Coming together: In the 1960s, integration tore many communities apart. In Danville Schools, ‘it wasn’t an issue for us.’

Published 7:51 pm Thursday, September 19, 2019

- Staff members of The Log, Danville's student newspaper, pose for their yearbook photo. (DHS 1965 Yearbook)

It’s been 55 years since the brand new Danville High School building opened its doors and was fully integrated with white students from the old high school on West Walnut Street and black students from Bate High School on Stanford Avenue. This also made the class of 1965 the first to graduate from the brand new DHS building.

Since this is DHS homecoming weekend, it seems like a good time to recall a bit of the school’s history.

Two local former students who attended DHS that first year recall similar experiences, yet there were a few differences. Also, previously recorded interviews by David Davis of Danville and Bate teachers who were working at that time show they held different opinions on how the integration process went.

Joe Morely, class of 1965 and owner of Morely’s Wheel Service in Danville said he didn’t remember integration of the schools being much of a polarizing issue. He said unlike in larger cities and in towns further south, integration and racial conflicts weren’t part of the Danville culture. Sure, there were a few whites and blacks who didn’t want to attend the same school, but, “We knew each other. We just grew up together. … We were all just buds.”

Morely said, “Maybe it was just me, because I was very much of an extrovert. My buddies and I, we just didn’t think a thing about it.”

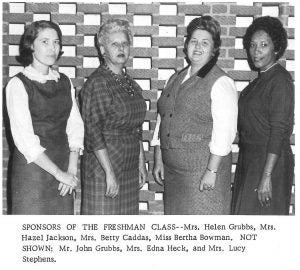

Sponsors of the freshman class in Danville High School’s first year were, from left, Helen Grubbs,Hazel Jackson, Betty Caddas and Bertha Bowman; and not pictured, John Grubbs, Edna Heck and Lucy Stephens. (DHS 1965 yearbook)

Morely pulled out his 1965 yearbook and flipped through the pages.

Even the foreword written on the first page doesn’t mention anything about it being the first year of integration. It stated, “This school year 1964-65 marks another era in Danville High School’s program of providing maximum education for the students of our city. The new high school building stands as a tribute to the citizens of Danville whose efforts and interest have brought an aspiration into reality.”

Looking among the portraits of teenage boys wearing sport coats and narrow ties, and girls whose bare shoulders were framed by V-necked drapes, Morely began pointing out his black and white friends. He talked about people he was still friends with and those who have died. Again he said, “It wasn’t an issue for us. We didn’t notice any difference.”

The difference he did notice was the new building. Morely had attended DHS for three years at the old building on East Walnut Street, which was nicknamed “the Greenhouse.”

The new building “was clean and new and solid, compared to the old rickety wooden floors” in the old school. However, Morely said he didn’t recall anyone making a big deal out of the opening of the school either.

Morely stated again how he felt integration occurred at DHS. “I think I can say that there wasn’t controversy as if I were white or black. I think we all felt the same way.”

Bobby Trumbo, a member of the DHS class of 1967 and retired teacher from the same school, agreed that integration was easily accepted by the students in high school.

Trumbo attended the all African-American Bate School through ninth grade, before the school board enacted integration. They called DHS “the white school,” he said.

At Bate, “We had some good teachers that prepared us … not only to transition from Bate to Danville High School, but they prepared us for life,” Trumbo said.

“I grew up with white friends and we weren’t even integrated. But we would always come together and play at Jennie Rogers after school — black and whites. We’d play basketball and baseball. We’d just do different things together. In the wintertime, Jennie Rogers’ hill was our sleigh riding place,” Trumbo said with a laugh.

In 1956, he said a few high school students were asked to volunteer to go to DHS as a trial — mostly the athletes, he recalled.

Then in 1964, integration was enforced.

“To some of us, it wasn’t a big thing; to others it was just devastating. I don’t know why it was so devastating to some, but it wasn’t for me.”

Some African-American students ended up dropping out of school, he said.

Some of the teachers were prejudiced, he said. “I don’t think they had enough time to accept integration.” Most of the teachers, however, had every student’s best interest at heart.

In an English class, Trumbo said the teacher called him to come and sit in the front of the room. He felt he was being punished, and he asked her why.

The white teacher answered, “You do not need to be back there. … I looked at your records up and you are a good student and you’re going to remain a good student, and you’re not going to get in any trouble with those that are probably wanting to start trouble.”

Trumbo said the teacher told him that while looking straight into his eyes. “She looked me squarely in the face and said, ‘Do you hear me?'”

Trumbo said at that moment he understood she expected him to be successful in school. “I never will forget it — Joyce Gordon,” Trumbo said was the teacher.

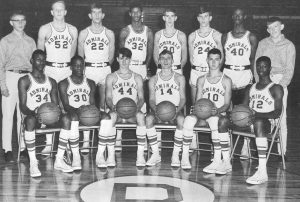

The DHS 1965 basketball team poses for their yearbook photo. (DHS 1965 Yearbook)

He recalled his first impression of the DHS building. “Coming up Lexington Avenue to that big beautiful new building,” he said as his voice trailed off. “That building was state of the art, first-class in the state of Kentucky, all around. We just could not believe that there would be a building with a school having so many opportunities for all the students.”

But some of the residents around the new building didn’t want it constructed on Lexington Avenue, “Millionaire’s Row,” Trumbo said. It was some of the adults who had a hard time dealing with integration, not the kids, he said. “They were very against black kids walking on Lexington Avenue near their homes.”

“The kids, if they had a class with a black teacher, they just had a class with a black teacher. It wasn’t the kids. It was the adults that really kept the fires ignited — segregation fires,” he said.

As a student during the first few years of integration, “Everybody was the same. … Really and truthfully the only time you saw color was when you got mad.”

In a 1980 recording of a retired African-American teacher who taught at both Bate and DHS, she said, “People have a way of fearing the unknown. They didn’t know how they would be accepted or how they would be treated, so there were fears, I suppose. And yet, there were those brave souls who welcomed it.”

A retired white teacher was recorded as saying of the process of integration, “it seems there was no major problems that I was aware of. I feel that Danville has a situation that is rather unique to Danville and I contribute this to the smooth transition there.”

Trumbo said, “Danville is unique because we weathered the storm together during integration. … When we integrated, everybody thought it was going to be this great big problem. But it was no big problem. … We were very unique,” Trumbo said. “We didn’t have the problems that other schools our size had. Danville is a very unique place to live.”