Bate Middle officially renamed John W. Bate Middle School

Published 9:11 am Monday, August 14, 2017

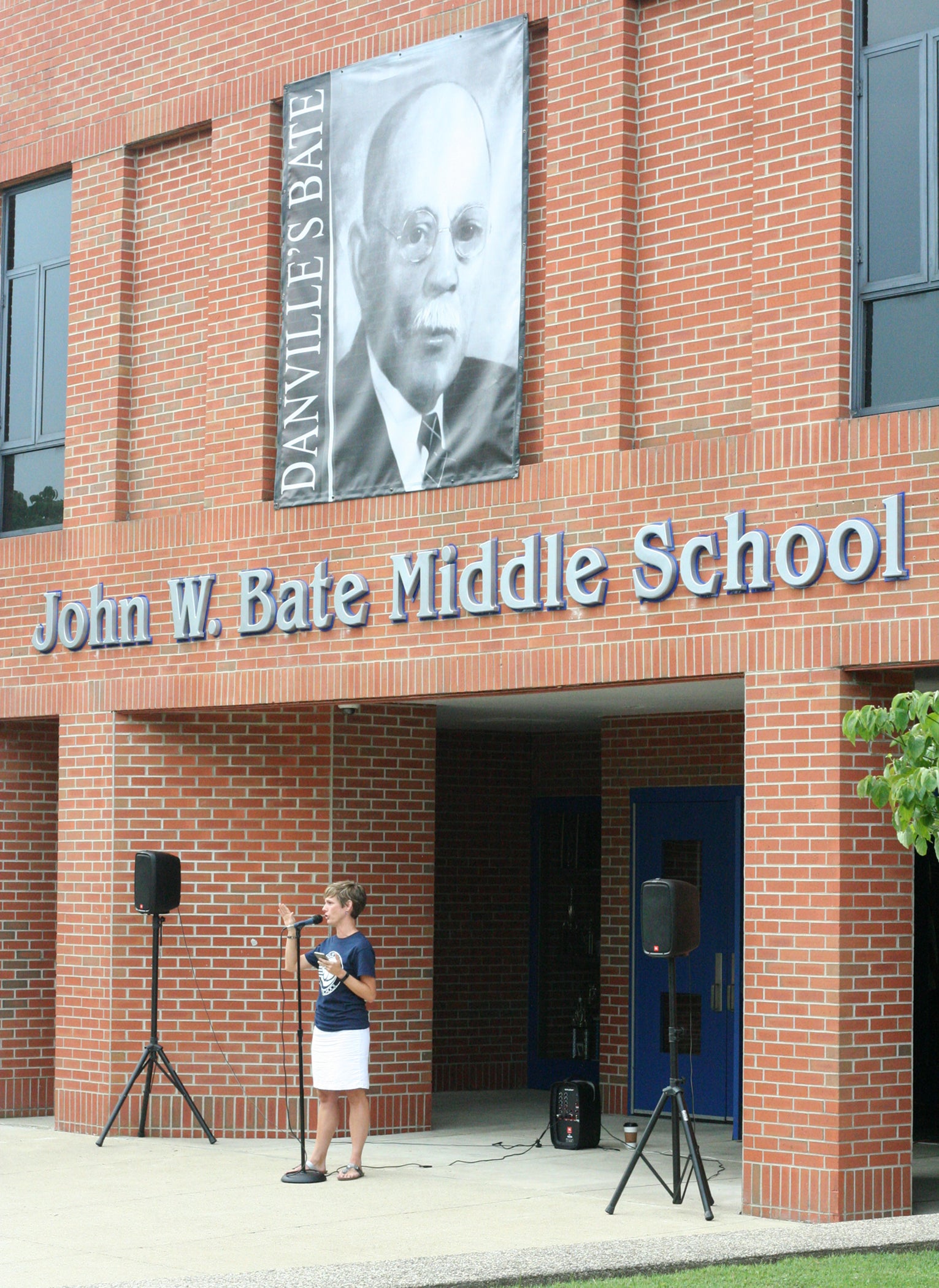

- Kendra Peek/kendra.peek@amnews Sheri Satterly, the principal of the newly renamed John W. Bate Middle School, addressed the crowd on Saturday.

Kendra Peek/kendra.peek@amnews

James “Jackie” Lewis, a 1960 graduate, loaned his letter jacket to Glenn Ball with the Bate School Alumni Association to show during the rededication of the John W. Bate Middle School. The jacket will be showcased at the Boyle County Public Library beginning Monday.

More than 100 people gathered Saturday for the dedication of the John W. Bate Middle School, a change in name giving full credit to the man the school was named after.

“History makes harsh demands of us all,” Superintendent Keith Look said, quoting “Invisible Man,” written by Ralph Ellison.

“In those hard demands come opportunity for us to resolve, to fix, to address, to come together and celebrate. That is what we’re doing here today with John W. Bate,” Look said. “It takes all of us to figure that out — alumni, community, school board, educators, parents and students.”

John W. Bate was a former slave who, after obtaining freedom with his family in 1862, attended Berea College in the late 1800s. He came to Danville to teach in a one-room school, named the Danville Colored School, spending 59 years in education in the city.

The school was named Bate High School in 1912.

When Bate retired in 1941, the school had expanded to be a 20-room school with 15 teachers and a two-thirds gymnasium. The school was an accredited high school and enrollment had increased from six to 600 students.

In 1964, the schools integrated, and the school became Bate Junior High. That building was torn down in 1978, after the current building was constructed. It was named the Danville Bate Middle School, with “Bate Middle School” written on the side until earlier this week.

Look commended the Bate High School Alumni Association on helping the board remember what the priorities of the district are. Look then introduced Principal Sheri Satterly, “the first principal of John W. Bate Middle School.”

Satterly, an alumna of the then-Bate Middle School and the Danville High School, became principal at Bate last year.

She recognized the past school administrators who were attending the event.

“I’m not sure I’m deserving to be part of such a wonderful group … But I sure am honored,” she said.

Kendra Peek/kendra.peek@amnews

J.H. Atkins speaks of John W. Bate, as Bate, addressing the group during Saturday’s rededication of the school.

Other speakers included Michael Hughes, president of the Boyle County African-American Historical Society; and Glenn Ball, a 1960 graduate of Bate High School and member of the Bate High School Alumni Association.

“I want to give it up for the Board of Education. You put respect in the name when you added ‘John W.’ You gave the man respect,” Hughes said. “… If someone walks through this door, the first thing they’re going to think, ‘Who was this man? What did this man do? Why is his name across this great big building?’ Then they’ll start to think. ‘He must have been somebody.’ John W. Bate was somebody.”

Ball shared how he asked three things of the board regarding the school: to maintain the bulldogs mascot; to change the name from Danville Bate Middle School to John W. Bate Middle School; and to return the school colors to purple and gold.

“I have to commend the alumni association. We approached this very diplomatically … We didn’t throw bricks through doors. It was a very honorable process and it worked,” he said. “I’m just a name and a face.”

Ball brought with him a letter sweater from 1956, belonging to John Davis; and a letterman jacket from 1960, belonging to James “Jackie” Lewis. The jacket will be placed at the Boyle County Public Library this week.

“The legacy of Bate High School lives on,” he said.

He also pointed out a few of the other alumni who had traveled to the event.

After the event, Ball said the day was “beautiful.”

“It was a labor of love. … And they listened,” he said.

Kendra Peek/kendra.peek@amnews

A large crowd gathered at Saturday’s dedication, many representing the purple and gold of the Bate Alumni Association, and the former Bate High School.

The end of the ceremony was opened up to anyone in the audience who wanted to speak. Former and current faculty members shared their love of the school, and local historian Charles Grey showed the group a diploma from the Danville Colored School, the predecessor to the Bate High School, which became Bate Junior after integration.

Doris Trumbo, who attended Bate school until integration in 1964, said she thought it was wonderful the name had officially been changed to recognize the man that made a difference in the lives of so many black people in Danville.

“I’m glad I was able to experience it,” she said.

Another student who experienced segregation and integration was Minnie Frye. She explained that Bate meant so much more to the black community than just a school. It was a part of the community at large.

“People in the community would come support things at the school, whether they had kids in school or not,” she said. “Bate meant something to the community in ways I did not realize until I left.”

It wasn’t until she started at Danville High School in grade 10 that Frye said she realized the impact Bate had on her and her black classmates. There were many students, particularly young black men, who dropped out when the schools integrated — men who would have likely received their diplomas had they stayed at Bate.

Kendra Peek/kendra.peek@amnews

Danville Independent Schools Board Member Troy McCowan at the John W. Bate dedication Saturday.

In other cases, there were black students passed over for leadership roles because those positions were selected by teachers or by the majority of the student body, and the black students were outnumbered. This kept those students from strengthening their leadership abilities like they might have at Bate. Over the years, Frye said, this changed — now, she pointed out, it’s nothing for black students to be class presidents or homecoming queen or king.

“Overall, I had a good experience at Danville High School. It took me leaving Bate to see how important Bate was to the students and the community,” she said. “I’m glad the school board saw the importance to the community. This shows the school board was united with the community in recognizing the importance of Professor Bate and Bate School to the community.”

To see photos of the rededication.