Danville man invaded Normandy from above — ‘I was lucky’

Published 9:05 pm Wednesday, June 5, 2019

- Paul Chandler, 100, of Danville, was a member of the 82nd Airborne Division 325th Glider Infantry on D-Day in Normandy. (Photo by Robin Hart)

Seventy-five years ago today, Paul Chandler was a 25-year-old American soldier silently riding in a glider over enemy lines in France, as part of the D-Day assault against German forces during World War II.

Chandler is 100 now and lives in Danville. But he still remembers a lot from his time as a member of the 82nd Airborne Division, 325th Glider Infantry, which landed in the Normandy region on June 6, 1944.

“Everybody was scared to death that day,” Chandler said. “Before we left, they gave us chewing gum to chew to keep us from being so nervous.”

On the night of the invasion, the glider infantry flew over the enemy, but Chandler’s unit didn’t land where it was supposed to.

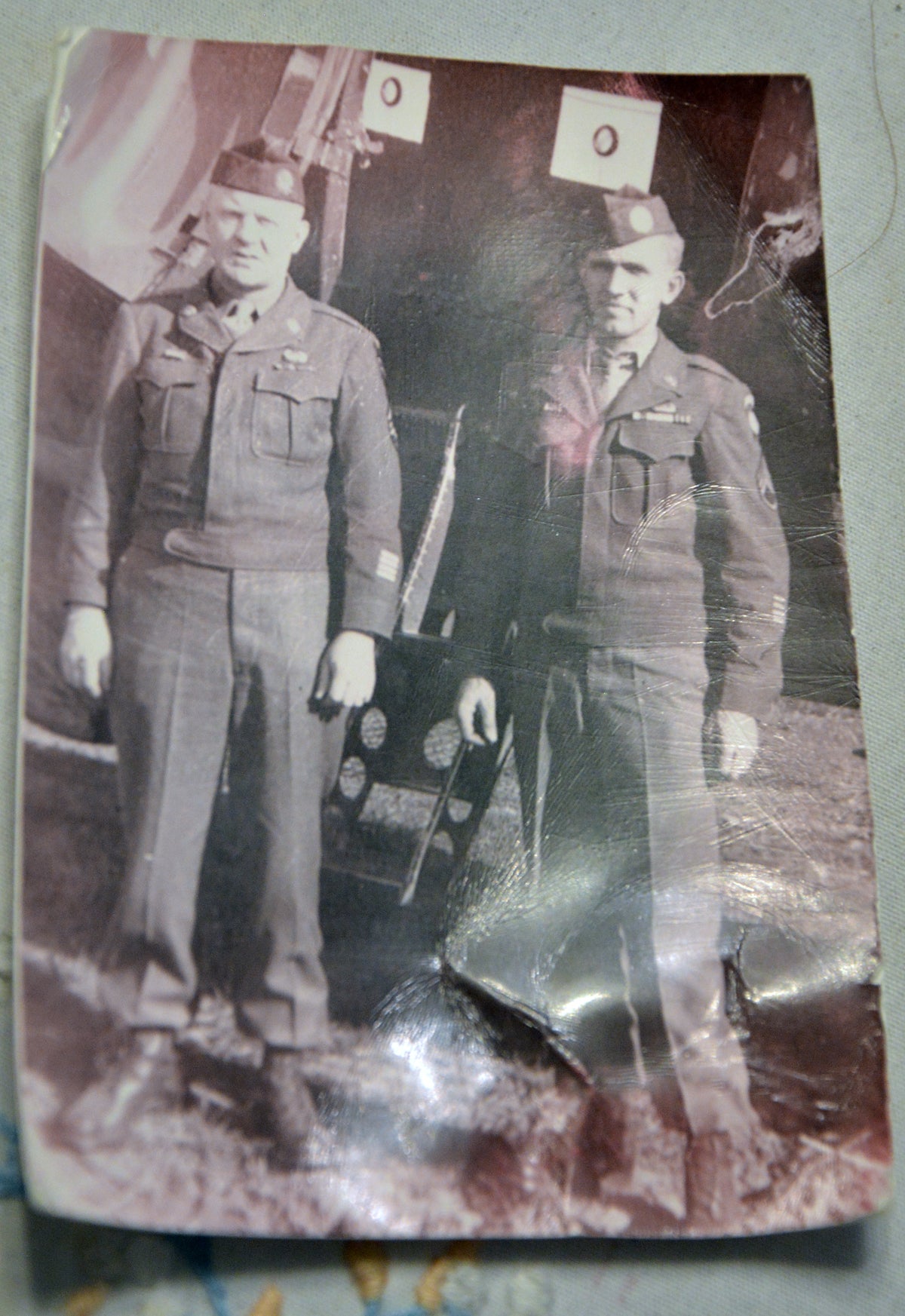

Paul Chandler poses for a photo in his uniform during WWII. His son Jim Chandler said the 82nd Airborne Division of which he was a member, was the only group allowed to wear baggy pants that were stuffed down in their shoes.

“Our glider tore all to pieces when we landed,” he said. “Most gliders tear all to pieces when you hit the ground.”

Chandler said the wheels were attached to a small wood frame, but the rest of the glider was only made from lightweight canvas. “You could stick your finger through the side of it.”

Chandler said there were about five men and a gun in each of the gliders that night.

“When we jumped out of that thing, everybody was trying to find his way. It was dark,” Chandler said slowly in a gravelly voice. After a few seconds to take a breath, he said, “In the night, we got scattered out there. And one time we was laid down in a ditch in water, trying to stay down from rifle fire. It was awful hectic that day.”

Eventually, about 15 of the 25 men found each other and reassembled, Chandler said. “That’s about all we did that day, as far as I can remember.”

The next morning, the men joined another outfit and continued fighting for the next several days, Chandler recalled. “Nobody thought we would have enough ammunition and everything … there to stay on. They thought the Germans would run us off. But so many people got killed there — on our side and their side.”

Chandler started his military career when he was drafted. He was inducted into the Army on Nov. 28, 1941 — just nine days before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. “Roosevelt saw the war was about to happen and he decided to draft all the boys from 18 to 24. … They called my name pretty early.”

One of Chandler’s sons, Jim, said his father’s two brothers also served during WWII, and “they all came home,” he said.

Sitting at his kitchen table next to his sons Jim and Mark, Chandler asked for one of them to bring him a box that contained several medals he had earned while serving for 46 months during the war.

Inside there were also two small pages, which he unfolded — a handwritten note listing the dates and places where he was deployed to. “It’s the history of where I was. I’ll read it. Left New York, April 29th, 1943. Arrived in Casablanca, May 10th, 1943. Left Cassablanca, May 19th and arrived in North Africa, May 23rd. … It was a little old town there in North Africa.”

The first battle that Chandler fought in was before D-Day in Sicily, in September of 1943, he said. From there, he traveled with his regiment to Naples and ended up in Belfast, Ireland on Dec. 9, 1943, before traveling to Lancaster, England.

When he was fighting in North Africa, it was the first Chandler had ever seen a glider. It was also when he was assigned to the glider unit. “A lot of people were afraid of those.”

Chandler said he fought in battles in Africa, Sicily, Italy, England, France, Belgium and Holland. The last time he fought was in the Battle of the Bulge, “when the war ended,” Chandler said. “That was the worst fighting I was ever in. Lots of people got killed.”

“I don’t know how many people got killed on D-Day. Lots of them got killed going in on a boat …. and they had to wade waist deep in water to get to the shore. And a whole lot of them drowned before they could get to shore with all that packing on their back. And a lot of them got killed by rifle fire. But we dropped in behind the lines in the glider outfit. I was lucky.”

Chandler was with the 82nd Airborne Division when it liberated the first town in France — St. Mere-Eglise.

Sometimes Chandler carried a .45 handgun, sometimes a Thompson sub-machine gun or an M1 Carbine.

Paul Chandler holds a faded black and white photo of himself, far left, and three of his buddies during World War II. (Photo by Robin Hart)

“I did my part of shooting, but as far as I know, I didn’t kill anybody. You didn’t know whether you did or not. … There was so much killing going on,” Chandler said.

“I had a lot of nice boys that I got to know, who got killed on D-Day. One of them was from down in LaGrange, some big, red-headed boy. I remember him, he got killed on D-Day.

Chandler said many of the soldiers got used to seeing people get killed. “It didn’t bother you a whole lot. I’ve seen truck loads of bodies stacked up in trucks …. in the Battle of the Bulge. Death didn’t mean a whole lot to anybody,” he said as he stared across the room.

Chandler said his regiment later captured a Jewish concentration camp in Belgium. “We went in there, and it was just — there was dead bodies laying down and some of them were living.” And there were old turnips laying in the dirt half eaten, Chandler recalled. “They was skin and bones. They had been starved to death. And the stink … the odor was awful.”

After all of the battles Chandler had survived, he had earned enough points that he was allowed to go home, his son Jim said. “He didn’t go into Germany.” Soon afterward, his division was appointed to be the honor guard in Berlin, “but he didn’t get to go,” Jim said.

After being discharged in September of 1945, Chandler said he and the other men had to wait for about three months before a ship was able to take them home, because so many were still being used to take troops to the Pacific, where the war wasn’t over yet, Chandler said.

While waiting on a ride home, Chandler said he and several other discharged soldiers were sent to the French Riviera for a couple of weeks. “That’s when I first saw the bikinis. … All the girls were running up and down the beach in their bikinis!”

One of Chandler’s most cherished medals stored in his simple box is the one he received from the French government in 2004, when a delegation presented soldiers who fought in Normandy with the special medal, thanking them for their part in liberating the country.

“All those medals, they don’t mean a whole lot to anybody else, but they do to me.”

- Paul Chandler keeps his Worl War II medals,ribbons and dog tags in a box. Photo by Robin Hart)

- Paul Chandler shows the Normandy medal that he was presented with by a delegation from the French government in 2004. Photo by Robin Hart)

- Paul Chandler shows where on the sleeve his 82nd Airborne, 325th Glider Infantry patch would go. Photo by Robin Hart)

- Members of the 82nd Airborne, 325th Glider Infantry have this glider pin. (Photo by Robin Hart)