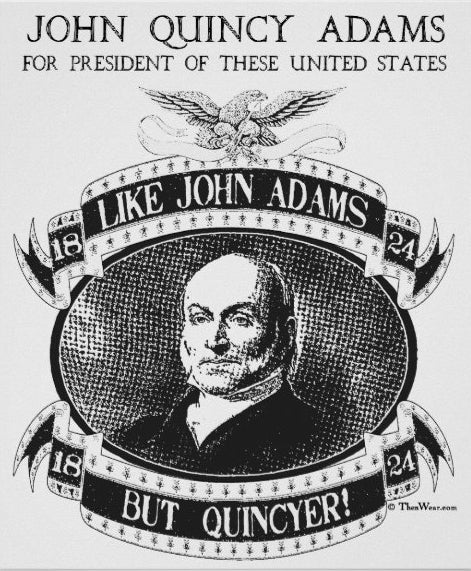

The sixth president of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829, Adams, according to lore, is credited for coming up with the idea of campaign yard signs in 1824 in his race for the White House against the likes of Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay. Now that we know what a cancer that idea has blossomed into, I would find it difficult to support Adams today, even if he held the keys to fixing current problems like soaring inflation, high fuel prices and an effective border policy. In fact, now that Election Day has passed, I’d have one message for Adams: “It’s over. Take down your signs.”

With the coming of every election cycle, yard signs sprout like weeds and are equally noxious in their appearance. They litter neighborhoods and highly trafficked roadways like dandelions. And like weeds, campaign signs serve no apparent purpose other than to grab the attention of the politically disengaged, unmotivated and easily coerced passerby.

As much of a turnoff as campaign yard signs are, the concept is as intriguing as the signs themselves are distasteful. The courts have determined that yard signs are a form of protected speech. But why, in a secret ballot system, do people feel the need to broadcast their political beliefs through yard signs? This might come as a shock to John Quincy Adams as well as my neighbor down the street, but no one cares what someone else thinks about one candidate over another, or if they belief in “yes” on this, or “no” on that.

As I drive though my neighborhood, I cannot help but wonder in today’s polarized political climate if the need to voice an opinion on hot button issues such as Amendment 2 is worth causing a rift with a next door neighbor who proudly broadcasts an opposing view. Neither side will convince the other to change their mind, so I fail to realize the sense in trying to influence those you don’t know who are driving past both and saying to themselves with an air of common sense “that must be awkward.”

Are the political leanings of others so easily swayed that a plastic placard can make them cast aside everything they believe when they cast a ballot? If that’s the case, these people probably never had any real opinions anyway. And that is a problem, especially in Kentucky where a recent study showed that only 17 other states have a more disengaged voting public.

Studies also show that yard signs in fact have little outcome on elections. Political scientists who have studied the effectiveness of yard signs agree that, at best, name recognition generated by yards signs is worth a point or two, but mostly in hotly contested local elections. To prove that point, researchers at Vanderbilt University concocted a fictitious city council candidate by the name of Ben Griffin and flooded a well-traveled road with his campaign signs. A subsequent survey asked local voters to list their top five choices for council, and the fictitious Ben Griffin was named in the top three of most responses.

Early campaign signs might have worked for Adams. In 1824, he emerged from a four-person race that ultimately was decided in the U.S. House, making him the only president to win an election without a plurality of electoral votes.

What is worse than political campaign signs in the days and weeks leading up to an election – either today or in 1824 – are signs that linger days and weeks after an election. Signs that support losing candidates and causes make the homeowner look like they’re not paying attention, or they’re on vacation. Those who leave signs up for a victorious candidate or cause come off as gloating, and no one likes a sore winner.

It’s over. Take down your signs.