Needle exchange program hits 2 years; director says it’s making strides and creating change

Published 8:20 pm Friday, January 11, 2019

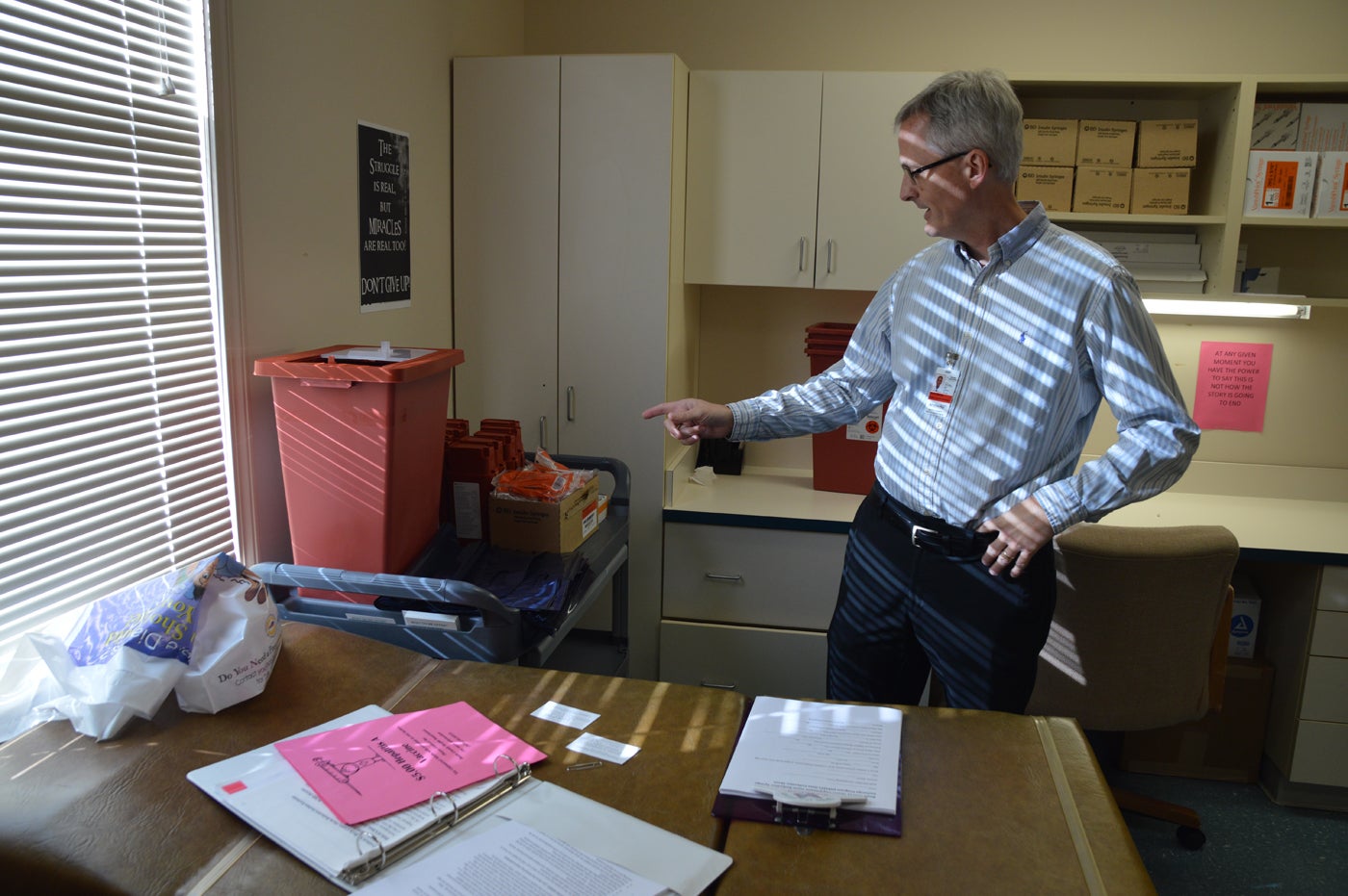

- Photo by Bobbie Curd/bobbie.curd@amnews.com Brent Blevins, standing in the needle exchange room in the back of the Boyle County Health Department, explains the contents of the cart, and how clients go through the program.

When the local needle exchange program began, it was offered 1-3 on Friday afternoons. It took the health department about six months to figure out — “This is a need, just like any other regular clinic we offer,” said Brent Blevins, public health director.

Now, the Boyle County Health Department is right at the two-year mark with the program. Something they thought would be a couple of hours a week has become routine for them. It’s come a long way — and so has the community with backing it.

Two years ago, the room was in the basement, with a camera showing the outside door.

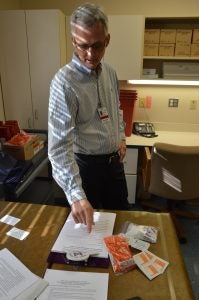

Photo by Bobbie Curd/bobbie.curd@amnews.com

Items clients of the needle exchange program are given include a pack of clean needles, a Stericup, a wound care kit and alcohol pads for sterilization.

“The first guy who came in really set the tone, I will never forget this,” Blevins said. It was a young guy; he came right up to the basement door, but just stood there.

“He said it took him a second to stand there and realize it wasn’t a setup, and he finally came in. And that was it. After that, the program took off.”

Blevins said after all of the work done to make the public aware of how the program operates — it took one person coming in, getting clean syringes and leaving without incident to get the word out.

“It took a long time for people to trust us, but they finally do,” Blevins said.

Boyle County Sheriff Derek Robbins thinks that at first, users thought law enforcement would be checking into the program in order to make arrests.

“We don’t have anything to do with that. I’ve never even talked to Brent about it. I hope everybody who uses does take advantage of the needle program — it helps prevent the spread of disease and infection … It’s a good program and we need it.”

For users to buy in, it has to be quick and simple, Blevins said. Clients are given an identifier number based on whatever name they choose to give — some use their real name, others don’t. They are not asked for identification.

“We go through a really quick form with them, we put things in the bag, and they’re usually gone.”

The exchange room — a regular exam room — is now on the main floor in the back of the health department, with an easier entrance and exit so participants don’t have to walk past many people. Blevins opened up the drawer on a tall cart.

“We give them a bleach bottle, which essentially says look, if you’re getting ready to use a dirty needle, at least put it down in the bleach, pull some through it, clean it the best you can and wash it with water before you use it,” Blevins said.

There’s a small bag containing wound care items, like Neosporin and Band-Aids so track marks can be kept clean to avoid infection.

“We give them a little cooker cup. That was different, at first.” Blevins pulled out the Stericup for users to put substance in to melt down.

“Otherwise, they’ll use a pop can off the side of the road or a dirty spoon,” he said. “If that helps you, great. Let’s make this as clean as possible, use that instead of that dirty spoon.” There’s a small cotton pad included, used like a filter in some cases, to stick the needle through while drawing the drug into the syringe.

Photo by Bobbie Curd/bobbie.curd@amnews.com

Brent Blevins says the needle exchange program measures successes in different ways. “If they return, that’s a success.”

Condoms are also offered, and staff talks safe sex with users as much as they can. Clean tourniquets, used to tie the arm off and stop blood flow to expose a vein, are provided.

“Interestingly enough, we now have some people who have been identified with latex allergies due to the tourniquets. They’ll say they can’t use those.”

Although most come in and out quickly, some will talk for a while. They’ll sit down, tell them about how they got to where they are; about their family life. How they ended up in jail. Maybe a small glimpse into how they get their drugs is shared, but not often — they’re very secretive about that.

“It’s disheartening and sad, in a way. But I’m glad they can talk about it to us. We have a resource list we give them, it lists inpatient and outpatient services, for example …” which he finds positive. “For them to be somewhat interested in seeing those options, maybe they’re starting to think coming into the health department and exchanging dirty needles for clean ones isn’t what I want to be doing in my life.”

Blevins said Vicki Vernon has been imperative to the program. “Clients really trust her. Since she’s a nurse practitioner, they can also talk to her about medical questions, too. What will be two minutes for me with a person will end up being several minutes, if she helps them. They talk to her.”

For the very first visit, they get up to 30 clean needles without bringing any dirty ones in. Then, they get the same amount they bring in dirty to exchange, up to 30 needles once a week.

“We look at success in this program differently. If they continue to come back, we consider that a success. If they start bringing people with them or referring people, that’s a success.”

Many go to different counties’ programs than where they live. Although 40422 is the most used zip code in the program, last time they counted they had up to 17 different ones.

If participants need further services, they have to go back up front and have a chart started on them, like any other health department patient.

In two years, the program has seen 182 different people, representing 603 total visits. Over 8,500 dirty needles have been disposed of, and 16,000 clean needles given out. Since it began, Blevins said there’s been a decrease in people reporting seeing needles on the ground.

“They’re still out there, but don’t seem to be as common,” he said. At one point, there were clumps being found, sometimes up to 60 on the side of the road, or inside parks. They don’t hear much of that anymore.

“Now we have a program where you give us $6 and we give you a hazardous disposal container, you fill it up with needles, bring it back and we’ll dispose of it.” Regardless of how they’re being used — for insulin, allergy meds, illicit drugs — needles should never be thrown away in the regular trash without being in a specific disposal container.

From what Blevins is hearing, there seems to be a decrease in heroin usage. “My guess is our law enforcement does a really good job of saying if you’re dealing heroin in our county, we’re coming for you. I’m pretty sure those were Derek’s (Robbins) exact words.”

There’s also been a change in community perception about the program. At first, there were quite a few voicing opposition; not so much anymore.

Photo by Bobbie Curd/bobbie.curd@amnews.com

Brent Blevins, public health director, explains what’s on the short form of questions clients of the Boyle County Health Department’s needle exchange program are asked.

“But a lot of that is because the ASAP group here is so strong. Kathy Miles (ASAP coordinator) is such a good leader. We have magistrates, commissioners, sometimes the judge and mayor who participate, and other organizations. It helps educate people,” Blevins said. “And the Shepherd’s House — they have been huge, huge educators in the community.”

Blevins said the faith community has been exceptional, as well.

“They have really picked up on it better than I thought. Many have the Celebrate Recovery programs offered every night … I think it’s helped changed some of the thinking that anyone who does drugs is just wrong and going to hell,” Blevins said. He said now, many realize it’s a societal or community issue as opposed to “a sin.”

Blevins said the 2015 event Hope over Heroin, organized by Pastor Brian Montgomery with Danville Church of God, seemed like it was the turning point. After multiple deaths were reported due to heroin and fentanyl, a synthetic opioid, the event was put together in order to offer those struggling with addiction help and resources. It also brought much needed awareness to the public about addiction, Blevins feels.

But as always, when one drug gets more press — more deaths, more arrests and more education being spread — it makes room in the market for another.

“One guy came in saying ice is back out, big. That’s the newest thing. The ‘ice’ threw me off — I put my pen down and said ‘tell me more.’”

Ice is the purest form of methamphetamine, also called crystal meth, and comes in a white rock. It’s completely different and way more powerful than the homemade meth, which has seen a huge decrease due to the difficulty in getting Sudafed and other ingredients.

Traditionally, meth has been snorted or smoked, but now it’s melted down and used intravenously.

“In two years of the program, that’s the first person who had reported shooting up meth. Up until about five months ago, everyone said heroin,” Blevins said. “If it’s not heroin, it will be on to the next thing, and I think that’s becoming meth.”

Coming up

Check back on Tuesday for more on the drug many say is on the horizon to be the next epidemic — crystal meth. Read more about the highly addictive and toxic substance from local and state officials; a physician’s take on treating meth addicts and its long-term effects on the body; and two former users going through rehabilitation who share their stories.