Brooks was first U.S. Armored Forces casualty in WWII

Published 6:29 pm Friday, December 13, 2019

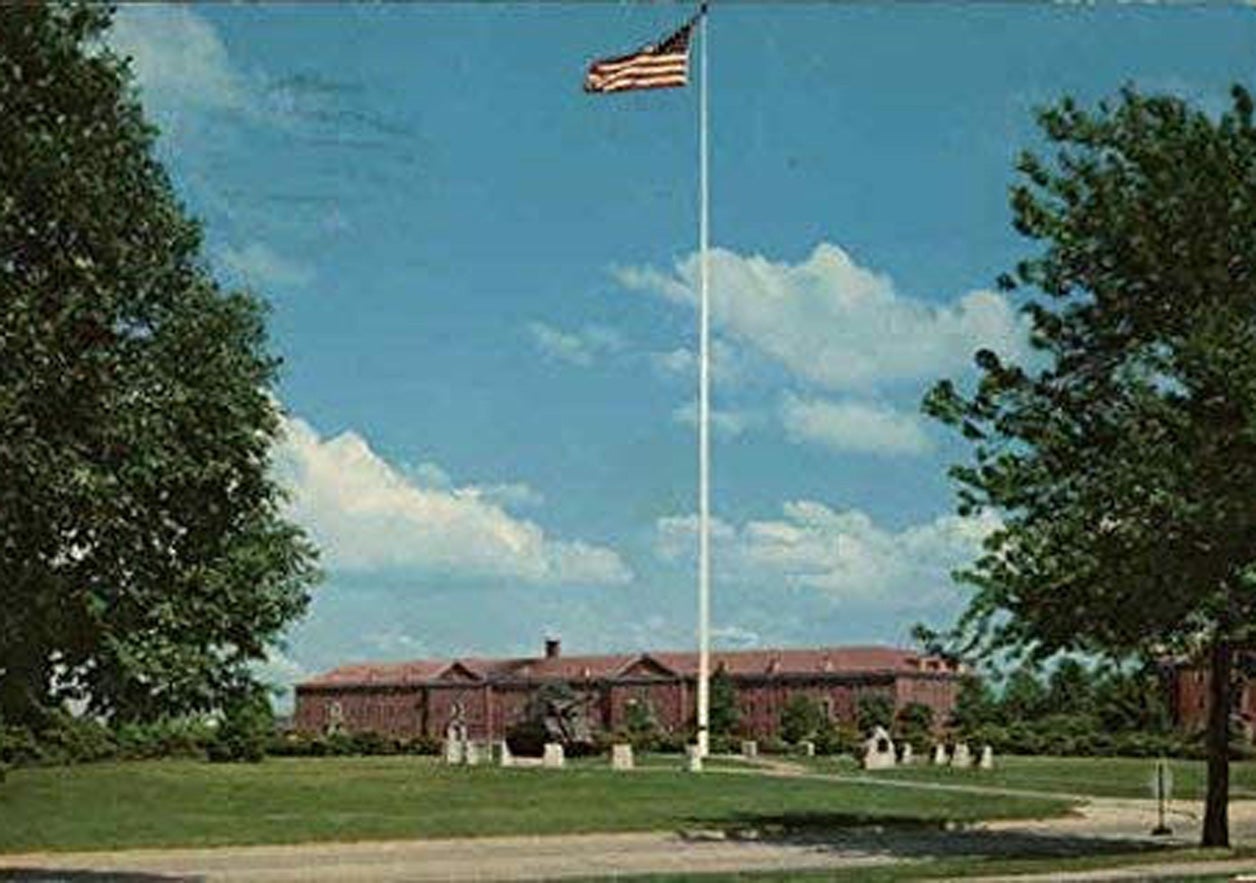

- Brooks Field Main Parade Ground, Armor Center in Fort Knox, was rededicated in the May 2012 Memorial Day ceremony to preserve Private Robert Brooks’ legacy.

(Editor’s note: Information in this article was researched by Andy Bryant, a Danville native, who says he is honored to share Brooks’ military life from information in the Bataan Project.)

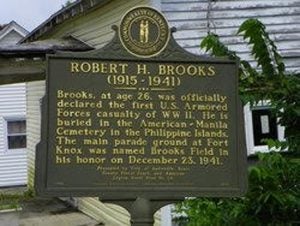

Kentucky native Robert H. Brooks was the first U.S. Armored Forces casualty in World War II and his legacy will be remembered by markers at Fort Knox and his hometown of Sadieville.

Private Robert H. Brooks

Private Brooks was 26 years old when he lost his life on Dec. 8, 1941, in Angeles, Pampanga Province, Central Luzon, Philippines, during an attack by the Japanese on Clark Airfield in the Philippines.

The main parade ground in Fort Knox was named after him on Dec. 23, 1941. Shortly before the dedication of the parade ground, it was discovered he was an African-American who had been assigned to an all-white Army unit. The commanding general at the base stated Brooks’ color was insignificant.

A new memorial marker was placed at Brooks Field in 2011. The original marker is on display at the Patton Museum in Fort Knox which gives information about the day Brooks lost his life in the Philippine Islands.

During the May 2012 Memorial Day ceremony, Brooks Field was rededicated to preserve Brooks’ legacy. A Kentucky Historical Society marker also stands in downtown Sadieville as a permanent reminder of Brooks’ life.

Brooks was born Oct. 8, 1915, in Sadieville and entered the “all white” National Guard unit, known as the “Harrodsburg Tankers”, before World War II began.

Drafted in 1940

A native of Scott County, Brooks was drafted in 1940 into the Army while living in Hamilton, Ohio, and sent to Fort Knox for basic training where he qualified as a half-track and a tank driver.

He attended track vehicle maintenance school at Fort Knox and was assigned to the maintenance section.

He drove the half-track of Sgt. Morgan French, who was in charge of maintenance. French, who was the last surviving member of the Harrodsburg Tankers, died Feb. 28, 2012, at age 92, in Plano, Texas.

Brooks was assigned to D Company, 192nd Tank Battalion a Kentucky National Guard unit which had been federalized. He requested to be in D Company because it only had 66 men.

He was 26 years old when he enlisted in the National Guard on March 15, 1941, in Fort Thomas. He listed his occupation as a sales clerk, and was single.

After basic training, the unit went on maneuvers in Camp Polk, Louisiana, and learned their next assignment was overseas.

The soldiers went to San Francisco, California, and arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii, for a two-day layover and headed for Guam and Manila Bay.

The morning of Dec. 1, 1941, the tank battalions were ordered to Clark Field in the Philippines to guard against Japanese paratroopers.

Seven days later, they learned of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

American planes landed on Clark Field to refuel and soldiers had lunch the day Brooks was killed.

At 12:45 p.m., most of Company D soldiers had gone to lunch except for one left behind with each tank and half-track. Brooks was with two mechanics from maintenance when the first bombs began to fall.

Other members of the unit believed Brooks began running to his half-track and the .50 caliber machine gun mounted on it in an attempt to begin shooting.

As Brooks ran, a bomb, which was a dud, because it landed 20-feet from the tank, hit and killed him instantly.

He was rushed to a hospital where records show him as a white/Mexican.

When the news of Brooks’ death reached Fort Knox, Commanding General Jacob Devers ordered the main parade ground at the base from that day on be named after Brooks.

Dever’s aide contacted a banker in Sadieville and asked him to contact Brooks’ parents, Roy L. and Nell Brooks, and invite them to the dedication ceremony.

A Kentucky Historical Society marker also stands in downtown Sadieville as a permanent reminder of Brooks’ life.

When the aide asked about the parents, the banker, W.T. Warring said they “are tenant farmers, ordinary black people; maybe you could contact and see if they could come.”

This was during the time when the U.S. military was segregated. Blacks served in all-black units and the whites in all-while units.

When the aide reported back to Devers about the parents being black, the general said, “It did not matter whether or not Robert was black, what mattered was that he had given his life for his country.”

Devers wrote a letter to the Brooks couple expressing his sympathy. “Robert was the first battle casualty of the Armored Force, and because of this, and because of his excellent record, I have directed that the main parade ground at Fort Knox be named Brooks Field in honor of your son.”

The dedication was 11 a.m. Dec. 23, 1941.

Brooks Field Main Parade Ground, Armor Center in Fort Knox, was rededicated in the May 2012 Memorial Day ceremony to preserve Private Robert Brooks’ legacy.

In his speech during the ceremony, Devers said, “In death there is no grade or rank. And in this greatest democracy the world has ever known, neither riches or poverty, neither creed or race, draws line of demarcation in this hour of national crisis.”

After the war ended, Brooks’ remains were moved to the American Military Cemetery outside of Manila, where he still lies with the other members of his battalion.

He was posthumously promoted to private first class.