Overdose down in Boyle County in 2017: Fewer died locally, but statewide, deaths went up 11 percent

Published 6:05 am Thursday, August 9, 2018

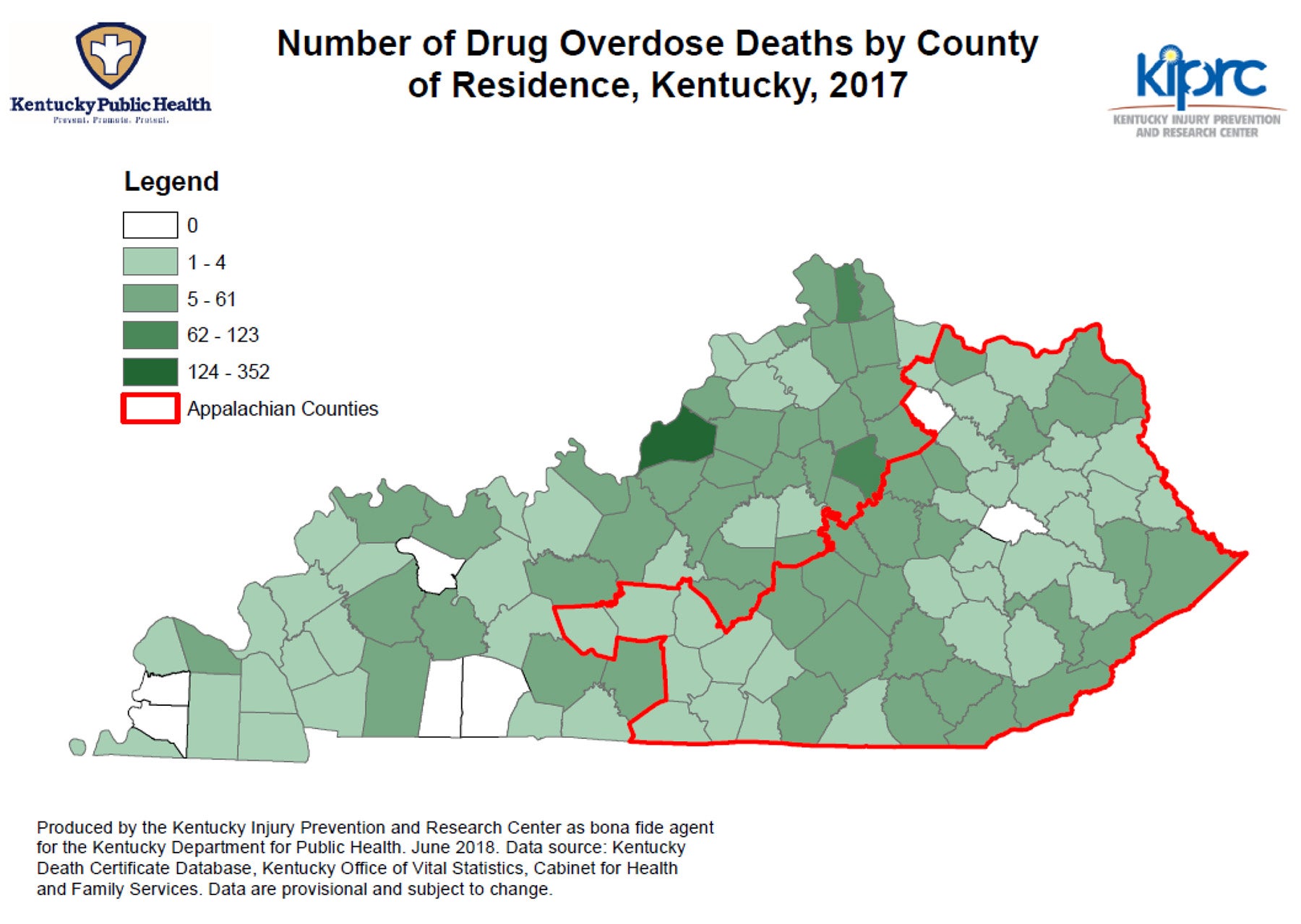

- Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy A graphic from the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy shows county-by-county numbers of drug overdose deaths from 2017. The red outline denotes counties considered to be part of Appalachia.

Boyle County saw 11 fewer overdoses in 2017 than it did in 2016, according to the Kentucky Overdose Fatality Report compiled by the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy.

While 19 people died from drug overdoses in Boyle in 2016, there were eight overdose deaths in 2017, said Kathy Miles, coordinator for the local Agency for Substance Abuse Policy (ASAP).

“I’m cautiously optimistic,” Miles said. “Yes, it is a good decrease, but because the state’s numbers are up and because we have counties as close to us as Jessamine and Fayette that look pretty bad, we don’t want to say, ‘oh, we can let up …’ I think we have to continue” efforts to lower overdose deaths.

Statewide, overdose deaths went from 1,404 in 2016 to 1,565 in 2017 — an 11.4-percent increase. The report also found:

• People between the ages of 35 and 44 suffered the most overdose deaths (353), followed by ages 25-34 (295 deaths) and ages 45-54 (291 deaths).

• About 22 percent of overdose deaths involved heroin, which is down from 34 percent in 2016.

• The extremely powerful opiate fentanyl was detected in more than half of all overdose deaths in the state.

• Jefferson County (Louisville) saw the largest increase in overdose deaths, with 62 more than in 2016, followed by Fayette (49 more), Campbell (26 more) and Kenton (17 more).

• The top five counties for overdoses per capita were Kenton (one in 69.5 people), Campbell (one in 66), Boyd (one in 64.6), Mason (one in 58.2) and Jessamine (one in 56.5).

Boyle County’s population was too small for an accurate per capita rate, according to the report. Of Boyle’s eight overdose deaths, one to four involved fentanyl and none involved heroin.

Positives in Boyle

Miles said there are numerous efforts by government, law enforcement, churches and community members that have hopefully helped with Boyle County’s drug problems and may have led to fewer overdose deaths in 2017. But she cautioned no one can say for certain why Boyle’s number dropped.

“We can talk about correlation, but we can’t talk about causation,” she said. “I hope that EMS’ response and so many people talking about treatment and giving out naloxone (an overdose antidote) … I sure hope those make a difference.”

Miles listed the increasing use and acceptance of naloxone first when recounting the ways in which Boyle County has improved its response to the drug epidemic in recent years.

It’s not just EMS or law enforcement who should keep the drug on-hand and know how to use it; family members of people who use illegal or prescription opioids and those who know someone in recovery from addiction should all be prepared, she said.

In Boyle County, more and more people are getting training on how to use the drug to bring back someone who is experiencing an overdose, but more can still be done, she said.

“Boyle has some more remote parts of the county and we need to do a better job … of reaching further out into the county and doing training,” she said, explaining that when an overdose occurs in a rural area, EMS may not be able to reach the person in time. In those cases, having a friend or family member capable of administering naloxone is essential to save a life.

Boyle County has also done a good job of getting word out that treatment is available. More people are learning that insurance will cover treatment for drug addiction. And thanks to local churches, ASAP even has some funds available to help pay for people to get treatment, she said.

Boyle County Health Department Director Brent Blevins said he thinks Boyle County has a large number of people from different backgrounds working together through groups like ASAP to make a difference. It’s routine for elected officials to attend meetings and support improvements in drug policy, he added.

“I think that’s probably pretty rare for some communities to have that type of support,” he said. “… I think that’s maybe related to the drop in (overdose death) cases that we’re seeing.”

Miles also listed the Shepherd’s House treatment program for former Boyle County inmates and expansion of Celebrate Recovery support meetings among many other things having positive effects.

Syringe exchange

Boyle County’s syringe exchange program is also a public health benefit, even if its impact on overdose deaths is indirect, Miles said.

Blevins said since the syringe exchange began in early 2017, it’s given out about 12,000 clean needles to injection drug users and taken around 6,000 dirty needles off the streets. The difference is because the first time a client comes to the exchange, they receive 30 clean needles, he explained.

The program has seen clients from around 10 different zip codes; there are anywhere from two to 15 people who use the exchange each week, he said.

There are drug users who come to the exchange, which provides information on drug treatment, and then report that they have sought treatment, Blevins said. They also get people who report they’ve been in treatment before and know they need to go back.

“Some people would probably look at that as a negative — ‘Oh, they’ve been through treatment before,’” Blevins said. “… Sometimes it just takes four, five, six, times to get them off of whatever they’re using.”

‘Keep paying attention’

Miles said it’s good to celebrate Boyle County’s successes, especially when someone is able to stop using drugs and enter recovery. It’s also important not to gloss over the pain each overdose causes for friends and family of the person who died.

Boyle County can still do more to bring its overdose deaths down to zero, she said. That includes something ASAP has identified as a “huge need:” an emergency housing crisis unit that could provide a short-term living space for someone who wants to go to treatment but must wait for a bed to become available.

Such a facility could be staffed by a case manager, who could help clients plan for the supports they need as they recover, housing they’ll need when they get out of treatment, vocational rehab so they can get a job and more.

“We need that not just for people with substance-use disorders, but we need that for people with a mental health crisis,” she said.

An initial problem, obviously, is the cost. Miles said the initial expense of setting up a facility is a big hurdle. Funding could come from a private company expecting to recoup its expenses down the road; a local government; or a federal grant.

Then there’s the ongoing cost of running such a facility.

“It’s not like paying for ongoing treatment; it’s paying for the crisis,” Miles said. “And whether that could be billed to insurance or Medicaid is a question. And if it can’t be, then the question is, ‘Who’s going to pay for it?’”

Miles said such a facility may not happen right away, but it’s good that ASAP has identified it as a need in the community.

“It’s easy to be discouraged. But this public health crisis of addiction didn’t happen overnight and anybody who thinks we could resolve it overnight just doesn’t understand,” she said. “We have to pay attention and we have to take it seriously, but we can’t get discouraged. We have to keep paying attention to what does work. Celebrate the successes and grieve the losses.”

Regional overdose deaths

According to the 2017 Kentucky Overdose Fatality Report, area counties saw the following numbers of overdose deaths:

• Boyle County: 8

• Casey County: 6

• Garrard County: 5

• Lincoln County: 7

• Mercer County: less than 5

VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITY

ASAP Coordinator Kathy Miles said one way community members can help with efforts to combat drug addiction is by volunteering to be mentors for high school students through the Hope Network’s mentoring program, which aims to help prevent kids from beginning to use drugs. Volunteers go through one two-and-a-half hour training and then get matched with students in the Danville and Boyle County school systems. Volunteers spend about an hour a week with their students, providing them with a positive, caring adult role model. Anyone interested in being a mentor can contact James Hunn at circleofhope.danvky@gmail.com or Jason Kilby at pastorjasonkilby@gmail.com.