A missing piece? Certified drug court for Boyle, Mercer could help reduce jail population

Published 6:02 am Friday, October 5, 2018

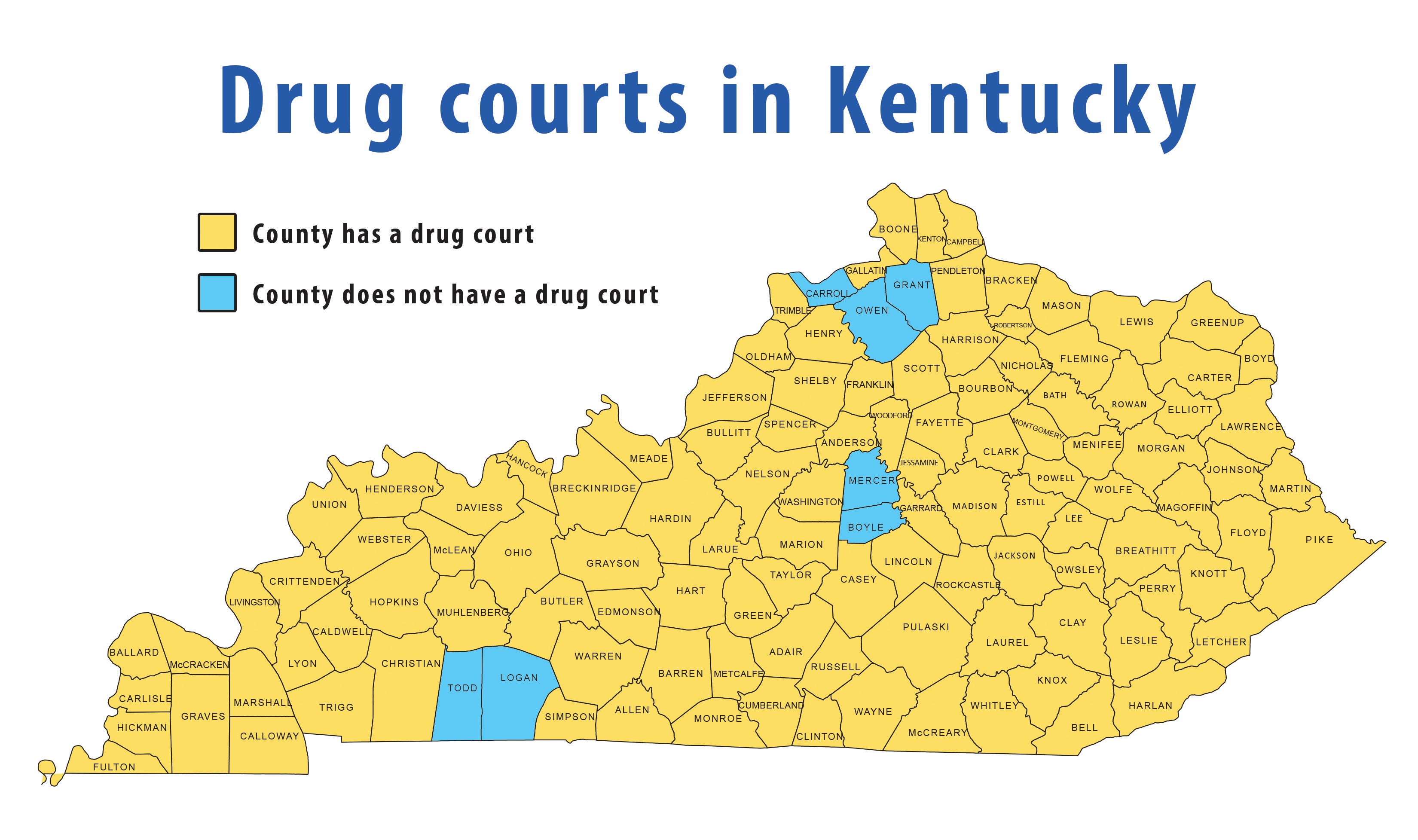

- Map by Kentucky Administrative Office of the Courts/Graphic by Ben Kleppinger “Since the Kentucky Court of Justice began implementing Drug Court in 1996, thousands of participants have successfully completed the program,” according to the Kentucky Court of Justice. “Instead of spending time in jail, eligible participants complete a substance abuse program supervised by a judge.” Boyle and Mercer counties, which are served by Kentucky’s 50th Circuit and District courts, are among seven out of the state’s 120 counties that do not have a certified drug court. A report commissioned by the two counties has recommended changing that.

Boyle County has a drug court in “name only,” according to a draft study of the jail and criminal justice system in Boyle and Mercer counties.

While there is something called a drug court run by Boyle County Circuit Court Judge Darren Peckler, it “does not follow Kentucky’s specified model, which contains ’10 key components,'” according to chapter three of the 100-plus-page comprehensive report commissioned by Boyle and Mercer counties’ fiscal courts as they seek to rein in their inmate population and jail budget.

Boyle and Mercer counties are in fact two of only seven counties in the state that do not have a drug court approved by the state Administrative Office of the Courts, according to information from the Kentucky Court of Justice. The other counties are Carroll, Owen and Grant in northern Kentucky; and Todd and Logan in southwestern Kentucky.

The report’s chapter-three analysis looks specifically at alternatives to incarceration and makes six recommendations, including two concerning creation of a certified drug court.

The Kentucky Drug Court system was created in 1996 “to assist individuals who have entered the criminal justice system as a result of drug use or drug-related criminal activity and are choosing to achieve and maintain recovery,” according to the Kentucky Court of Justice. “… Today there is irrefutable evidence that Drug Court is achieving what it set out to do — substantially reduce drug use and criminal behavior in drug-addicted offenders. For more than 20 years, the program’s solid track record has convinced leaders in state government, along with local judges, prosecutors and treatment providers, that Drug Court is an essential part of the Kentucky court system.”

Certified drug courts use a “non-adversarial approach” with defendants, where “prosecutors and defense attorneys collaborate on program design and implementation,” according to the report. Eligible defendants are identified based on criteria developed by a local “drug court team” made up of representatives from the criminal justice system and community leaders.

Drug courts provide “comprehensive” treatment and rehabilitation services for defendants, whose abstinence from alcohol or drugs is monitored by “frequent and random testing.” Drug courts are further improved by “ongoing judicial interaction” with defendants on a regular basis and my monitoring and evaluating how well the court is achieving its goals, according to the report.

In the “drug court” run in Boyle County, “participants attend court one time per month but are not mandated in every case to attend treatment,” the report states. “… During the interviews of attorneys in Boyle and Mercer counties, a frequently heard theme was the existence of a large number of drug-involved defendants. An estimate of the number of persons who could be accommodated by a drug court has not been estimated and will likely not be estimated without significant effort.”

The consultants working for Brandstetter Carroll who developed the report wrote that their examination was hobbled somewhat by a lack of participation from state agencies and the local court system.

“… the chief judge of the 50th Circuit (Peckler) … issued an order that prohibited members of the court from talking to the consultants. Thus, the consultants had to gather information in an indirect manner through interviews of attorneys, collection and analysis of jail data, and researching operations and relevant statutes provided through the internet,” the report states.

When it comes to analyzing management of probation and parole cases to see how that might affect the local jail population, “unfortunately, requests for information were not answered by the Kentucky Department of Corrections and Probation and Parole, which would have enabled the consultant to determine the impact their department has on the Boyle/Mercer county jail population,” the report reads.

Peckler has not responded to requests from The Advocate-Messenger for comment on how he operates the 50th Circuit Court.

A request for comment made at the state Probation and Parole office in Danville was referred to Kristie Willard, a supervisor who represents the Department of Corrections on the local Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, which was formed as part of the consultants’ study.

A request for comment to Willard was answered by Lisa Lamb, director of communications for the Department of Corrections.

“We haven’t had an opportunity to review the draft jail study,” Lamb wrote. “… The Department of Corrections staff will continue to provide county officials with any information we can to aid them in making an informed decision on how to proceed.”

Asked about the study claiming the Department of Corrections and Probation and Parole did not respond to consultants’ requests, Lamb wrote, “When we received their requests at the central office level, which is the appropriate location for such requests, we supplied them with information to the best of our ability. It may have taken some time due to the volume of requests we receive. Also, we indicated that we are only able to respond to data-related questions, and not able to comment on process related inquiries.”

Even without all the data that was wanted, information that was gathered for the report “suggests that probation and related operations substantially affect size of the jail population,” according to the report.

Attorneys interviewed for the report said there are “a large number of persons who violated probation and were placed in jail by the court.” With probation violation hearings held once a month, “it takes an average of 60 days to resolve a technical violation by the court,” the report states.

The report recommends the local courts “refine” the use of “graduated sanctions” instead of re-jailing so many people who violate conditions of their release. But it also notes that Peckler “does not favor the use of standard practices for dealing with low-level probation violations, such as graduated sanctions, or with treatment aimed at reducing recidivism …”

Graduated sanctions can include electronic monitoring, drug or alcohol testing, “reporting centers,” “rehabilitative interventions,” community service and residential treatment, among many other options.

“Given the lack of communication with probation authorities or the court, it is unknown about the court’s policy on lower-level violations or the judges’ manner of dealing with recommendations by probation officers about responses to violations,” the report states.

The report also recommends use of “discretionary detention” when someone violated a probation or parole condition. Discretionary detention, when allowed by judges, lets defendants be jailed for 10-30 days for violating conditions of their release instead of being charged with a new crime — contempt of court, in many cases — and starting a whole new case against them.

“Importantly, the use of discretionary detention would avoid the charging of a probationer with a new offense, such as contempt of court or revoking probation and remanding the individual to jail,” the report states. “Unfortunately, the consultant was unable to obtain a clear description of the court’s policy and practices in this area. Given the large number of contempt of court offenses found in the survey of inmates exiting jail … the consultant suspects that the application of discretionary detention may not be a clearly defined practice by the court.”

Of 334 inmate cases studied for the report, 18 percent had a pending charge for contempt of court, while 12 percent had charges for failure to appear. The “predominant reasons” for the contempt of court charges were probation violations, bond condition violations, failure to appear and failure to pay a fine or court costs.

The report notes multiple side effects of charging so many people with contempt of court:

• “… it is possible that a defendant with stacked penalties could spend more than a year in jail;”

• “When a defendant is charged with an additional crime, he or she must traverse the court system again (from the beginning);”

• “Recycling back to the beginning with a new charge increases the workload of all court-related players and, in some instances, can slow the speed of overall case processing;” and

• “The jail population is bloated with defendants who have a second bond imposed on top of the original charge.”

In order to solve the contempt-of-court problem, the report states, “A solution would be for the judiciary to consider issuing a … summons for the defendant to appear in court for the purpose of addressing the violation instead of filing a new charge. Many times, the behavior of the individual could be handled without incarceration. The secondary benefit would be reduction of unnecessary use of jail beds and (a) decrease (in) the workload of the judge, attorneys, pretrial staff, probation, clerks and other persons involved in criminal case processing.”