Lessons learned: Boyle inmates find chance to beat addiction with in-jail drug rehabilitation program

Published 6:00 am Saturday, January 21, 2017

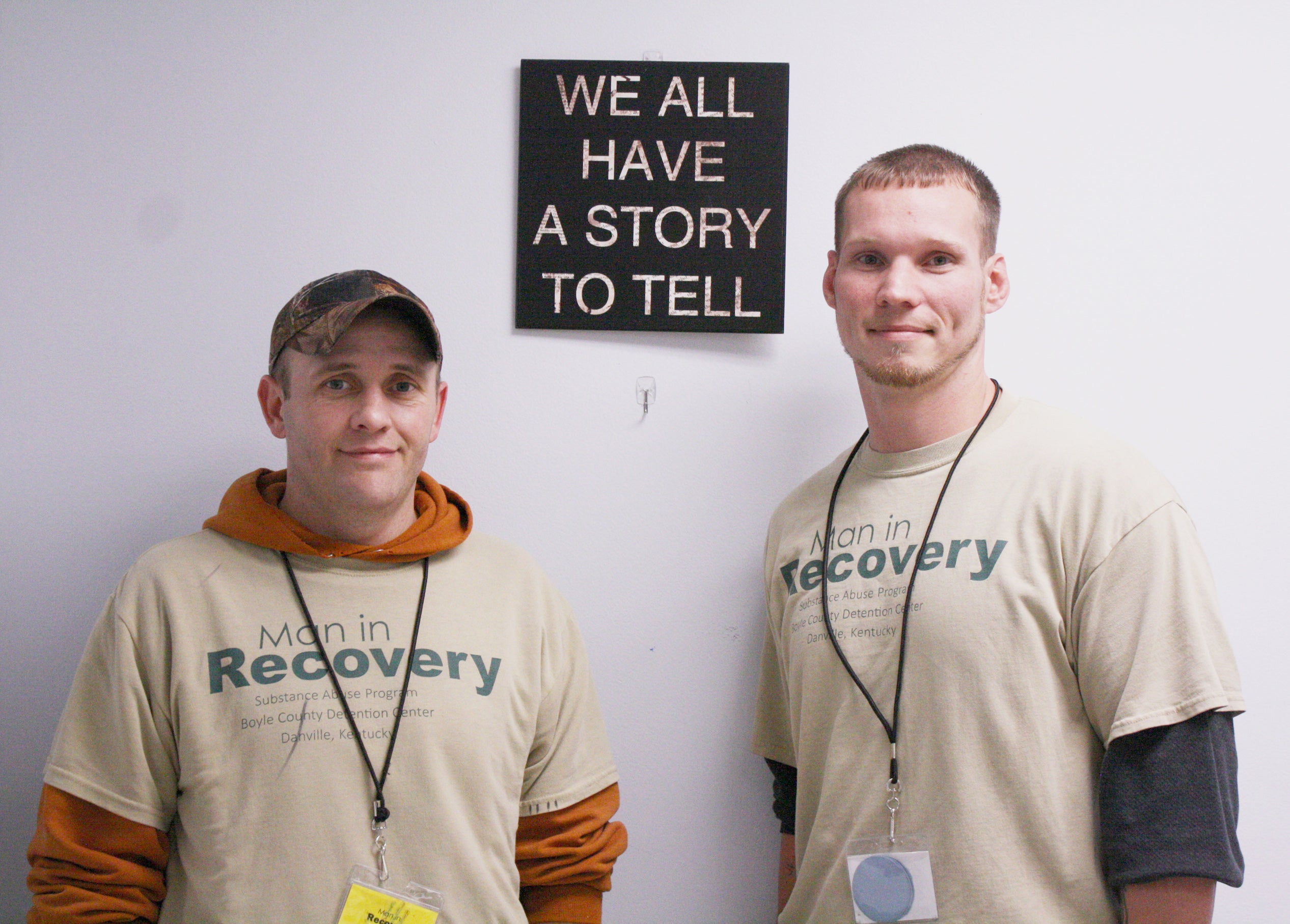

- Former inmate Edward Hamilton stands with William Newman inside the treatment unit at the Boyle County Detenction Center. Both struggled with opioid addictions beofre entering the treament program.

For Boyle County Detention Center inmate William Newman, an addiction to opioids started with being prescribed Tylenol-Codeine when he had a broken leg at the age of 13.

While on the prescription, he began misusing the pills. After he finished the prescription, he said he found other means of obtaining the pills and eventually started using OxyContin and heroin.

Edward Hamilton, a recently released inmate, was also prescribed opioids which led to addiction. In his 20s, he started using OxyContin. While on a prescription, he began abusing the medicine and returned to the doctor several times to try to obtain more pills.

Hamilton said he returned to the doctor after a couple of weeks of being on the prescription and complained about back pain from construction work. The doctor gave him another prescription.

After only one week, he returned to the doctor and was given more pills — but he was told to not come back. Hamilton said he found other means of getting the pills after that.

Newman and Hamilton said obtaining more pills was easy to do outside of doctors’ offices.

Newman said he could get some pills from other students at school who had parents on the medications.

“It was easy for me,” he said.

Hamilton said when he was growing up in southern Kentucky, “I say in seven out of 10 houses … somebody in that house is taking medicine, getting medicine from a doctor.”

“The pills, it felt like they just helped me. It made the days better — it made life better,” he said. “I lived for the pill. I devoted my whole life to drugs, pills.”

Hamilton completed a substance abuse program (SAP) at the Boyle County Detention Center Jan. 12, and Newman will complete the program Feb. 2.

Program has helped hundreds

About eight years ago, Boyle County Jailer Barry Harmon told the Department of Corrections that he wanted to provide a treatment program for inmates in the Boyle County Detention Center, SAP Director Liz Cook said.

The detention center was then chosen to hold a substance abuse program (SAP) in the jail for male inmates and hired the rehabilitation organization Shepherd’s House to run the program.

SAP is a six-month drug and alcohol program that provides treatment to 40 male inmates at a time, Cook said.

The men in the program are assigned to SAP through the Department of Corrections, she said.

Since the program started, she said they have helped about 640 male inmates.

“A lot of guys come from environments that were filled with drugs and alcohol growing up … or they experienced some childhood trauma,” she said. “They come to addiction through a lot of different routes.”

“A lot of people are driven by fear and materialism and their life is based on that,” said Newman, the inmate preparing to graduate. “Our life was driven on that high.”

“You know, we mean well and we’ve got the heart of gold and we wanna do the right thing, and we’ve got full intentions on doing the right thing,” said the recently graduated Hamilton. “It’s just instead of going right, we go left. We have good intentions, we just aren’t able to do them. Just because we messed up and done bad doesn’t mean we’re bad people — we’ve just got a problem.”

“These guys are just like anyone you would meet at your family’s holiday celebration or at church or at the work place,” Cook said.

Hitting rock bottom

When Newman started using pills, he realized that they made him a different person.

“I’m a nervous person. I’m not real comfortable around people — it made me comfortable around people.”

The pills began to numb him emotionally, he said.

“It made me mask who I was, but made me be more open towards other people, Newman said. “I felt like I had a better relationship with people. I liked the way it made me feel.”

After serving a five-year sentence for receiving stolen firearms, he said he wasn’t ready to change.

“I feel like if you use opiates and you’ve not hit your very rock bottom, and you’re not willing to change everything — absolutely everything — then you’re not going to accomplish anything,” Newman said. “At that point in my life, that’s where I was.”

“When anyone is in an addiction, it’s like a love-hate relationship,” Hamilton said. “You know all the bad it’s going to cause, but you still love it so much.”

“You may choose to start using, but eventually when you move from using to abusing long enough, you become dependent,” Cook said.

The definition of addiction, according to Cook, is “you can’t stop the behavior, even though it’s harmful for you.”

For Hamilton, he moved on to heroin when OxyContin wouldn’t give him the high he wanted anymore. While on heroin, “I’ve overdosed a total of 14 times,” he said.

“I can look back now and see that I’m not that person, but it made me something to where I didn’t care who was around me, who it destroyed, whose lives it destroyed,” he said.

Before Newman realized he wanted to change the way he was living, there was an incident where he took a shot of heroin and then went driving. He ended up passing out at the wheel and nearly driving his vehicle through a house.

“And it wasn’t until that day that I was ready to do something different,” he said. “I didn’t want to live that life anymore. I let something that seemed so small to other people ruin the best of me. I threw so much away.”

Newman said that nobody really understands what they are doing to themselves or to others until they’ve hit rock bottom.

“They have to have an eye opener — something that really clicks for them to wake up and realize, ‘this is where I’m going in life,’” he said. “You’re your worst enemy at that point. You’re the only person dragging you down.”

A new life

Newman said being a part of the drug treatment program at the Boyle County Detention Center has made him realize that he doesn’t have to live the way he used to anymore.

“It’s taken this program — this program right here, it made me realize what I wanted and where I wanted to be and the choices I had to make and the sacrifices I had to go through,” he said. “It’s been a blessing all in itself to even have a chance to have a second chance.”

“They deserve every chance that they can to be successful,” Cook said.

After serving a 23-month sentence, Hamilton was released on Jan. 12 and graduated from the in-jail drug program.

“I would just like to give this place a hand,” Hamilton said. “They are really here to help us. They care about us, it’s not just a job for them. Support like that — that’s what helps us.”

“It’s driven by them, for them, with our guidance and correction and that’s what makes it work,” Cook said.

Hamilton returned to a job he’s had for 13 years, and has a new apartment in a different neighborhood. It’s helpful to get him out of his old environment, he said.

Hamilton has learned several tools and skills from the program and is ready for a fresh start.

“I know everything I need to know, I’ve just to put it all together now and make it work,” he said. “Just staying positive and being around positive people and keeping a positive and active spirit.”

“We always tell them that it’s not necessarily about becoming somebody new, it’s about becoming who you were meant to be or who you already were,” Cook said. “In a way, it’s unlearning a bunch of stuff and really just becoming who you were meant to be.”