One Day: Repairing motorcycles never gets old for Casey man

Published 8:01 pm Tuesday, September 24, 2019

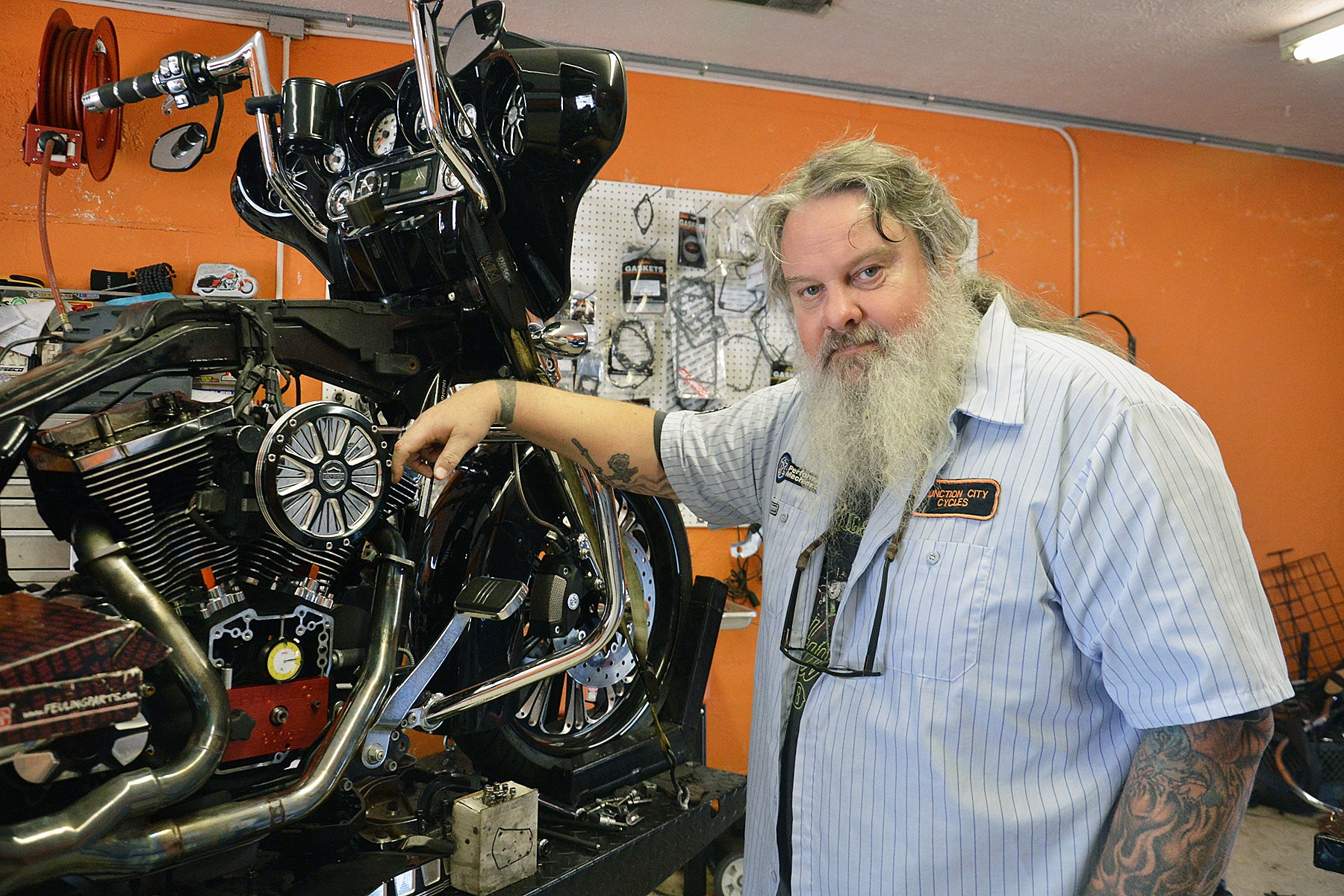

- Randy "Shotgun" McQueary has worked on motorcycles nearly all of his life. He owns and operates Junction City Cycles. (Photo by Robin Hart)

When Randy “Shotgun” McQueary, graduated from Casey County High School in 1987, “I didn’t want to be a gate builder or work in the saw mills. I just wanted something a little different.” So as a young man, he moved to Georgia and ended up repairing motorcycles, a skill he began developing as a teenager while working on his own bike.

McQueary, left and his brother, Chad “Dog” Wagoner prepare to take a bike’s wheel off to replace the tire. (Photo by Robin Hart)

He repaired motorcycles for years without having formal training. “I wrenched for other people,” McQueary said standing inside his own motorcycle repair and accessory business, Junction City Cycles. “It’s a family operation,” he said as his brother, Chad Wagoner — everybody calls him “Dog” — changed a bike tire.

His wife, Renee, has a sideline business in the back of the shop where she sews and repairs leather items, and his daughters work behind the counter sometimes when they’re not attending CCHS or Berea College. “They don’t want to get their hands dirty,” McQueary said with a chuckle. They earn 5% from the sale of accessories for their college fund, he added.

Seven years ago when he opened Junction City Cycles, McQueary was crammed into one bay area of the commercial garage he owned, and rented out the rest of the space to two other small businesses. His reputation of repairing motorcycles, especially Harleys, grew and when one of his tenants closed, he expanded to sell accessories. When the second tenant moved out, McQueary added leather motorcycle apparel. “It’s always a work in progress. It’s tripled in business size in about seven years,” he said.

“The Lord has blessed me in many ways.”

On a typical day, McQueary tries to get into the shop unnoticed so he can work on the books, something he had to learn, and have extra time to work on the bikes. He said during the day, the phone is always ringing, people stop by for minor repairs and new tires, the UPS delivery person drops off boxes and needs a signature, part orders need to be made, and friends are always welcome to have a cup of coffee and talk about upcoming rides. They can even watch McQueary and his brother work on the bikes. “There’s always something going on.”“I like all Harley’s. I like the old classics, the old pan heads and things,” he said.

“This is my passion. It never gets old. When you take one that’s not running and it’s got serious issues and you rebuild it and fix it and you start it up, that sense of exhilaration just goes from head to toe.”

“We get old crusties in a lot of the time. They drag them out of the woodwork. Sometimes they come in boxes,” he said. “We’re not just selling parts, we actually work on them.”

“Shotgun” McQueary’s leg cast hangs on the wall of his motorcycle repair business in Junction City. (Photo by Robin Hart)

“I’ve been working on bikes for 30 years. There’s very few things, at least on a Harley, that I haven’t seen.”

One trend he’s noticed but doesn’t like is the use of tiny, plastic parts, when the older models used “heavy duty” metal parts and were less expensive. “They break all the time. … I don’t see how that’s better.”

McQueary said he’s always been around cycles. His grandfather, who was also called “Shotgun” (McQueary was first called “Little Shotgun) rode a Harley in World War II; his dad was a Vietnam veteran and his mother was in the Navy and they both rode motorcycles. “I didn’t have much choice. We all rode,” McQueary said.

When he was 22 and living in Georgia, McQueary bought his first used Harley Davidson. “I didn’t even make it home on it. I had to push it home. And so the learning process begun early,” he said. He couldn’t leave the bike on the side of the road and pick it up later or it would be gone.

“They didn’t have cell phones back then. So you either worked on it or you pushed it.”

Years later, “A 22-year-old kid on a cell phone” ran into McQueary while he was riding his Harley and he ended up spending a year in a hospital bed, endured several surgeries and got around in a wheelchair and walker, he said.

“I thought, Lord, what am I going to do now?”

He realized he could still work on motorcycles with a little help loading them onto the lift tables. “I got pretty good with my walker getting between the tool box and the table.”

Then in 2005, “I went back to school in a wheelchair.” He earned a two-year degree in motorcycle technology and became a credentialed motorcycle repairman “to sign off on warranty work” for independent dealerships.

The accident didn’t keep McQueary from riding but he warned, “The people out there ain’t watching for you. The day that you’re not scared is the day that you will get hurt on a bike.”

Having a motorcycle repair business prevents him from riding as much as he’d like to. “It’s not really a good profession to be in if you like getting out and riding. You don’t get to ride as much because you’re in here all the time.”

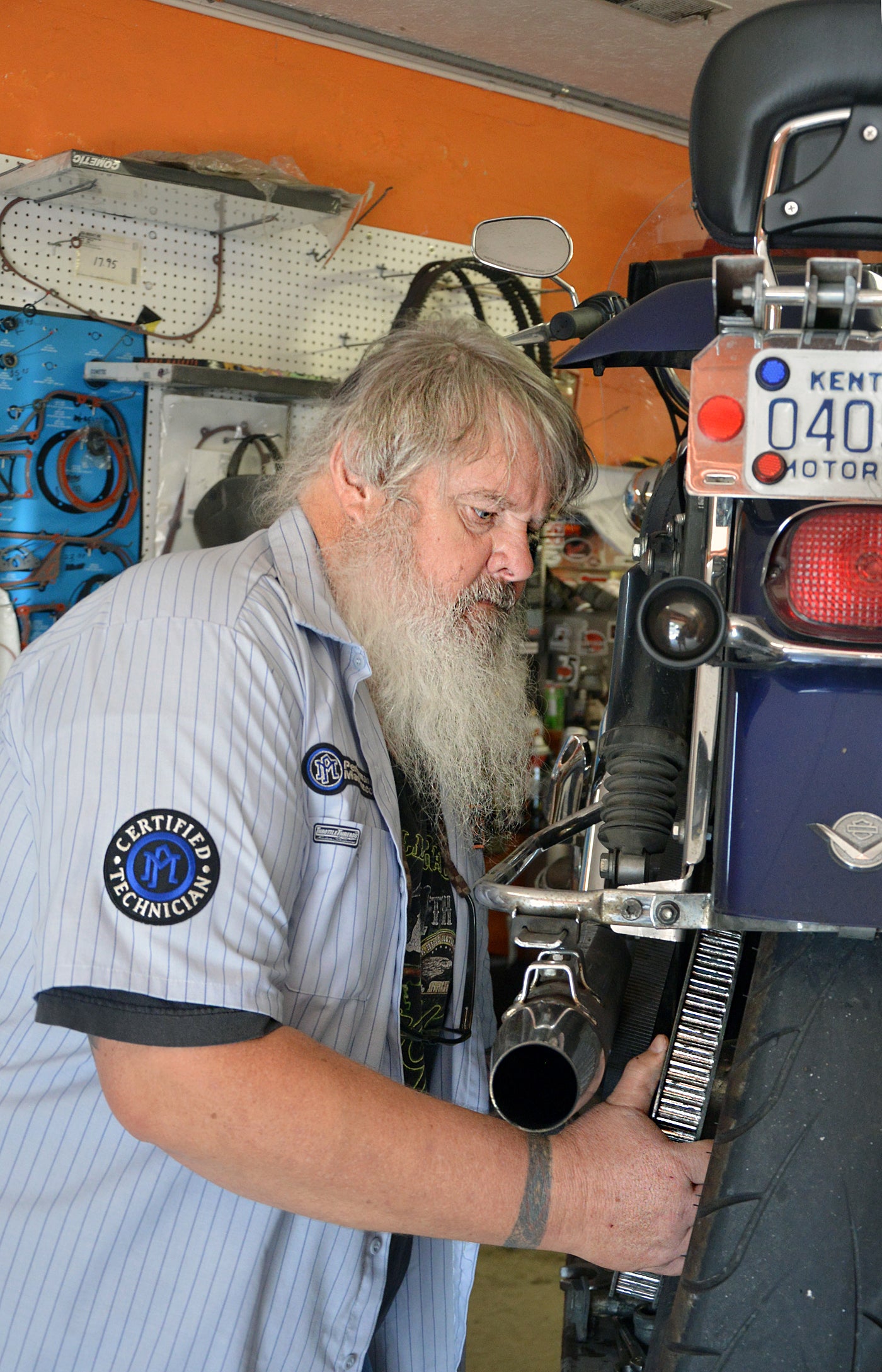

- Randy “Shotgun” McQueary repairs all makes and models of motorcycles at his business in Junction City. (Photo by Robin Hart)

- “Shotgun” McQueary takes a wheel off of a cycle he’s replacing a tire on. (Photo by Robin Hart)

- McQueary replaces a helmet on a rack at his business in Junction City. (Photo by Robin Hart)

- “Shotgun” McQueary talks about a particular helmet’s weight with customer Stan Phillips. (Photo by Robin Hart)

- Randy “Shotgun” McQueary searches for a particular part number in one of the many catalogs he keeps on his desk. (Photo by Robin Hart)

- McQueary gets ready to push Charles Lay’s motorcycle into the shop and onto the lift table to replace the tires. (Photo by Robin Hart)