Looking Back at Kentucky School for the Deaf: The Colored School (1885-1963)

Published 6:00 am Monday, February 21, 2022

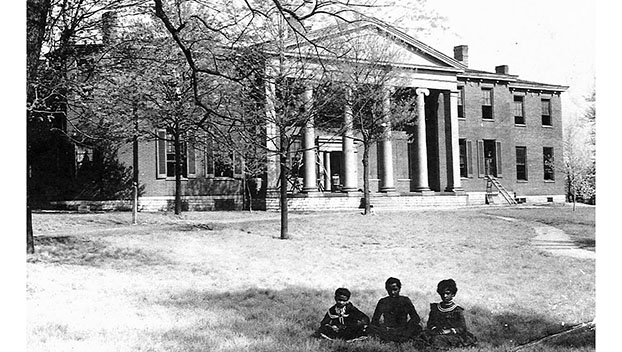

- To house the Colored School, the Commonwealth of Kentucky purchased the old Grigsby Homestead, a large two-story colonial mansion. The building’s two wings, originally one story, were expanded by adding another story in 1887. Another expansion at the south end provided a large school room on the first floor and dormitories for boys and girls on the second. In 1890, a brick addition gave the students a chapel and dining room and a playroom in the basement.

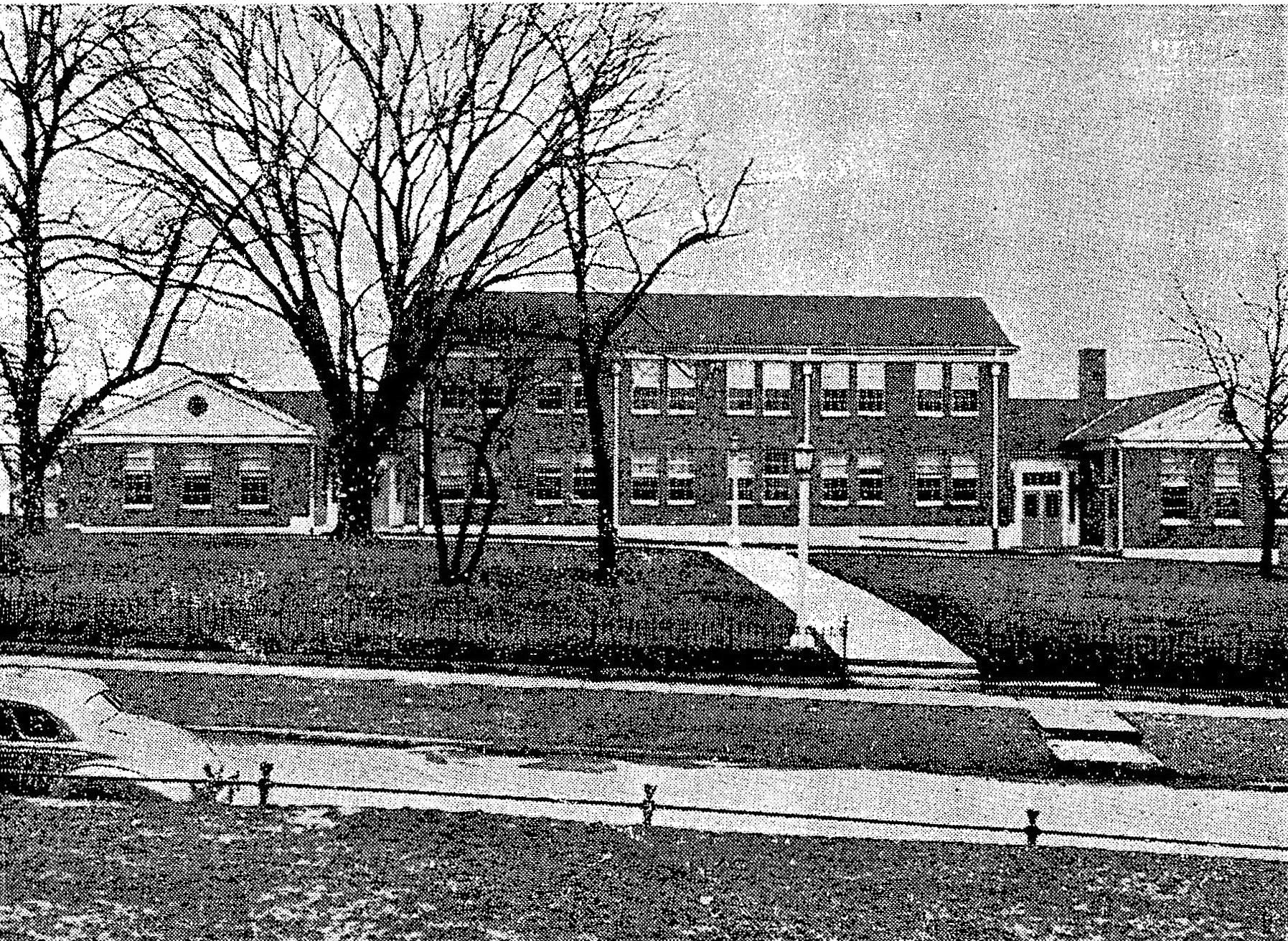

Booker T. Washington Hall stood directly across the street from the Engineer’s House (now Edward Jones). After integration it became one of the elementary classroom sites and a girls’ dormitory. It was razed in 1980 to make way for a new multi-handicapped complex, Brady Hall.

By JoAnn Hamm

Jacobs Hall Museum Staff

The first school (or department within a School for the Deaf) for African American deaf students in the American South was established in Raleigh, North Carolina in 1869, only four years after the Civil War. The third school for colored deaf students, at Kentucky School for the Deaf, opened much later, in 1885. Because of “racial purity” laws in effect in Kentucky and other areas of the South, African American students could not attend classes with white students and thus deaf African Americans needed their own school.

The KSD Colored School (as it was called) opened on February 2, 1885, twenty years after the abolition of slavery and the end of the Civil War. KSD records show that the segregated school was referred to as “the Colored School” colloquially as well as in official documents until desegregation in 1963. Initially there were eight pupils and one teacher, a deaf KSD graduate named Morris T. Long.

To house the Colored School, the Commonwealth of Kentucky purchased and refurbished the old Grigsby Homestead, a large two-story colonial mansion. The building’s two wings, originally one story, were expanded by adding another story in 1887.

An expansion at the south end provided a large school room on the first floor and dormitories for boys and girls on the second. In 1890, a brick addition gave the students a chapel and dining room and a playroom in the basement

Although this educational opportunity for deaf African Americans was a major step forward, discrimination was still very real. The daily routine in the Colored School was not the same as in the main school. While both schools sought to teach practical career skills as well as academics, the Colored School’s students tended to be taught fewer advanced subjects and skilled trades.

Charles P. Fosdick wrote in his 1923 A Centennial History for the Kentucky School for the Deaf that a handful of African American boys were noted to be of exceptional ability and could learn a trade in the white school’s workshops late in the day when the white boys were not using the equipment. He felt that deaf African Americans who were given a chance at education through the Colored School tended to be “industrious law-abiding citizens, respected and esteemed in the communities wherein they dwell.” For decades, Charles and Mary Fosdick served as boys’ supervisor and matron, respectively.

The Colored School’s largest enrollment was in October 1897, when there were fifty students and four teachers. Soon after this, enrollment began to decline and by 1909 there were twenty-three pupils and two instructors, with the same number of teachers and a roughly similar number of students in the school from that point forward until KSD integrated.

By the end of World War II, it was clear that Warrick Hall was a fire hazard, with an antiquated heating system, consisting of 28 fireplaces and stoves. Too expensive to renovate, it had to be replaced. The search was on for an appropriate site for a new separate-but-equal school. In 1950 KSD acquired the last of a series of building lots, which had been part of an antebellum estate, Breezy Hill, lying just south of the school gardens and the gardener’s house. The deal was made possible by a trade with the State Board of Health which had purchased the lots. These lots were deeded to the school by the Health Board, in return for the house and lot on the southeast corner of Third and Jacobs Street, which soon became the site of the Boyle County Health Department. In 1952, the pupils of the Colored School moved into a new 18-room building on South Second St. The building included classrooms, a kitchen wing and a dining room, an auditorium, a laundry, a domestic science kitchen, sewing rooms and parlors. There were quarters for the matron and supervisors as well. Directly behind Washington Hall was a small shop building where trades could be taught.

Integration began after the Landmark Supreme Court Decision: Brown vs. the Board of Education of 1954. Initially black and white students were taught in the same vocational classes. From 1959 to 1960, academic classes were integrated. By 1963 all dining halls and dormitories were integrated, and the “Colored School” was no more.