Sheriff says claims of targeting African American community are false

Published 9:05 pm Thursday, September 17, 2020

Boyle County Sheriff Derek Robbins says his agency is used to public criticism. It comes with the territory, he says, especially where social media is concerned.

Boyle County Sheriff Derek Robbins says his agency is used to public criticism. It comes with the territory, he says, especially where social media is concerned.

“But, an accusation that’s particularly upsetting — they’re saying we are targeting the Black community,” Robbins says, from inside a courthouse office. He came with a folder containing federal and state statistics, as well as arrest numbers for his agency.

“I pulled reports from the FBI Crime Reporting Statistics, and the U.S. Census Bureau, along with some from the Kentucky State Police reporting system, where we turn in all of our enforcement actions. I wanted to see for myself — are we unproportionately targeting the Black community?”

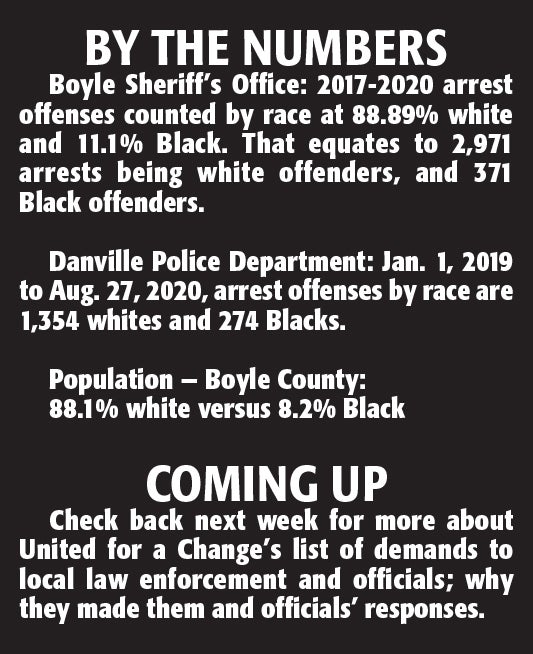

Robbins shows the Boyle Sheriff’s Office 2017-2020 arrest offenses counted by race, from the KSP’s reporting system, at 88.89% white and 11.1% Black. That equates to 2,971 arrests being white offenders, and 371 Black offenders.

He says he wasn’t surprised with what he found because he was already familiar with Kentucky’s population stats. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the state is 86% white and 7.9% Black. Boyle County is similar, at 88.1% white and 8.2% Black.

“It’s not something where we’re looking at different races and choosing to enforce different things. What we’re charging is in direct proportion to what the population is.”

Robbins says he decided to do the research on his own, and that the agency has received no formal complaints about racial profiling or otherwise targeting a certain community. Most allegations have been made via social media and circulated.

“This is the most divisive I’ve ever seen things … And I’ve been in public service most of my life,” he said.

Robbins became an EMT after college in 1997, then began his law enforcement career at Danville Police Department in 2002; he’s been with the SO since 2005.

“I went to school here, I grew up in this community. That’s not something we’re going to tolerate.”

Robbins was asked where he feels the frustration against deputies is stemming from.

“A lot of the frustration is that law enforcement, as a whole, is being blanketed as bad, because of the George Floyd incident. Not one person I know condones that.”

He says as soon as he viewed the video, “I was like — that officer is in trouble. You can’t do that. We’re not taught to do that. I don’t know what they’re taught in Minnesota, but we’re not taught to do that.”

Robbins says vilifying law enforcement for the actions of single individuals on other forces won’t make things better. He doesn’t blame Black Lives Matter “for what Antifa is doing in Louisville or Portland or Seattle. I know that’s not what (BLM) is doing, or the United for Change group (in Danville). Some people put them in that category, but I don’t categorize that (violent) behavior with what they’re doing here, and I don’t think they condone it.”

—

Boyle County Sheriff’s Office is known for its drug investigations, which the agency posts results of on social media after a big bust. A lot of the viral criticism describes deputies pulling vehicles over for minor infractions that result in drug-related arrests, with claims of racially profiling those drivers.

“Yes. Most of our charges are based on drugs, for both races,” Robbins said. He strongly refutes anyone is being pulled over or investigated because they are Black.

For the last three years, the KSP stats show drug arrests in Boyle at 432 white and 77 Black.

“There are so many variables that go into it. Ride down the road, yourself, and look at the car in front of you, daylight or darkness, and tell me if you can tell if that person is white, Black or Hispanic. It’s not plausible.”

Robbins says the majority of the SO’s traffic stops are based on investigative information — whether that comes from informants, or a specific place being watched for narcotic activity.

He says if a deputy sees a car leaving a known “drug house” and traffic-stops them, “yes, we’re going to investigate that because you just stayed a minute-and-a-half at a drug house. Or, we may have just received a phone call that says this vehicle is involved in selling fentanyl.”

A lot of their traffic enforcement is an investigative technique to catch dealers, he says, and that they are the ultimate targets of the SO. “That’s our whole goal, to take as many drugs off the street as we can so it’s not distributed to our families or kids.”

He says when they post the bigger arrests on social media, where thousands of dollars’ worth of drugs are seized, “we’re criticized for it, that we’re unfairly targeting this person because of race or because they’re poor. It doesn’t matter what your background or ethnicity is — if you’re selling that poison here, we’re going to enforce the law. That’s no Black or white issue, it’s a legal issue. Drugs are destroying families.”

He says it’s also impossible to put all the details of an ongoing case on social media. “There are variables that went into that … that we can’t put out there. There’s more that went into making that vehicle stop than no turn signal or speeding.”

But, some of the posts against the SO are “getting out of hand,” Robbins says, like someone posting that “Boyle SO is a legal name for KKK.”

Another post said if you see someone pulled over by law enforcement, pull over and get out and “check on them, and make sure they’re OK,” which Robbins says is a really bad idea. This will cause complications during a dangerous time, he says.

“As an officer, you don’t know what the person you’ve stopped is thinking, if they’re armed and just committed a crime they may think you know about it and are prepared to assault …” He says if another citizen pulls up, it causes distraction on many levels.

“You have cars whizzing by your backside, you’re trying to watch for traffic while talking to the person you pulled over. Now you have to worry about the intentions of the person who pulled up behind you, which can create a traffic hazard because oncoming cars may not see your lights … I don’t advise doing that one bit. Park somewhere else and video it, do what you’ve got to do, but don’t pull up on a scene and think you’re doing something good. Because more than likely, it’s going to cause a confrontation because you will be asked to leave.”

Robbins says he encourages open dialogues, instead of what he calls false accusations started online which create even more divisiveness as they are argued over. “I think that’s a lot of the problem. There’s a lot of accusations being made with no proof at all. I’m willing to speak to someone and say, ‘you show me the proof that this is going on, and I can guarantee you that I’ll address it.’”

Robbins uses an example of someone claiming a deputy planted drugs during an arrest. “Why would we want to plant something? We’ve got enough to deal with than to create our own cases that don’t exist.”

He credits United for a Change — Danville for setting up a meeting with him recently, which he says was a productive exchange of ideas. He says he is also 100% for purchasing body cameras for his deputies, which will require some fundraising due to the expense of not only the cameras, but yearly storage costs for videos.

“The Change group, the majority of the people involved in that legitimately want to work together to create a better dialogue between law enforcement and the Black community. And I want that as well, and am more than willing to do what I can to make sure they understand why we do what we do, and what can we do differently to make them feel more comfortable and less targeted.”

He says ultimately, “there’s no doubt in my mind that we can do things differently … but it’s got to be a two-way street. … I want to be safe, too, and want you to be safe and feel safe.”

—

Robbins says the SO is also able to do “a little more enforcement because we’re not as call-driven as the Danville PD.”

Asst. Police Chief Glenn Doan says that from Jan. 1, 2019 through Aug. 27 of 2020, they have arrested 1,354 whites and 274 Blacks. “I found it interesting that 98 of the 274 were us just serving warrants that had been issued by the court,” he said.

Doan said their officers are also encouraged to use courtesy notices, when someone is pulled over but no ticket is issued. It doesn’t always happen, due to time constraints, but regardless of whether a notice was issued, if someone feels they were unfairly targeted, “we can pull the body and dash cams from that unit, review the situations.”

Doan said he and Chief Tony Gray look at every citation, report and arrest the agency makes. “We look for any patterns …” he says, and that any assertion that they profile anyone “is completely false.”

“That’s our job, to make sure those things are happening, and I feel very confident in our agency … Now, are we going to make mistakes? Every police agency is going to make mistakes, but we want to limit those. Make sure they’re not a Civil Rights violation, a use of force situation, but we really don’t have any of those incidents. Where there’s an allegation, we’ll investigate fully and do what needs to be done to take care of it.”

Doan explains information he had prepared for the Citizens Academy, a multi-week class introducing people to how local law enforcement operates. “I’ve been pulling numbers for response to resistance, which means there was some sort of incident where we had to use force, whether it was a taser, pepper spray or a police hold, and this year, we’ve done 13 — nine white males, one white female and three black males. That’s out of almost 14,000 different contacts with citizens, 13 times.”

Sheriff Robbins says productive change won’t happen “until we have the ability to dialogue back and forth with each other. All of us should figure out a way to work together, so that we can get a better understanding of what each of us needs to be successful or make the other feel comfortable. It’s not feeling very comfortable right now.”