SAP director at jail open about past, giving chances and why laws should change

Published 6:27 pm Tuesday, April 23, 2019

- Tanith Wilson, the director of SAP at the Boyle County Detention Center, uses her own story of battling drug addiction to help pave the way for others to heal. Photo by Bobbie Curd.

Tanith Wilson says sure — you have to be loving and compassionate in her job, but you have to be tough. Wilson is the director of SAP at the Boyle County Detention Center, which is the substance abuse program administered through a contract with Shepherd’s House.

“For one, drug addicts are the most difficult population that any mental health professional can deal with, so you have to be tough. And, of course, when you have them in this kind of setting, it’s even worse,” Wilson says from her office, just outside the SAP unit at the jail. Here, when helping addicts work through their disease, she says you also have the criminal code to deal with, and the inmate attitude can be hard to get past.

“They’re great though — they’ve come a long way.”

A walk into the SAP unit shows just how far these guys have come. “Attention!” one of the peer leaders yells as we enter. They all stand, until she tells them they can relax. There’s an upbeat vibe, but they are respectful and attentive to her.

SAP clients are all state inmates, determined through an application process at the Department of Corrections level, which has a lengthy waiting list. Lisa Lamb, communications director with the DOC, says there are 2,567 on that list, and they are strategically placed in treatment “towards the end of their sentences so we can immediately connect them to aftercare in the community for continuity of care.”

Wilson and her colleague, Alex Gardner, work with a class of 40 clients who start as freshmen, graduating up to seniors, then some become mentors by the end of the program.

Inmate Joey Price, a client with SAP, stands with Wilson in the hallway outside the unit. “I’ve learned more about my own characteristics and issues. I had a bad attitude when I was first here, and almost got kicked out,” Price said, but following the SAP program has helped him learn to be less aggressive. Photo by Bobbie Curd.

Wilson has been with SAP for over two years, but in the field for 11. First, she was employed by a private, self-pay rehab where she worked her way to director. After getting her degree, she decided she needed more of a challenge and maybe something that fit her own personal past better, where she could lead by example.

“I’m a recovering addict — 12 years sober,” she says, her smile beaming, and she’s gotten a second bachelor’s degree and is currently working on her dual masters in addiction counseling and mental health. But she says “recovering” because it’s a continual process.

Wilson is still involved in AA as a sponsor, and still has a sponsor. She’s learned through the 12-step process that once we stop believing it’s a disease is “when we think we can have a drink on the weekend like normal people, which can lead back to the serious drugs …”

Wilson got an eight-year sentence when she was 19 years old for manufacturing methamphetamine, her drug of choice. She can identify with many of her clients’ life stories; she began using when she was 13 with her parents, starting with pot, going to pills, cocaine then meth.

She says like many of the guys in here, drugs were a natural progression in her life; to not do drugs was abnormal. And it led to serious legal problems, after first being in the state’s custody because she was out of her parents’ ability to control, then on to making and dealing drugs to support her own habit after the state gave up on her and returned her to her mom’s custody when she was 17.

The only difference between the guys in jail and the ones who can afford private rehab, she says, is resources. In her former job, she treated district attorneys, deans of schools, sons and daughters of doctors and lawyers, and doctors and lawyers themselves, all who could afford the $5,000-$8,000 monthly price tag of private treatment. Addiction knows no bounds, she says, but where it takes you in your life has a lot to do with what you’ve got at your disposal.

And like Wilson does, the program encourages clients to tell their own stories and work through them, but not to harp on the glorification of drugs; not even on the war stories. “We are more focused on the solutions,” she says.

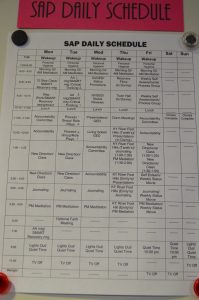

The SAP daily schedule is a tight one for the 40 clients in the program. They have eight hours of programming a day, ranging from accountability and recovery training, to journaling, AA meetings and group therapy. Photo by Bobbie Curd.

She leads psychoeducational classes, teaching clients how substances affect their brains, their path of maturity and reasoning. They have parenting, job skills and communication classes, to prepare them for reentry into society; relapse prevention courses, performing skits on how to deal with being offered drugs; AA classes; group therapy … Their schedules are tight, as seen on the board of Wilson’s office.

The guys are ranked into categories of freshman, sophomore, junior and seniors, and once graduated to juniors, they get incentives, like more phone time or the ability to have coffee in class.

“I believe in accountability — it’s what got me sober,” Wilson says, explaining that could be one of the most successful parts of the program. These guys are all very attentive to one another, giving each other “pull-ups.”

“They pull up on each other, tell each other when they’re doing something good or bad,” and have the ability to write each other tickets they use for learning experiences — or LEs.

“LEs are very recovery oriented — an action LE may be we want you to go around and ask 10 different peers what your biggest character defect is,” Wilson says. She has them use the phrase “Change I must or die I will,” in their writings.

Client Joey Price, 35, is a junior. “It’s good as a drug addict and a person who’s been a criminal for a long time, to learn about your character defects,” he says — when you have 39 other people pointing it out for you, it opens your eyes. Price says he’s learned about communication skills, too, like paying attention to what people say instead of thinking of what his next statement will be, and feels the program has helped make him less aggressive.

“They’re writing about why they need to change, what needs to change, and what are the consequences,” Wilson says. “This is a life-or-death disease — people are dying every day. We want them to look at that, write about it, live it.”

Accountability is held Monday, Wednesday and Friday; Tuesday and Thursday they do a lot of class work, or sometimes watch a documentary on recovery.

The system is broken, and Wilson knows that first hand. She didn’t get clean until she relapsed while on parole, and was forced to turn to the Hope Center in Lexington for treatment or go back to prison.

Multiple boards in Tanith Wilson’s office keep the class roster straight, showing each phase each SAP client has completed. Photo by Bobbie Curd.

“I get frustrated with the myth that forced treatment doesn’t work. ‘If the addict doesn’t want it, don’t bother’ is a bad way to think.” Sometimes a person needs to be forced into it and made to stay there long enough for it to start to work, she says.

“Getting clean was absolutely the hardest thing I ever had to do. Way harder than being in prison — it’s not hard to find drugs in prison, not hard at all. Sometimes it’s even easier in a lot of cases,” Wilson says. She says this whole “lock addicts up” is not the solution; in fact, it’s created more problems, almost enhancing the cycle of addiction.

“We’ve tried it for the last 30 years, and all we’ve done is quadruple the incarceration rate, increase spending to house inmates — $23 million this year spent on inmates in this country? It’s not working.”

Trafficking is a serious offense, but most who sell drugs do so to support their own habit, she says. “But, the way the laws are — when are legislators going to wake up, and say ‘hey, we’ve made a mistake, this isn’t working, let’s back up off it some of this and make a change.’”

And it’s nothing for an addict to buy two grams of something — the amount that designates the trafficking charge — because everything is so cheap these days. “Now, you’re bogging down the system even more, giving these lengthy sentences to people with diseases, instead of offering treatment.”

Wilson says the laws are getting worse instead of better. A few years back, it changed to anyone charged with trafficking heroin must serve 50 percent of their sentence before being able to seek parole, when it was 20 percent before.

“Someone who just left their dealer’s house, gets pulled over and caught and charged with trafficking, then five years in prison, and they’re just an addict. They’re not even selling. It’s just insane,” Wilson says. “If you would treat the disease … And it’s not successful for everyone — I wasn’t successful the first time I tried to get sober either, or the second or the third time. But we don’t give up on people, we keep trying. Look what happened to me.”

Wilson says her worst days on the job are when they hear of a former client’s passing, due to overdosing when they relapsed after getting out. But her best days bring that smile back.

“Probably when you hear from an old client. Some will call and let us know how they’re doing. They may even say they relapsed when they left, but remembered what we taught them and got through it, or that they’ve been great and wanted us to know we had an impact on them,” Wilson says. “That’s my goal. I want to change people’s lives, like mine was changed.”