‘A little more local flair’: Circle G Farms sees increased interest in local farms during pandemic

Published 9:34 am Friday, April 2, 2021

- At their farm at 685 Quarry Road in Danville, the Guinns raise cattle for beef production, row crops, produce and flowers. - Photo by Olivia Mohr

Still Farming

Spencer and Carly Guinn own and operate Circle G Farms at 685 Quarry Road, where they also raise their two young daughters, Ella, 7, and Kayla, 5.

The married couple has been farming together for about 10 years — they started in Pulaski County in 2011 and bought their farm in Boyle County in 2012. They began with raising cattle and row cropping, and now they’ve expanded onto their fourth year of produce production. They’re “dabbling” into flowers and pig raising too, and they grind up corn into cornmeal.

Production of crops and caring for livestock hasn’t stopped during COVID-19 — tending to growing things and animals is ongoing.

“We were fortunate to be considered essential,” Spencer said.

The Guinn family, from left: Carly, Ella, Spencer and Kayla Guinn are in front of the barn at their family farm, Circle G Farms. – Photo by Olivia Mohr

In business they do directly with customers one on one, like selling produce and freezer beef, they actually saw an increase in sales. As terrible as COVID-19 is, Spencer said, it pushed people to want to see where their food comes from and what was going on at local farms, especially during the meat shortage that hit grocery stores.

“It brought a little more local flair to things, it seemed like, so we ended up doing more of that last year than in years past,” he said.

However, there were a few things even on their local farm that the pandemic hit. Though they saw more customers buying produce directly from them, they also sell to schools and restaurants, and with restaurants closing or switching to carryout and changing their menus, the “restaurant side really curbed off,” Spencer said. A couple of restaurants that use the Guinns’ tomatoes are Melton’s Deli locally and Ramsey’s in Lexington.

There were other facets of their farming that were slow too, such as materials used for cattle feed like corn and soybeans. There was less demand for those materials since livestock sectors were hurting due to the pandemic’s impact on processing plants, so there wasn’t a lot of demand for feed.

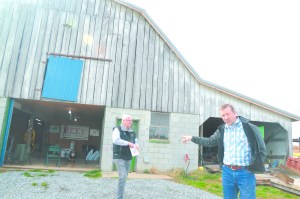

From left: Kentucky Farm Bureau president Mark Haney and Spencer Guinn at Circle G Farms. Spencer explains that the barn on the land used to be a dairy barn before he and his wife, Carly, bought the farm. – Photo by Olivia Mohr

Kentucky Farm Bureau president Mark Haney said when the pandemic hit, there was a build up of meat production that was going to institutions like schools and universities. But institutional meat cutting was shutting down due to low demand, so those institutional cuts had to go back to meat plants and be re-cut. The thing is, Haney said, that the cut for institutional meat is different from what one might find at the grocery store or on local farms — they’re usually larger, leaner and cheaper. So by the time those institutional cuts went back to meat processors, the pandemic had hit meat processing plants, causing them to shut down.

“It was a perfect storm right there that created the shortages,” Haney said. “It wasn’t because we didn’t have meat. It was because it was the wrong place cut the wrong way, and COVID was shutting down those meat packaging places. That was a true disruption right there.”

With the meat shortage, though, Haney said it made people more aware there was fresh meat available at local farms. That, along with an increased interest and awareness of fresh produce available on a local level, drove people to farms.

“And a lot of people really hadn’t had the availability or hadn’t realized it was out there,” Haney said. “Now they’ve got a taste for it, and I think it will continue.”

Carly said another market the pandemic hit was flowers — the Guinns had decided around January 2020 to start producing flowers and formed connections with wholesale florists, but during the pandemic florists weren’t doing weddings or funerals, so “that market kind of depleted.”

On top of their farming operation, Spencer and Carly both have full-time jobs, and both are related to agriculture. Spencer works for the Kentucky Center for Agricultural Development, which helps farmers around the state with their business plans and offers services for free. Carly works for Hallway Feeds, a family-owned equine feed mill in Lexington.

During the pandemic, she said, “We are fortunate. Animals always have to eat, so we always have to make feed.”

The mill produces premium quality horse feed, she said. In fact, they’ve fed 13 of the past 22 Kentucky Derby winners. Also, since racing in the Derby has still gone on, though without the crowds, the mill has continued to feed racehorses. It also continues to feed foals being bred at broodmare farms. One thing that has been impacted, however, are tours at the mill, which have “reduced drastically.”

When it comes to their family farm, Carly said farming has been a good thing for their daughters. They got pigs for them to show, but with the pandemic they weren’t able to show them. However, they were able to sell the pork, and Carly said she and Spencer are teaching the girls some business savvy. They’ll get pigs again this year. Ella and Kayla said they enjoy adventuring on and around the farm, and they have many “hideouts” in the surrounding woods. They help plant, have watched calves be born and help out around the farm.

Haney, Spencer and Carly all have agricultural backgrounds. Haney said growing up on a farm is special, and he said about the Guinns’ daughters that “They’re going to be well-grounded for many, many years.” Spencer grew up on a small farm in Pulaski and Wayne County raising tobacco and beef cattle, and Carly comes from an agritourism background — she grew up on an apple orchard in Ohio.

The “experience” farms offer to customers is something local farms and farming programs market to people — customers can come and meet the people who raised the food, pet animals and maybe even pick out their own vegetables or fruits. If farmers can offer cut flowers and other items, that only enhances the experience, and often customers are willing to pay more for the local food and the farm experience, Haney said.

Kentucky offers multiple support systems for farmers, Haney said, such as not only the Kentucky Farm Bureau and the organization Spencer works for but also the Boyle County Extension Office and the Department of Agriculture on the state and national level. During the pandemic, Haney said the Farm Bureau spent a lot of time on lobbying efforts in Frankfort and Washington, D.C. It also has a Certified Roadside Farm Market, through which more than 100 farms around the state work together to market and share.

The Guinns don’t participate in farmers markets simply due to time constraints, but they do participate in something Spencer said is quite unique to Boyle County — The Wilderness Trail Farm Share. This is a Community-Supported Agriculture program they’re part of along with about four other local farms. The farms plan what they’ll produce and provide weekly seasonal baskets from May to August. This year, pickups will be at the Boyle County Extension Office on Mondays from 3-5 p.m.

Learn more about Circle G Farms and the Guinns on Facebook @CircleGFarmKY, and learn about the Wilderness Trail Farm Share and how to sign up here.