Veteran surprises returning soldier with unique welcome

Published 8:32 pm Thursday, August 1, 2019

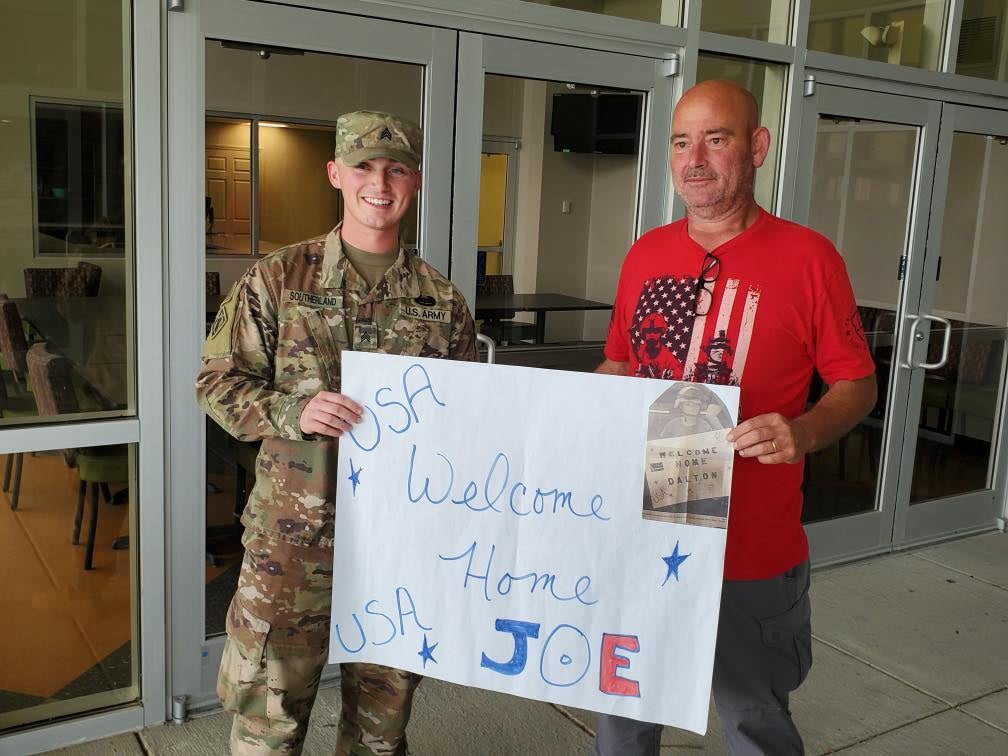

- Sgt. Joe Southerland stands with veteran Dalton Miller, who made a special sign for his homecoming on Tuesday at Fort Knox. (Photo contributed)

Army Sgt. Joe Southerland, 23, returned home Tuesday after nine months in Afghanistan. When he rolled into Fort Knox, he found family and friends waiting for him, cheering and holding signs. One sign in particular really stood out to him.

Joe Southerland, as an 8-year-old, awaits Dalton Miller’s arrival back from Iraq 16 years ago at the National Guard Armory in Danville. (Photo contributed)

“I knew he was going to be there, but I didn’t know he was going to make a sign,” Southerland said Wednesday, about longtime Stanford neighbor and family friend Dalton Miller. “I remembered it as soon as I saw the picture on the poster.”

Miller, 50, had returned home from Iraq 16 years ago. When he arrived at the National Guard Armory in Danville, a then 8-year-old Southerland was waiting for him with a homemade sign, caught in the moment by former Advocate-Messenger photographer Clay Jackson.

“When Joe joined the military and deployed to Afghanistan, I told my wife I was going to make the sign and put that picture on it,” Miller said, who had kept the clipping of Southerland. “I had no idea it was 16 years, almost to the day. Joe was there for me, with that poster, and I wanted to do the same for him. I wanted to put his poster on my poster.”

“I remember having that kevlar hat — Dad always told me it was for my own protection,” Southerland said and laughed.

Dad, Mike Southerland said his son was always into “anything military.” He said the kevlar helmet was given to them by Andy Ferguson, a former police academy instructor, now a Lincoln County Sheriff’s deputy.

“It was too small for any of the cadets, so he gave it to Joe. I went online and got him a desert camo cover … and gave him my tanker goggles.” Mike Southerland served from ‘89-91 in the Army.

He said when Miller was sent to Iraq 16 years ago, “Joe was worried to death about him. And he wore that helmet everywhere — everywhere.”

Fast-forward 16 years, Mike Southerland said, “and Joe returns. We got in contact with Dalton, and he said, ‘Joe was there for me, I’m going to be there for him.’ It’s just a feel-good thing, and good for people to know about. Especially today, with all the BS going on.”

Joe Southerland was deployed for nine months with the 19th Engineer Battalion’s 42nd Clearance Company, with around 140 soldiers last fall. His platoon worked in Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second largest city, clearing the roadways of IEDs (improvised explosive devices) for the Army, NATO and Romanian units, all part of Operation Freedom’s Sentinel, spanning throughout the southern part of the country.

Joe Southerland said the area is referred to as the “Taliban’s summer home. They come over there from the Helmand River to Kandihar, so we did find a few IEDs. The fourth platoon found a bunch of IEDs out in Dwyer,” he said, referring to the area near Camp Dwyer — a Marine base located in the river valley area.

He was the one with his platoon who talked to the locals through his “terp.” “I had an Afghani interpreter who rode with me. It was a little tense with the locals.”

According to news reports, two U.S. soldiers were killed in Kandahar Monday by an Afghani soldier. Earlier that same day, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had said President Trump directed him to decrease the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan — by the 2020 election.

Dalton Miller is pictured 16 years ago in 2003, when he was headed to Iraq with the National Guard. (Photo contributed)

“Road clearance is the most dangerous job to do in Afghanistan,” Joe Southerland said. “We take a lot of pride that we did it. No one got seriously injured with us, and I’m glad we got all the guys back home.”

The last nine months have been a lot of work, he said. “We were pretty much out of the wire (off of the base) pretty much every day. We were very active, between the QRFs (quick reaction force missions) and doing the bloodhound missions (road-clearing). Whenever we get attached to infantry, we’d clear in front of them, they’re right behind us.”

But he missed a lot while he was gone, too. His granddad, Darrell Southerland, passed away in late May, who was also a veteran. “I saw my granddad’s grave for the first time at Camp Nelson yesterday. I didn’t get to come home for the funeral, but I did get to watch it over FaceTime,” he said. Serving his country in the military is something he’s wanted to do since he was small, and he knew there would be sacrifices.

“They put their life on hold for America, and they all know that when you take that oath, you’re all taking the same oath …” Miller said, regardless of what branch you’re serving in. “Regardless of what you’re asked to do, you know that day you’re sworn in — that’s a possibility. Putting your life on hold to serve your country is one of the most noble things you can do.”

Miller joined the Army when he was 17, with his mother’s permission. Later, he went into the National Guard, and was in the Gulf War and Iraq War. The “welcome home” greetings for soldiers are very important to him.

Sgt. Joe Southerland, third from left, stands with the rest of his unit in Kandahar, Afghanistan on the Fourth of July. (Photo contributed)

“I think America learned its lesson with Vietnam. When you don’t support the soldiers when they come home, it creates more problems in the long-run,” Miller said. “For lack of a better way to say it — we had to screw up a lot of people to realize what kind of mistake was made. I vowed to never let that happen again, personally, with any soldier coming home …”

MIller said every soldier deals with what they’ve been through differently. “That’s where a lot of the mental health issues comes from, the overall stress it can put on a family or individual. I’ve lived it twice, and hopefully I can help.”

Joe Southerland enlisted when he was 18. “It’s what I’ve wanted to do all my life. I”ve checked all the boxes … so now I’m figuring out my future. I’ll cherish everything, but it’s to the point where I want to be home now.”

Miller said most people can’t understand the bond that develops among soldiers. “You can’t explain it. I call him ‘Joe,’ because he’s like my own. Sgt. Southerland I guess is what I should call him now. But Tuesday, I didn’t call him Joe — I called him brother. He’s my brother, now.”