Are defendants in Boyle and Mercer counties kept locked up for being poor?

Published 6:47 am Saturday, June 23, 2018

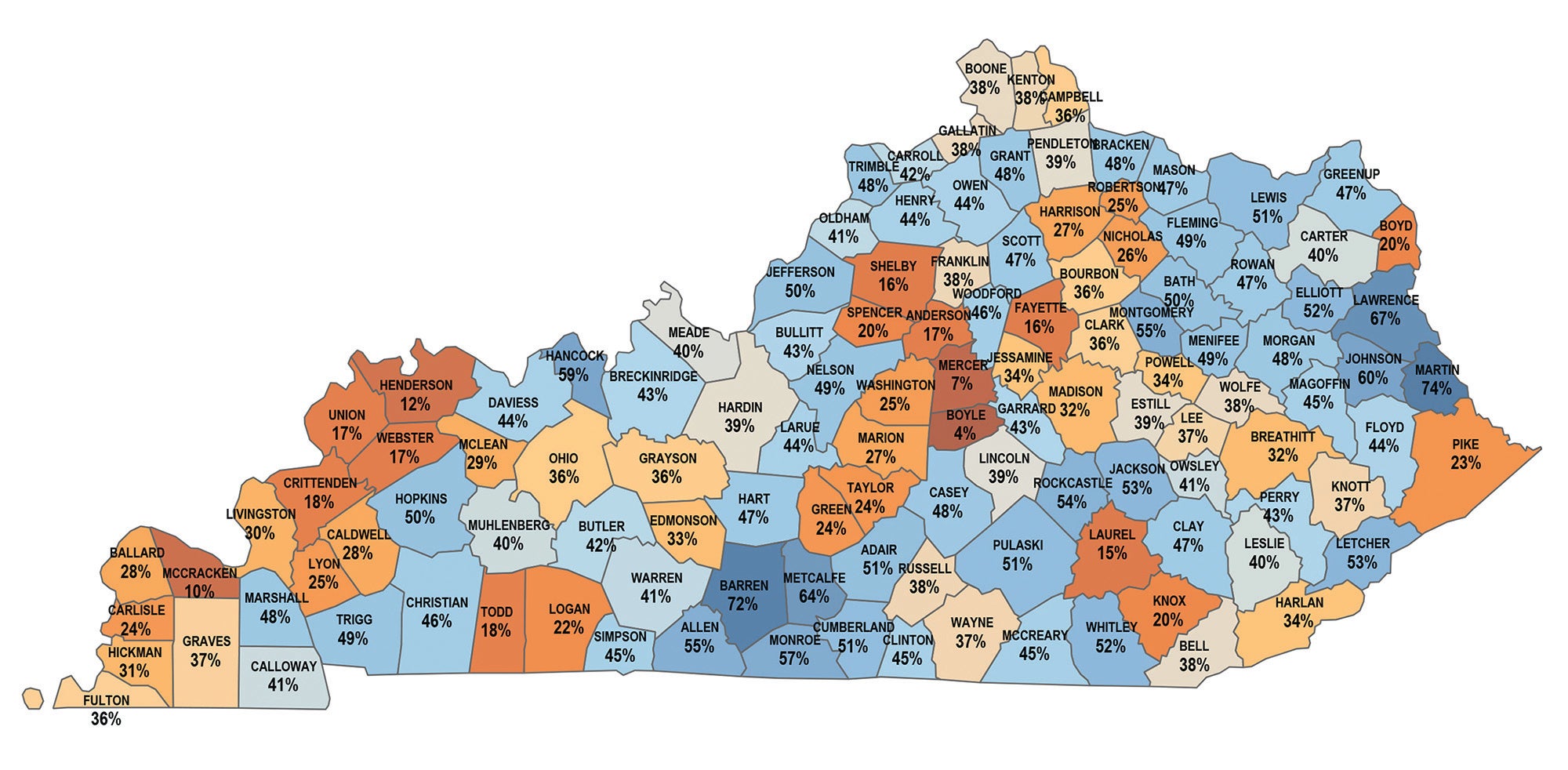

- Administrative Office of the Courts/Department of Shared Services Defendants in Boyle and Mercer counties had the lowest chances to get out of jail without paying money in 2017, according to Pretrial Services data.

Data shows local judges require financial bonds most often in Ky.

When Tonia Stinnett was charged with a felony, she went to jail. That much isn’t surprising to the 45-year-old central Kentucky woman now, looking back on her April 14 arrest in Mercer County. She says there may have even been value to being in jail — but “not for as long a period as I was.”

Stinnett had no money when she was arrested, but she was given a $10,000, 10-percent bond. That meant she had to come up with $1,000 to get out of jail.

“I told them that I could not come up with the bond money and if I could not go back to work, I would lose everything,” Stinnett said.

Stinnett said she wasn’t a risk to flee if released, and as for anything in her past — “I’ve had a few minor hiccups but nothing serious ever.”

Mercer County court records show Stinnett was charged with a non-violent crime. She was appointed a public defender on May 8, about three and half weeks after she was arrested. Her bond was lowered that same day — she only needed $500 to get out jail. But it was still more than she had.

Fifty-nine days after she had been arrested, Stinnett entered a guilty plea and was released from the Boyle County Detention Center on a non-financial bond, according to court records. Her case isn’t over yet — formal sentencing is scheduled for July 17.

Stinnett, who lives in Lexington, said she is now homeless. She said her situation is a tough one to be in, but she is fortunate she doesn’t have kids or things could be a lot worse.

“I’ve lost everything,” she said. “I had a full-time job — I had a good job. I worked 50 hours a week. … My boss said if you had gotten out sooner, you could have had your job.”

Stinnett’s experience may not be an outlier. Defendants in Boyle and Mercer counties have the lowest chance in the state to get out of jail without paying money, based on a statistical report recently produced by the Administrative Office of the Courts Department of Shared Services.

Getting out costs money

According to the report, statewide, defendants were offered a non-financial bond about 39 percent of the time in 2017. That’s about four out of every 10 Kentucky defendants that can leave jail without paying money.

In Boyle County, that rate is about 4 percent (about one in 25 defendants); in Mercer, it’s 7 percent (about one in 14 defendants).

The report analyzes data from Kentucky’s Department of Pretrial Services for all cases in the state between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2017. It breaks cases down by whether defendants were given no bond, a financial bond or a non-financial bond — or were let go under “administrative release.”

Defendants with low-level misdemeanors can be given administrative release by Pretrial Services before a judge reviews the case; those cases were not counted when the report determined how often defendants got non-financial bonds. In all other cases, a judge set the bond for the case.

Defendants are often given no bond (they must stay in jail) in serious cases where murder or rape is alleged, or if a defendant is considered a threat to public safety or a flight risk.

Non-financial bonds include “ROR” bonds, when someone is released on their own recognizance; and unsecured bonds, when the defendant only owes money if they fail to appear in court.

Financial bonds require defendants to pay some amount of money up front — a 10-percent bond requires 10 percent of the total bond amount; a cash bond requires the full bond amount to be paid; property bonds are paid using the value of a home, for example.

Statewide, judges set financial bonds for defendants about 49 percent of the time in 2017, according to the report. In Boyle County, judges gave defendants financial bonds about 90.6 percent of the time; in Mercer it was about 88.5 percent of the time.

Out of 1,855 cases with bonds set by judges in Boyle County, only 71 were given non-financial bonds, according to the report’s data. Out of Mercer’s matching 777 cases, 55 received non-financial bonds.

‘It might as well be $1 million’

“My reaction to the report … was just great sadness that I didn’t know it was that bad,” said Jessica Buck, directing attorney for the Department of Public Advocacy’s Danville office. “I knew it was bad — that we have a lot of people incarcerated who are presumed innocent of the crimes with which they are charged, and they’re still sitting in jail. But to see 4 percent and 7 percent — I didn’t know it was that bad.”

Buck has eight years of experience as a public defender. She took over leadership of the Danville public defender’s office in May. She was careful to note she doesn’t speak for the Department of Public Advocacy. “I speak for our clients in this office, my little corner.”

Buck said she has had clients who had their bond reduced to $500 or $300, which might not seem bad for someone with money in their bank account. But “for my clients, it might as well be $1 million.”

Buck said having been in Danville for less than two months, she hasn’t seen a lot of cases in the local system. But throughout her career, she has seen defendants’ lives impacted in devastating ways when they are stuck in jail and can’t pay to get out.

“I’ve certainly had clients who were taken into custody and their children were taken away; clients who are taken into custody and they have lost their jobs, and then they lose their homes; clients who have lost their jobs and they owe child support, and then they fall behind on their child support,” which can then lead to additional criminal charges, she said.

Buck said one interaction in the criminal justice system often leads to another: Someone may lose their job because they couldn’t get out of jail, so they have to find a new job. They have to drive to job interviews, but can’t yet afford car insurance. Then they get pulled over and get in trouble again.

“It’s just this sad cycle that goes on and on and on.”

That’s why Buck points to “people much smarter than I” who have come up with initiatives like the 3DaysCount campaign.

3DaysCount aims to reduce unnecessary arrests, find alternatives to financial bonds and restrict pretrial detention to those people who “pose unmanageable risk to public safety or of flight,” according to a news release.

Kentucky is on-board with the 3DaysCount campaign — Kentucky Supreme Court Chief Justice John D. Minton Jr. announced in early June the state would be partnering with 3DaysCount and the organization running it, the Pretrial Justice Institute.

“There’s a growing call for reform against financial bail, which can penalize the poor,” Minton said at a press conference. “Kentucky Pretrial Services is joining the wave of pretrial justice reform, which is propelling changes to bail systems across the country. … As part of 3DaysCount, Kentucky will have access to national best practices and the support of the Pretrial Justice Institute as we work to educate the judiciary, law enforcement and the public about the importance of pretrial reform.”

According to the news release, “3DaysCount is based on the premise that even three days in jail can leave many people less likely to appear in court and more likely to commit new crimes because of the stress incarceration places on jobs, housing and family connections, and that commonsense solutions can lead to better outcomes, enhanced public safety and more effective use of public resources.”

“Nearly half a million legally innocent people are held in U.S. jails every day at an aggregate annual cost to taxpayers of nearly $14 billion,” according to the release. “Most of these men and women could be released to await trial in the community and be counted on to appear in court and not be arrested on new charges while their case is handled. They remain detained solely because they are unable to afford money bail.

“Letting access to money decide who gets detained before trial lets wealthier people purchase their freedom — regardless of the danger they pose to individual and community safety — while poor and working-class men and women remain in jail even if they have been arrested on low-level, non-violent charges.”

Local ‘anomaly’

The Advocate-Messenger analyzed local jail and Boyle County court records in an effort to determine how many defendants might be in the Boyle County Detention Center without the ability to pay their bonds.

The analysis was conducted on June 19 and found 158 inmates who had been booked into the jail between three and 90 days prior (March 19 to June 16). Of those inmates, 40 had pending Boyle County charges and were being held on financial bonds. Of those 40, 33 had been appointed a public defender, indicating a lack of financial means, according to court files. The other seven had no entry of appearance for an attorney in their case file yet.

Many of those being held in jail had $5,000 or $10,000 cash bonds, according to jail records. The lowest bond was $200.

The analysis did not look at Mercer County cases and did not consider what crimes defendants had been charged with.

Tara Blair, executive officer for Kentucky’s Department of Pretrial Services, said she is aware of what the data from her office shows and believes Boyle and Mercer counties are out-of-line not just with what the state is doing, but what the nation is doing.

“The trend in the nation right now is just to eliminate money from the system because of the unfairness of money bonds,” Blair said, explaining that a financial bond creates a different hurdle for someone who is poor than someone who has money. “… That’s not really equal protection under the 14th Amendment.”

Blair said in “most jurisdictions” around the U.S., judges assign financial and non-financial bonds about 50/50; in some areas it may be more like 80-percent financial and 20-percent non-financial. Nowhere else in the nation is she aware of a jurisdiction where judges use financial bonds 90 percent of the time.

“Not only jurisdictions in the state but throughout the country — there’s an anomaly there,” she said.

The trend of financial bonds in the 50th circuit and district courts (which serve Boyle and Mercer counties) stretches back beyond 2017. An earlier report from the Department of Shared Services based on the same type of data — pretrial records for all cases handled by the courts in Kentucky — found very similar rates for the years 2012-2016.

During that time period, judges in Boyle and Mercer counties gave defendants non-financial bonds about 5.6 percent and 7.8 percent of the time, respectively. Boyle and Mercer counties had the lowest rates of non-financial bonds in the state in the earlier study, as well.

‘Revolving door’ and addiction

The 50th Circuit judge is Darren Peckler; the 50th District judge is Jeff Dotson. The Advocate-Messenger provided both judges with copies of the 2017 report and requested interviews in early June. An administrative assistant in Peckler’s office said last week he had seen the report and did not want to speak to the newspaper; an administrative assistant in Dotson’s office said this week she did not know if Dotson had looked at the report nor if he wanted to comment.

Mercer County Attorney Ted Dean was also provided a copy of the report and asked if he would like to comment; he had not responded as of press time.

Boyle County Attorney Lynne Dean said she does see some advantages to the use of financial bonds in Boyle County.

“I’ve seen more people going to rehab centers,” she said. “And let’s be honest — sometimes, people don’t have that incentive to go to rehab until they’re sitting in jail and that gives them the incentive. Sometimes that works; sometimes it doesn’t.”

Dean said if more people were given non-financial bonds and got out of jail, she’s concerned “it would be more of a revolving door out at the jail” as people are released and then reoffend.

“People are already reoffending while they’re out on bond at a rate that I think is fairly alarming,” she said. “Drug addiction just has such a hold. I just see it happening again and again.”

Dean said while she doesn’t have a role in setting initial bonds, she does work with public defenders every Tuesday on making recommendations to the judge for changes in bond amounts. Often, the judge accepts those recommendations.

Dean said defendants in Boyle County can also receive a $100 credit toward their bond for every day they spend in jail, which makes it possible in some cases for someone with a $10,000, 10-percent bond (requiring $1,000 up-front) to bond out after 10 days.

The $100 per day bail credit is a requirement of state law, according to the public defender’s office.

Dean said another factor is the victims of crimes, who often don’t want to see the person accused of the crime released.

“Sometimes, people forget or don’t think about the victims,” she said. “And that is an area that I experience that others don’t always see.”

Some victims are “legitimately fearful” that if someone gets out of jail, they will come after them; others are afraid if a defendant is released, they’ll hurt themselves, Dean said.

“I’ve had mommas come to me crying, saying, ‘If you let him out, he’s going to die,’” she said. “I feel like those victims need a voice; they need to be heard. And those family members need to be heard. I won’t necessarily say that they always impact the outcome. But if I’m thinking about doing a $10,000, 10-percent (bond) with drug screens and I have a momma coming in and saying, ‘He’s going to die; I’ve got him a rehab bed,’ I’m probably going to try to do the rehab option.”

How it works

When someone is arrested for an alleged crime and booked into a jail, a Pretrial Services officer conducts a risk assessment, said Blair with Pretrial Services.

The risk assessments are created using the Public Safety Assessment created by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation — an assessment based on years of research and evidence that has been validated using data from more than 2 million cases in Kentucky, Blair said. The same assessment has been statistically validated in other jurisdictions, she added.

Defendants with low or moderate risk assessments are theoretically good candidates for non-financial bonds, but other factors are considered, too. The decision is ultimately left to the judge on the case.

“It’s just a tool,” she said. “It can’t really predict human behavior, but it’s one thing the judge can consider.”

Each risk assessment includes an extensive check of that person’s background, including Kentucky and nationwide criminal history checks, prior convictions and prior instances of failure to appear.

Every defendant is assessed for a likelihood of failure to reappear and a likelihood to reoffend if released. Those two scores are used to determine the risk of releasing the defendant.

Blair said the defendant’s risk level and what the charge is determines whether or not Pretrial Services can grant administrative release. In general, people charged with low-level misdemeanors can be eligible for administrative release, but there are numerous exceptions, such as a charge of driving under the influence, having another pending criminal case, or a prior failure to appear.

For those who don’t qualify for administrative release, a judge must set the initial bond.

Blair said in the 50th District Court, Pretrial Services calls Judge Dotson once or twice a day to set initial bonds (a Supreme Court ruling requires a bond be set within 24 hours of arrest). Dotson is given information on each case from the police citation; the defendant’s risk score; and any criminal history. Then Dotson sets a bond, she said.

In the 50th Circuit Court, Blair said Judge Peckler “doesn’t take our calls.” Instead, Pretrial Services sends written reports to Peckler, who reviews them “when he wants” and sets a bond. There is no 24-hour requirement at the circuit level, which deals with people who have been indicted, Blair said.

Public defender Buck said if a defendant is assessed as a low or moderate risk, they’re supposed to be eligible for an unsecured bond or to be released on their own recognizance.

Kentucky’s Rules of Criminal Procedure state that, “A defendant shall be released on personal recognizance or upon an unsecured bail bond unless the court determines, in the exercise of its discretion, that such release will not reasonably assure the appearance of the defendant as required. In the exercise of such discretion the court shall give due consideration to recommendations of the local pretrial services agency when made as authorized by order of the Supreme Court.”

The rules go on to state that if releasing someone on their own recognizance or with an unsecured bond is “not deemed sufficient … the court shall impose the least onerous conditions reasonably likely to insure the defendant’s appearance as required.”

If a non-financial bond and reasonable conditions — such as travel restrictions or supervision — are still not enough, courts are then authorized to set a financial bail. The amount of such a bail “shall not be oppressive and shall be commensurate with the gravity of the offense charged,” according to the rules.

“In determining such amount, the court shall consider the defendant’s past criminal acts, if any, the defendant’s reasonably anticipated conduct if released and the defendant’s financial ability to give bail.”

They’re coming back

“I think that community safety is always a valid reason for using a financial bond — I agree with that reason,” Buck said. “However, when the scientifically validated, evidence-based risk assessment says that this person is not a danger to the community,” that should carry weight in determining bond.

“The individuals that I’m sitting here and saying should be released on non-financial conditions are not cases where the crimes are violent,” she said. “We’re not talking about murder and rape and things like that.”

In fact, keeping people in jail could have a negative impact on the community, she said.

“We somehow think that putting people in custody pre-trial makes the community safer — that the victims are protected, that the community is protected. But I don’t see evidence that that is actually true,” she said. “… No one is advocating to just let everyone go free. But when you’re talking about low-level (crimes), the best way to keep our community safe is to help people learn how to live in the community, not remove them from the community for a period of time and then shove them back in.”

Buck said many people incarcerated for low-level offenses will be “returning to our community in the near future.”

“Offering them help and telling them they are a valued and important part of the community … is the better way to keep our community safe.”

Ephraim Helton, a private Danville attorney, said his clients usually have enough money to pay their bonds and get out of jail. But he said he does see more non-financial bonds offered in other jurisdictions he works in. Boyle and Mercer’s judges also place conditions of release such as drug screening on defendants much more often than other judges, Helton said.

“I do not see it in other counties. I do not see (Pretrial Services) being involved in people’s lives in other counties as extensively as they are here. And I think that also is a part of what impacts our jail and how many people we have.”

Helton said he believes placing conditions on defendants makes it more likely one mistake or even a court error could result in them having their bond revoked and landing them back in jail.

Helton said he has seen clients that couldn’t get out of jail as quickly as they hoped and they wind up losing their job.

Like Buck, Helton said he sees a spiral that forms: “That puts you in a situation I think that you’re more likely to commit another crime. You can’t go back to the stability you had.”

Helton noted he doesn’t see that happen very often with his clients. He said he believes every judge is doing what they believe will be best for the community when they set bonds.

“At the end of the day, every judge out there thinks they’re doing what’s appropriate. They’re trying to do the best they can and it’s their vision of how their community should be. That’s part of being a judge,” he said. “I think our judges try to do the best they can. I don’t always agree with them, but it’s not as a result of being mean-spirited or trying to make life onerous on people that are arrested. In their view, they’re trying to make these people that have violated the law get on the right track.”

‘A huge toll to pay’

When it comes to solutions, Buck said she thinks it would make a big difference if judges would put more trust in Pretrial Services’ risk assessments.

“I do have faith in evidence-based practices,” she said. “To give faith in that instrument and say, ‘this evidence says that this person is not likely to commit another crime and is likely to show back up for court’ — if we could do that, I think that would be a huge start.”

Helton said if he were a judge, he would definitely remain strict on bonds for “frequent fliers” and more serious offenses. But for cases involving substance abuse — “those people need treatment as opposed to incarceration. So that’s probably where I would break down a little bit different from what I see going on today.”

Blair with Pretrial Services said some jurisdictions such as Washington, D.C., and New Jersey have actually eliminated financial bonds altogether. She said she would “100 percent” like to see Kentucky do away with financial bonds, as well.

Boyle County Attorney Dean acknowledged the Boyle County Detention Center is overcrowded — something public officials have been working to find solutions to for some time. She is skeptical that increasing the number of non-financial bonds could solve the jail’s problems, but said a change in bonds could be one piece of the puzzle.

The Boyle-Mercer Joint Jail Committee, which oversees the jail’s operations, expects to receive findings from a comprehensive jail study as soon as July. That report could include recommendations for substantial changes to how the local criminal justice system operates.

“I think that everyone involved in the Boyle County court system right now is open to (changes), and that’s one thing that makes me extremely happy,” she said. “I feel like everyone pretty much is open to new ideas and ways that we could be better, ways that we could change things.”

Stinnett, who spent 59 days in jail, said as bad as her situation became, she saw others while she was in jail who were worse off.

“They were losing their children, husbands, homes and jobs,” she said. “… That’s a huge toll to pay.”

Stinnett said her time in jail has “affected me in every way shape and form — I will never be the same person.”

There’s a possibility of her having to pay restitution in her case; she’s unsure how she could afford that now that she has no job and no home. But, she said, she intends to overcome those obstacles somehow.

“I don’t want this to determine who I am. I am a strong person, and I will bounce back regardless.”