First of February brought freedom for Boyle WWII vet

Published 6:57 am Friday, November 9, 2018

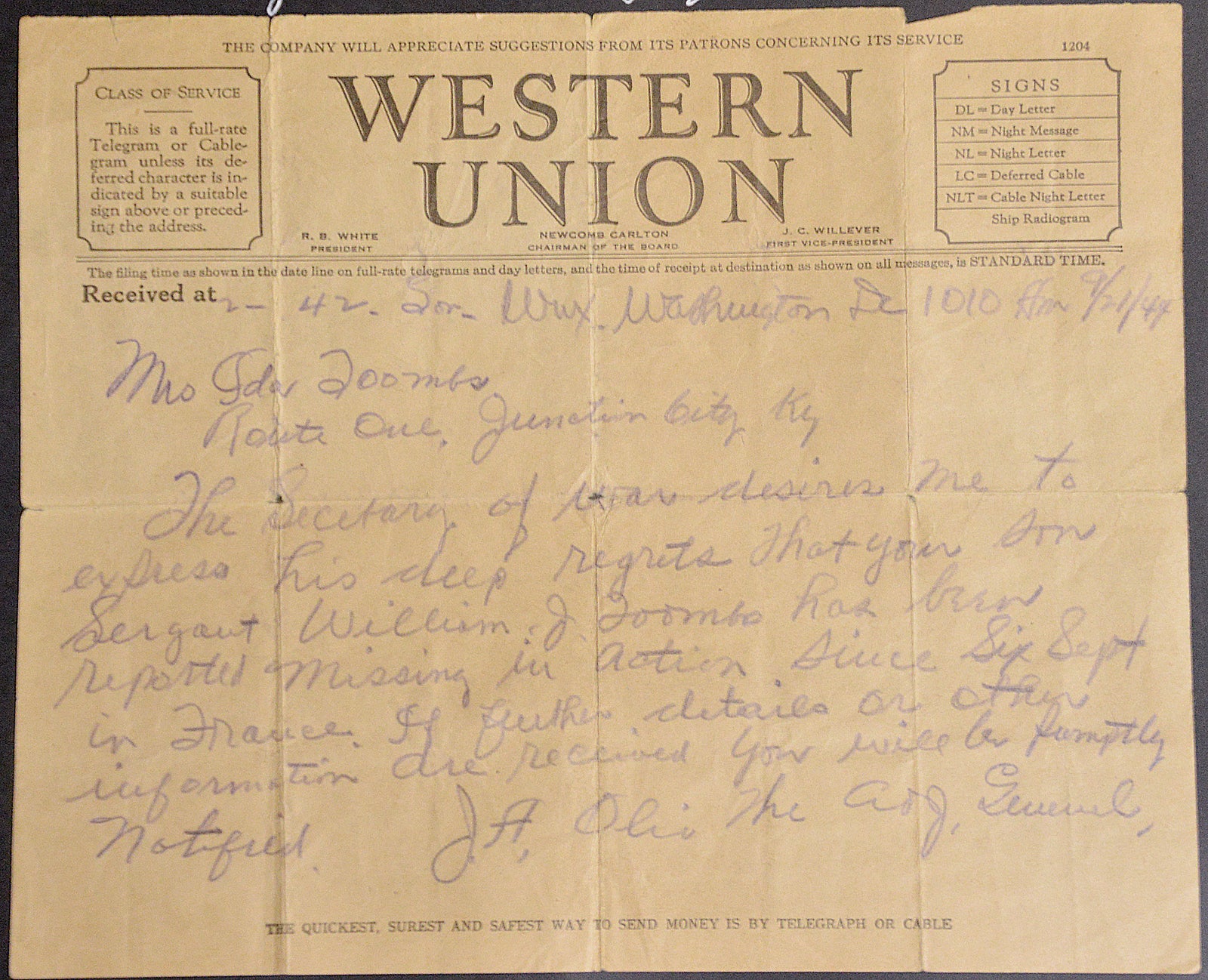

- Robin Hart/robin.hart@amnews.com Mrs. Ida Toombs, of Route One, Junction City, received this telegram reporting that her son, William J. Toombs was missing in action in 1944.

Roberta Toombs Trayner fondly remembers her daddy, J.W. Toombs, especially on Veterans Day. Clutching a large scrapbook filled with her father’s World War II memorabilia, the Danville resident gently pulled out a large official Army portrait of her daddy to be copied for The Advocate-Messenger’s annual Veterans Day special section.

“He looks so sad,” Roberta said.

Photos contributed W.J. Toombs was drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II. When filling out the paperwork, he was told he couldn’t use only his initials, even though they were the only first name listed on his birth certificate, his daughter Roberta Trayner said. That’s when he decided just to say his name was William.

J.W. was just 21 years old, married and was expecting his first child when he was drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II, Roberta said softly. And little did he know that he would also become a prisoner of war.

Sitting at a table, Roberta opened the book and shared many of her father’s war memorabilia. His Army cap is attached to the inside front cover. The pages contain his baby photograph, a copy of his birth certificate, photos of his wife, Mary Elizabeth and daughter Roberta. There are also badges he earned for being a shooting expert, his sergeant stripes and telegrams sent to his family when he was listed as missing in action.

“Daddy did not talk often about his experiences in the Army and of being a prisoner of war. I believe some memories of the experiences were very painful for him,” Roberta wrote on a page of the scrapbook.

“Every year around the first of February, he would reminisce and talk because February first was a happy day for him. On that day in 1945, it was his 24th birthday, his first full day of freedom from the German prison camp and his second daughter, Billie, my only sister, was born,” Roberta wrote.

Also included in the scrapbook are pages Roberta wrote down on the afternoon of Sunday, Feb. 7, 1999, while talking with her father at his home, about some of his WWII experiences. He had a stroke just three days later and died on Feb. 12, 1999.

“I never had the opportunity to discuss his life again,” she wrote. But she was very thankful that she followed a co-worker’s advice and wrote down her daddy’s rmemories about the war and being a prisoner.

J.W. was born on Feb. 1, 1921 in his family’s home on White Oak Road in Junction City.

He loved working on the farm, especially with the cattle, Roberta said. One of his favorite things to do was go to the livestock sales at the stockyard. And that’s where he learned the skill of “pen hooking” from his father, she said, laughing. He would buy a farmer’s cattle before they were unloaded at the sale, then turn around and sell them at the sale — hopefully, for a small profit.

J.W. attended Junction City School and dropped out of high school after the 10th grade to work on his family’s farm. He married soon after and was drafted in 1941. By the time he was shipped off on July 2, 1942, the young couple was expecting their first child.

Roberta also has an audio tape of her father talking about being in World War II, which was recorded in 1992. In the tape, Toombs said from here, the Army took him to Tennessee, then to Kansas, Arizona and New Jersey before shipping him off overseas to Scotland, England, France and Germany.

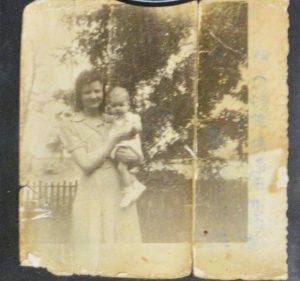

W.J. Toombs kept this small photograph of his wife, Mary Elizabeth and his daughter, Roberta, folded in his mud-soaked wallet while a prisoner in a German camp.

Toombs was a sergeant in charge of the machine guns, Roberta wrote. He could also take apart and reassemble a rifle blindfolded and earned three badges for marksmanship.

On the day he was captured, Toombs had orders to cross the Moselle River in northern France. “They spread out their guns,” Roberta said, but she doesn’t know what that means and wishes she had asked him.

The Germans had destroyed the bridge, so soldiers crossed the river in several small boats, but only the first and third boats got to shore safely. “Daddy was on the third boat.”

Some of their boats were blown up, a few got downstream, but many soldiers were shot and drowned.

The 11 surviving soldiers fought with what little ammunition they had and when their supply was used up, the Germans closed in and captured them.

The prisoners were told to empty their pockets before being sent to prison camp, Roberta said. Anything of value, like watches, were taken.

She then turned a page in the thick book. There she pointed to a simple band. “That was Daddy’s wedding band,” she said. It was the only thing valuable he was able to keep, because he hid it under his tongue when the Germans were searching the men.

Toombs told his daughter the train ride from France to Germany took two and a half days. They weren’t given any food or water. “Daddy said that his dad always told him that he would eat anything if he was hungry. Daddy said he knows what hunger is.”

Roberta said the prisoners would have starved to death had it not been for the Red Cross sending them food parcels occasionally. Her father and the rest of the prisoners were given only one cup of watery soup made by boiling rutabagas, she said.

When Roberta turned to another page, she pointed out a tiny calendar and a creased photo of a pretty, dark-haired young woman holding a baby with chubby cheeks — his wife, Mary Elizabeth and Roberta — that was taken while he was on leave before he returned to France and was captured.

He carried that photo in his mud-soaked wallet while imprisoned, Roberta said.

Badges belonging to W.J. Toombs of Junction City. They show he was a part of the 4th Army, 80 Division and American 28th Division in Normandy.

A 1944 pocket calendar has the days marked out from Sept. 6 when he was captured through Dec. 31. On Jan. 1, 1945, the men starting marking the days with scratches on the wall, she said.

“Daddy said that he was in prison for five months with very little to eat and no mail,” Roberta said. “The soldiers were given a card to fill out to be sent to his mother. It read, ‘Am POW somewhere in Germany, not wounded, am alright.'”

The Germans moved the prisoners further into the country, Roberta wrote in the scrapbook. Then the Russians began invading Germany and soon freed the American soldiers.

By that time, the German families had fled their homes to get away from the fighting, so the American soldiers, to celebrate their freedom on Jan. 31, 1945, slept in their beds and ate their food. “They set the table with silver, dishes and lit a candle to celebrate their freedom,” Roberta wrote that her dad said.

The only time that Toombs stole anything was when he and the other freed prisoners took bicycles the Germans had left behind and rode them out of town, Roberta wrote.

After getting out of Germany, Toombs said it took him two and a half months to get back home to Junction City. Toombs surprised his parents at their home early one morning and was told he had another baby girl, Roberta wrote.

When Roberta’s mother saw Toombs, she was holding their 10-week-old daughter, Billie. “Mother became so excited that Daddy thought she was going to drop Billie,” Roberta wrote in the scrapbook.

While Toombs was away, his wife Mary Elizabeth had begun working at Palm Beach company and bought a house on Walnut Street in West Danville for $2,700 so they’d have a place to live.

The Army allowed Toombs 60 days to be home before sending him to Florida to receive a physical and he was assigned to kitchen duties until he was discharged on Oct. 15, 1945.

Roberta said her daddy joined the Army as a private, then was promoted to private first class, then corporal. Normally a soldier had to have a high school diploma in order to be a sergeant. But Toombs was promoted to sergeant even though he only had a 10th-grade education because of his hard work.

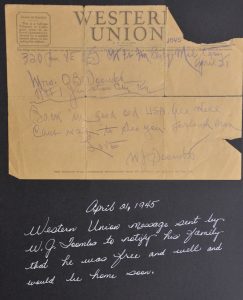

On April 21, 1945, W.J. Toombs sent this telegram to his family in Junction City saying he was free and would be home soon.

“Daddy’s pay almost doubled from $50 per month to $96 per month,” Robert said.

After returning to Boyle County, Toombs settled into family life and worked at Royal Crown Bottling Company before taking a construction job at Corning Glass. He eventually was given a full-time job at the factory as a tank operator.

“He was a hard-working and loving Daddy.”