Taking steps together: Recovery housing program organizers say more layers treating women’s addictions than men’s

Published 10:00 am Friday, July 9, 2021

After opening its doors in April, the Shepherd’s House Women’s Recovery Housing Program is in full swing with six women enrolled and living there. However, organizers say there is still much work to do in order to offer the same recovery possibilities to women that are out there for men.

Roger Fox, director of community outreach for Shepherd’s House, says they could’ve opened it up for a men’s transitional home, but he didn’t want to. Fox, along with VP of Housing Christian Countzler and house manager Olivia Eastham say there are few opportunities locally, even regionally, for women in need of sober living assistance who are going through a rehabilitation program.

“It was just time,” Fox says. “We needed it here.”

♦♦♦

Situated on an 11-acre farm sitting back off Lebanon Road, the grounds are massive with a long driveway bordered by lots of greenspace, which is helped to maintain by the inmate work program at Boyle County Detention Center.

The property is owned by the Boyle County Industrial Foundation and leased to SH at no cost, much like the same agreement with the former men’s transition home there which closed.

The community center has a huge open room on the first floor, with Eastham’s living quarters upstairs. There’s also an unused garage they plan to turn into a safe space for supervised visits between moms and children, thanks to a private donation and possible future funds from Boyle County ASAP.

The women are housed just next door. Upstairs, the first room full of bunkbeds is called Phase 1, and as they progress, women are able to move into the last, nicer room which holds only two beds, or Phase 2.

“This has all been a big learning experience for us …” Fox says, as this is the first women’s home opened by SH. There are additional layers to think about in women’s recovery, he says, “like domestic abuse, kids being in the mix …”

Countzler, who like others working for SH also went through rehab, says when he got out of treatment, he had his choice of sober living facilities or halfway houses, but there are “way fewer women’s facilities like that.”

Eastham says a huge factor in women’s recovery is their children and other family responsibilities. “They feel selfish getting help instead of taking care of their children.” But here, she says, they learn that’s not so.

♦♦♦

“My younger children are with their father, am hoping they can come see me, eventually …” says Tracy Mullins. She had already done a stint in rehab, but says she knew 28 days wasn’t enough. Starting with pills, she eventually turned to meth and was hooked for five years.

With two older children, Mullins says she “started over,” and had two more later in life, now 10 and 11.

“I haven’t talked to them in two months, I think it’s better that way,” Mullins says, then looks to the side. “I know it sounds kind of mean, but I think it’s better, don’t want to give them false hope until I know I’m ready. It’s a commitment …”

Mullins already walked out once, but came back. “I know this is where I need to be. But, as a mother, I feel like I’m being selfish, trying to do this. My daughter — I guess I taught her right, she said, ‘Mom, you’ve got to do this for your younger ones, you won’t be any good for them.’”

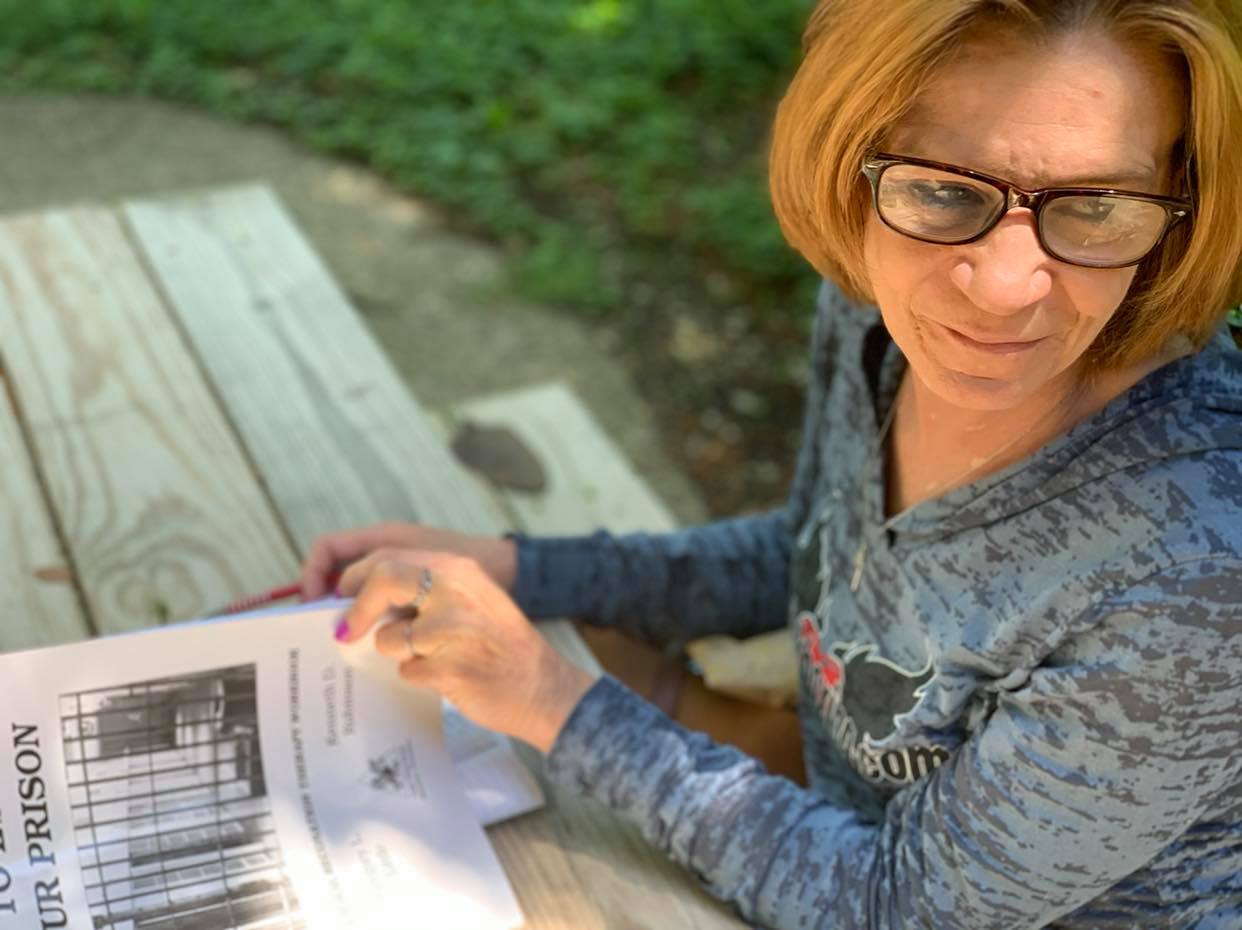

She opens her Moral Recognition Therapy handbook, part of the Jails to Jobs program through a Department of Justice grant. Holding it up, she says, “It’s called ‘How to Escape Your Prison,’ because that’s what you feel like you’re in, when you’re addicted.”

Fox and Eastham point out that the women are no longer in jail here and have freedom, but they must adhere to structure. They get up early every day, either to go to work — which they are required to do to live here — or attend group meetings and do chores around the farm. They pay $110 a week for housing, food, treatment and transportation, and no one has had any issues getting employment.

Eastham transports the women to group when held elsewhere, to therapy or jobs, and picks them up. She and Fox laugh about how he joked with her during her interview, pointing to a rundown shed on the property as where she’d be living.

“I wasn’t scared. I knew this is what I wanted to do. I knew it was going to be hard work, and I was ready for it,” she says, through a huge smile.

♦♦♦

Alicia Gilbert has been in the program for three months and loves it. She’s battled a mental condition for most of her life, now under control, which is part of the reason she turned to crack cocaine, addicted for 11 years; she was trying to numb the pain, she says.

“But it hurt me way more in the long-run,” Gilbert says. “I’ve never met my little girl, she’s 6 and with her daddy. I’m going to meet her, eventually.”

Gilbert, like the other women, found a job almost immediately after moving in, and says they are even considering her for management.

“The most important thing I’ve learned is that I’m stronger than I thought I was. It changes your life.” She says they are up every morning at 7:30 to do meditation and attend meetings, and they get help maintaining their recovery and mental health. “You don’t have enough time to worry about outside things, you work on you.”

Fox says SH is working on figuring out a Phase 3 of the program, hopefully to be an apartment that will house some of the women together, a last step before entering the real world on their own.

The program is also considering starting a steering committee, Fox says, made up of women from Boyle and Mercer counties. “We’re looking for women who want to come in and invest in these women, that’s important … help them learn how to live life normally again …” he says. “And, we can’t fit one more body into that van we use, so we’ll have to figure that out …”

Eastham, who was addicted to heroin and overdosed more than she can count, sometimes twice in 24-hour spans, says she hit rock bottom when she had to “detox real hard” in jail. She reconnected with her father, who helped her get treatment.

And he said something to her back then that still resonates with her today, and affects how she does her job. “He said when you’re ready to go to treatment, for every step you take I’ll take 10 for you. That stuck with me.”

For more on the Shepherd’s House Women’s Recovery Housing Program, including how to donate or volunteer, contact Fox at (859) 209-4244 or email rogerfox@shepherdshouseinc.com.