Retired police officer providing big boost to Boyle’s syringe exchange program

Published 8:46 pm Wednesday, March 25, 2020

- Merl Baldwin says he wishes his position wasn't even needed with the local syringe program. "But after doing this, I see how important it is," he said.

The Boyle County Health Department has found a trailblazing way to increase those who participate in its syringe exchange program. A former police chief is now heading up its operation, and Public Health Director Brent Blevins says he’s glad he went with his gut.

Merl Baldwin retired in May after 27 years in police work, most recently as chief of police in Junction City. Actually employed by the University of Kentucky, Baldwin has been the health education coordinator since September.

“I work for the syringe program, in harm reduction — some big fancy term for just the dude who takes care of stuff,” he said.

He landed the job after Blevins called him and told him they had a four-year grant position opening up.

Blevins had worked with Baldwin for some time, specifically remembering calling him one day when he was chief and asking if they could bring the mobile unit to his community. He says Baldwin met them on the side of the road and helped them in any way he could.

But, Blevins admits — he didn’t make the call without some hesitation. “The only piece of me that was a little nervous … We built this thing for two and a half years and people finally trusted us; (now) here, we’re bringing former law enforcement in. It probably took a couple of days before we figured out — hey, this is a good deal.”

Baldwin works with someone each and every day who he’s previously dealt with legally. “I’ve probably worked with hundreds of clients who I’ve arrested. And they come in, ask about my family — that’s just the way it is.”

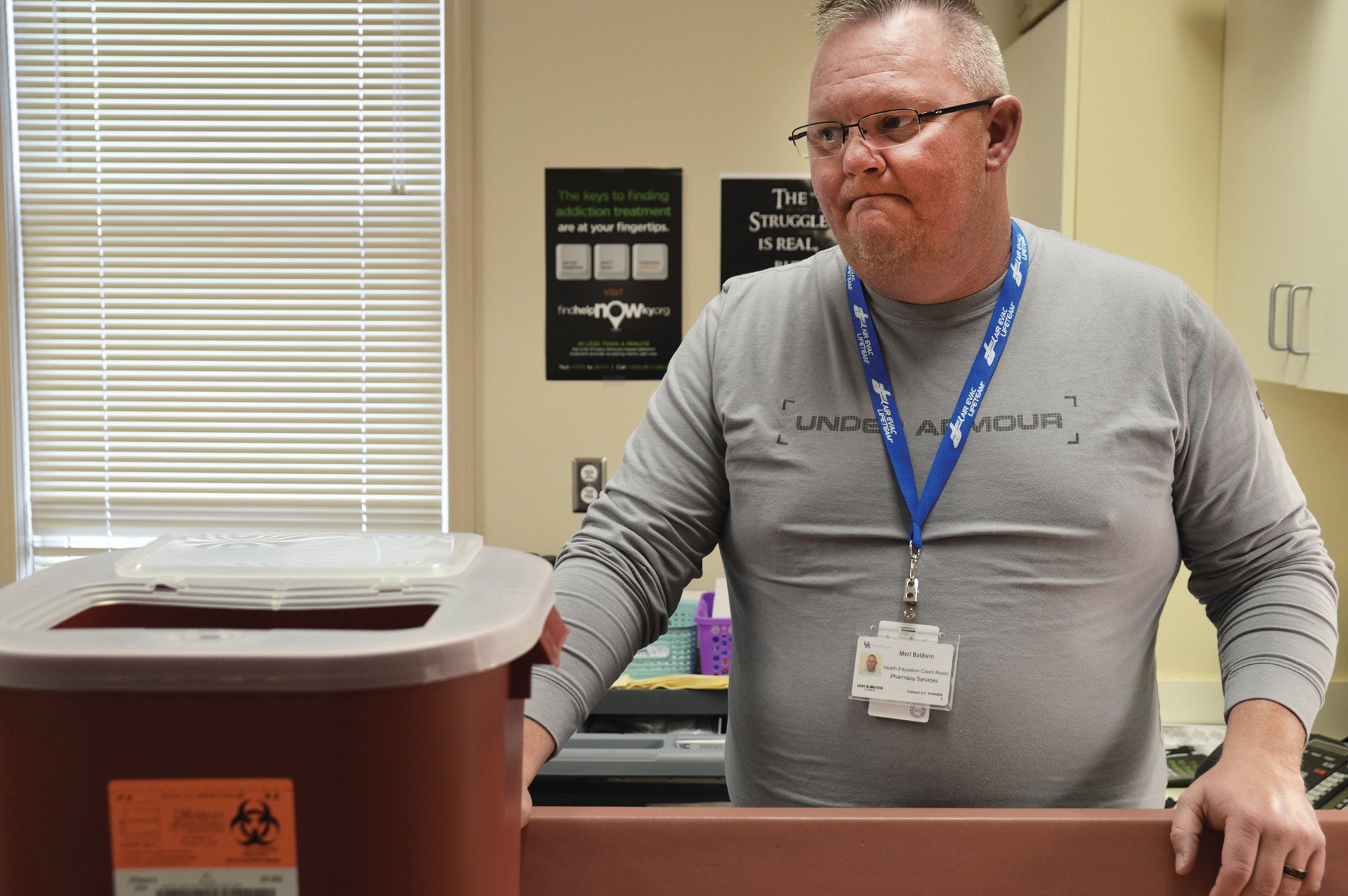

Merl Baldwin goes through all the supplies that are offered to intravenous drug users in the syringe program. They get safe containers, such as the one Baldwin is holding, to safely dispose of dirty syringes, which protects against anyone else getting pricked.

He says it “almost goes against the way UK has trained me.” His counterparts in Lexington tell him no, none of their clients know anything about them.

“I’m like, well, we live in a little bitty community, and everybody knows everybody. I’m like they can drive right by my house, they know where I live.” And he’s fine with that, and those participating in the program must be, too.

The numbers for the syringe program show use has skyrocketed since Baldwin came on board, Blevins says.

For the last quarter of 2019, there were 258 program visits, which resulted in 7,410 clean syringes distributed and 4,324 dirty syringes returned. There are 937 total clients enrolled in the program currently.

Sterlizing pads and antiseptic ointment are just some of the supplies given to addicts by the local syringe program.

Over the programs first two full years, there were 810 enrolled clients and 23,660 syringes distributed — an average of less than 3,000 distributed every quarter, which is less than half of what the program distributed with Baldwin.

Baldwin has also become a consultant of sorts on the grant, as well, offering insightful law enforcement expertise for the program to be able to communicate clearly with other agencies — another priceless benefit of having him, Blevins says.

“I was just talking to a law enforcement guy earlier this morning. He said ‘I’ll just tell you, up until Merl came and talked to me, I was not for this program — thought it was bad.’ Once Merl did it — they trust him. He said, ‘I get it now … We get it now, and Merl is able to talk our language and we understand it.’”

Although hesitant at first about the move, Blevins said he just trusted his gut. “And it turned out to be one of the most awesome things we’ve done. The numbers have gone up. The numbers took off.”

Blevins calls it “a really fascinating study of human dynamics on how this has worked — taken two totally separate worlds that shouldn’t mesh, and he’s figured out how to mesh them.”

Baldwin explained the program is through an organization called KIRP, which is the Kentucky Reinvestment Program, established through the Cabinet for Health and Family Services’ Department for Public Health. Its aim is to improve health care delivery through disease education, prevention, treatment and professional services, such as people living with HIV, through collaborations with the Ryan White HIV/AIDS funded programs, a national foundation for HIV education.

Baldwin explained the program is through an organization called KIRP, which is the Kentucky Reinvestment Program, established through the Cabinet for Health and Family Services’ Department for Public Health. Its aim is to improve health care delivery through disease education, prevention, treatment and professional services, such as people living with HIV, through collaborations with the Ryan White HIV/AIDS funded programs, a national foundation for HIV education.

Baldwin said he is one of two in the state KIRP has hired to do this who are retired law enforcement; his counterpart is in Jessamine County.

“Officers are either tagged as being a hardass or being somebody that’s too soft on crime. I rode somewhere in between that, something anyone concerned with public safety has to deal with … Even people I had to fight with, I had a good rapport,” Baldwin said. He said every single person who came up to speak to him after the fact of him arresting them “understood exactly what I had to do. I based my whole career on that.”

And Blevins says that shows in how he’s received by program participants. “I think because of the way he treated people on that job, they felt like they had human dignity and they trust him. And they still trust him, now, doing this,” Blevins said.

When Baldwin was a police officer, he said he really “didn’t agree with the program from the beginning. I had the mindset, they’re out here using drugs and it’s their stupidity, why should public health give them stuff to help them get high?”

But now, he sees the bigger picture, he says, on viewing addiction as a disease, not a choice.

“And money for this comes from the project … no taxpayers money goes into this, it’s all private funds. That was important to me,” Baldwin said.

And the local health department is making a name for itself with Baldwin in the program. “My direct supervisors with UK were elated with Brent. They tell me this every time I go to a meeting or training, that Brent is a genius because of how he had the forethought to do this.”

Baldwin also attributes his hitting the ground running to longtime nurse Vicki Vernon, who trained him.

“This is the best job I’ve ever had in my life, because now, I can see — I can finally see, after six months, I can see this is not only a good thing but a necessary thing. Every person I’ve come into contact with … I talk one-on-one with them, offer HIV and Hep C testing if they want it. I counsel them, and every person I’ve talked to and asked, ‘Do you want to use these drugs?’ I’ve yet to have anybody say yes. Every one of them wants to quit.”

Baldwin says his eyes are now open to the fact addiction chemically changes a human brain.

“I’ve never lost the part of me that will always be a police offer. But the part of me that is a caring human being has taken over me. Now I can see where this is a needed thing. I’m helping these folks regain their self-confidence, their self-worth.”

He’s also seeing first-hand how “these folks are looked at as second- or third-class citizens. They’re not. It could be my child, your sister …”

Baldwin says he’s lucky, as is the rest of the community, to have many caring groups locally who advocate for addiction awareness. “Like Kathy Miles (ASAP coordinator), meetings with her and Brent, and it’s this group of people who are the most caring people I’ve ever been around in my life. They’ve helped educate me and I’ve really changed my mind on where we need to be in society. What Brent has done to allow us to go mobile with our program, we’re one of five counties that’s mobile.” The mobile unit goes out into the community every Thursday, with locations posted on social media.

Baldwin says Appalachia and Central Kentucky “has some of the highest rates of HIV being transmitted through drug use. That’s part of the reason we’ve got the funding and resources we do.” He predicts that “lots of good things” will be launched throughout the state because of the program over the next five to 10 years.

“Of course, right now everybody’s in COVID-19 mode. Part of our job is anything that’s transmitted, to try and take care of that. We work very very closely (with the rest of the health department.) If Brent needs me to do anything else I will, as long as the clients with the exchange program are taken care of.”

SO YOU KNOW

Walk-in Syringe Exchange Program clients need to use the door to the left of the ramp in front of Boyle County Health Department to access the exchange. This is temporary as an effort to combat the spread of the COVID-19 virus.