Study says Kentucky’s 50th Circuit Court has been discriminating against poor defendants, but things may be changing

Published 5:43 pm Friday, November 16, 2018

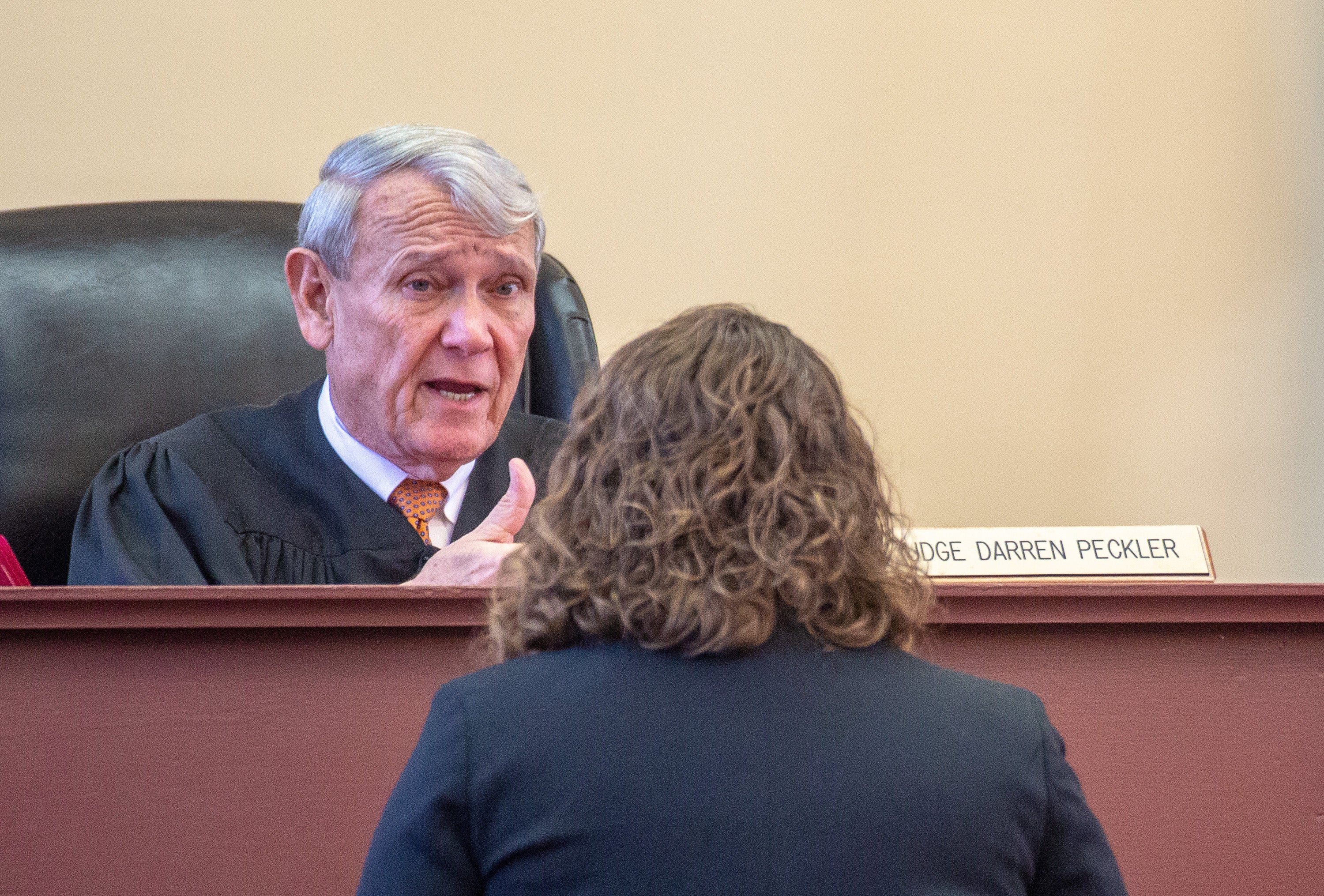

- Ben Kleppinger/ben.kleppinger@amnews.com Circuit Court Judge Darren Peckler speaks with Public Defender Jessica Buck during an Oct. 16 circuit court date in Boyle County.

Boyle County Circuit Court Judge Darren Peckler looked through the case file, then down to the attorney standing in front of his bench.

“We’re asking the court to release him on an unsecured or ROR bond or allow his mother … to sign a surety,” Public Defender Jessica Buck said.

Buck’s client, Enic Anderson, was facing a criminal abuse charge.

“Is this his fifth felony?” the judge asked.

“It is, your honor,” Buck answered.

The next question: “Is there another charge pending against him now, too?”

“No, your honor,” Buck said.

“My report indicated that there was another …”

As Peckler sifted through his documents again, Buck told him Anderson had previously been out on bond at the district-court level, until he was indicted by a grand jury and re-arrested; no other charges were pending.

“Ms. Buck, that’s not what I remember,” Peckler said.

Buck said a pretrial report on Anderson did initially indicate a pending charge in Lincoln County, but “in my motion, I made it clear that was an error” that had since been corrected.

Buck filed her motion 13 days earlier, asking Peckler to reduce Anderson’s $5,000 cash bond, arguing it was excessive and unconstitutional to hold her client on a bond he couldn’t pay. She sought a non-financial bond so that Anderson could leave jail without paying money.

The motion argued state law, Kentucky Supreme Court precedent, the Equal Protection Clause of the U.S. Constitution and the American Bar Association’s standards for pretrial release are all on the side of pretrial release for low-risk defendants, whether they have money or not.

Further, a local study commissioned by Boyle and Mercer counties’ fiscal courts blamed the handling of cases like Anderson’s for overcrowding the local jail, Buck argued in the motion. “One of the suggestions was not to re-incarcerate individuals like Mr. Anderson, who were successfully out on bond, simply because they have been indicted by the grand jury. Now, more than ever, the law and public policy supports the release of Mr. Anderson.”

In Peckler’s courtroom Oct. 16, the judge agreed Buck had explained the mistake about a pending charge in her motion. But he wanted to see a new pretrial report completed before he made any changes.

“Let me look at the report from them, and I’ll take that under advisement and be happy to consider a 10-percent bond for him or some other reduction,” Peckler said.

“If the court will not grant our motion just based on this brief argument, I’d ask for a full hearing at which my client would have a right to be present,” Buck responded.

“Certainly, certainly,” Peckler said. “I’ll let you know about that. I don’t see any reason I can’t put it at 10 percent, but I do want to look at what happened on another charge or what they said the other charge was.”

After the Oct. 16 court date, Anderson’s bond was reduced — not to an unsecured or ROR (“released on own recognizance”) bond as requested in Buck’s motion, but to a $5,000, 5-percent bond, meaning Anderson had to pay $250 for his release. He got out of jail the next day, after paying the $250 and a $25 bond filing fee, for a total of $275.

Anderson’s was one of multiple cases heard during Peckler’s Oct. 16 circuit court date where the judge sparred with public defenders over financial bonds. But the fact he’s out of jail now means Anderson’s case may also be part of a new trend in Peckler’s court that is leading to more defendants being released pretrial.

‘Jail is greatly bloated’

Kentucky’s 50th Circuit and District courts, which handle cases for Boyle and Mercer counties, have offered defendants non-financial bonds at the lowest rates in the state for years, according to data from the state Administrative Office of the Courts.

The AOC Department of Shared Services produced a statistical report earlier this year, showing that statewide, defendants in criminal cases were offered non-financial bonds — a chance to get out of jail while still considered innocent without paying money — about 39 percent of the time in 2017. In Boyle County, the rate was about 4 percent; in Mercer it was 7 percent.

The final, 349-page version of the local study Buck referenced in Anderson’s case was released Nov. 9. It blames “discriminatory” bond practices and lethargic case-processing times in Peckler’s court as culprits responsible for overcrowding at the Boyle County Detention Center.

“The jail is greatly bloated by three factors: (1) very slow felony case processing, (2) an apparent refusal to set non-financial bonds, (3) a very high incidence of revocation of initial bonds and rearrest after being indicted by grand jury,” the report states.

Anderson’s case is perhaps an example of all three factors.

The case against him involves an incident where his son was found wandering alone in Junction City while wearing only a diaper, according to court records.

Anderson was asleep at 10 a.m. on June 5, when “his 2-year-old son exited the residence and walked to an apartment complex, knocking on doors until (a resident) made contact with the child,” according to Anderson’s arrest citation.

Anderson was charged with first-degree wanton endangerment, a Class D felony, and lodged in the Boyle County Detention Center. He was given a $20,000, 10-percent bond at the district-court level, meaning he would need $2,000 to get out of jail while his case was pending. At the district level, defendants are often given “bail credit” of $100 a day; after 19 days in jail, Anderson had $1,900 in bail credit. He paid $100 and a $25 bond filing fee and was released on June 23, according to court records.

A Boyle County grand jury then indicted Anderson in the case, but modified the charge to second-degree criminal abuse, also a Class D felony. Peckler set a new bond for Anderson at $5,000 cash. Anderson hadn’t done anything to violate the terms of his district bond, but he was re-jailed on Aug. 6. He spent the next 73 days in jail.

The local study, compiled by consulting company Brandstetter Carroll at a cost of $75,000, details how Peckler “consistently” sets cash bonds for everyone indicted on a felony charge — $5,000 for Class D felonies and $10,000 for Class C.

“Bail credit, surety bonds or release on own recognizance (ROR) bonds are not utilized in Circuit Court,” the study states. “… The judge is, in essence, acting as a magistrate to set bonds anew. In doing so, he is disregarding evidence of success of defendants who appeared in court and remained crime-free while out on pretrial release under bond set by the district judge. As a result, more defendants cannot afford the new bond.”

The study notes a caveat — “in the last several months, the defense attorneys have advocated for pretrial release on ROR, unsecured bonds and lower bonds. The attorneys have addressed Kentucky Court Rules that emphasize pretrial release and the use of non-cash bonds. As a result, the circuit court judge has altered his pattern of setting bonds.”

‘Seems like a waste’

Public Defender Buck said she agrees with the study’s recommendation that Peckler’s court stop requiring new bonds for everyone indicted by a grand jury. But she also acknowledged court precedent is clear that nothing is legally being done wrong when someone is re-arrested after indictment.

“I don’t think that anybody who is successfully out on their bond conditions out of district court should be re-arrested simply because they’re indicted by a grand jury,” she said.

Anderson’s mother, Carol Caldwell, wrote Peckler a letter while he was in jail, pleading her son’s case to the judge.

Anderson had been “compliant with all urine screening” required by his bond at the district-court level, she wrote. The mother of Anderson’s son was supposed to be watching the child at the time the incident occurred — Anderson “had worked all night installing a floor in Nicholasville” and was asleep when the child left the home, wrote Caldwell, who works as a deputy at the Boyle County Detention Center where her son was incarcerated.

The mom and child weren’t supposed to be staying with Anderson at all, but were anyway because they were otherwise homeless, Caldwell wrote.

“Being that (the mom) only received a 2-year pretrial diversion for the same crime and same incident, I am graciously asking the courts to consider the circumstances surrounding the incident,” she wrote.

Anderson himself also petitioned Peckler from jail.

“I am writing you in my behalf to ask for a 10-percent bond,” Anderson wrote in a Sept. 15 letter. “My bond is now $5,000 cash. I was out on bail credit in district court and was fully compliant with conditions of bond. And (I) was also taking weekly drug screens for DCBS with negative drug screens.

“… I am asking you for a 10-percent bond so I can get back to work to support my family … so I can get back to work and move forward in being a productive member of the community.”

Buck, who spoke in her individual capacity as Anderson’s lawyer and not as a representative of the Public Defender’s Office, said Anderson’s time in jail has made things difficult for him after his bond was lowered and he was able to get out.

Anderson is a self-employed handyman — “He does flooring and kind of odds-and-ends sort of stuff,” she said.

“Obviously, he was unable to support his family while he was incarcerated and being self-employed, it’s even harder to rebuild that,” she said. “The reputation you build in the community when you’re self-employed — and then all of a sudden, you disappear for two months or three months, it makes it harder for him to get jobs in the future.”

Buck said that also makes it harder for Anderson to pay any child support he owes.

“I’m not sure what the community got from incarcerating Mr. Anderson for another two months,” she said. “I don’t see how it made the community safer or how it helped reunite Mr. Anderson and his children. It just seems like a waste of taxpayer money.”

Anderson is hoping to get back to normal — there’s been an offer made in his case of a misdemeanor charge. “We’re considering that offer and in negotiations,” she said.

In November, Anderson’s case was continued to January while those negotiations continue.

“What is nice is because Enic is out on bond, we’re able to take time and engage in longer negotiations and more investigation than when a client is in custody,” Buck said, adding that defendants who are unable to leave jail often feel “pressure” to resolve their cases — sometimes with less favorable pleas.

While he waits for his case to resolve, Anderson is working a case plan so he can maintain a connection with his son.

“I talked to his mom the other day and she was talking about him building a tricycle with his son and working on the case plan,” Buck said. “He is trying to start work back up.”

Changes are happening

Buck said she has witnessed the recent changes in bonds noted in the study firsthand.

“I will say that there have been significant changes lately, particularly in circuit court,” Buck said during an interview about the case against Anderson. “This month (October) was one of the first months that I had more people released … than stayed in custody (after their arraignments).”

Buck said she is glad to see positive changes being made.

“I don’t know why it’s occurred, but I can say the fact that it has occurred — credit goes solely to Judge Peckler, because he is in charge of setting the bonds,” she said. “So something has happened that he is setting more reasonable bonds, which is a vast improvement.”

The changes in Peckler’s courtroom may be reflected in the Boyle County Detention Center’s population, which has been in the 220s multiple days this month, after peaking at more than 400 inmates multiple times in 2017.

“I guess there’s a lot of get-out-of-jail-free cards right now, I don’t know,” Jailer Barry Harmon said. “It’s nice. It sure makes a quieter jail.”

On Nov. 15, the population even dipped below the jail’s rated capacity of 220, hitting 217 inmates at about 10:30 a.m. An analysis of jail records by The Advocate-Messenger identified 27 inmates out of those 217 who were facing non-violent, non-sexual charges and being held on financial bonds at the circuit court level. Six were being held on $5,000 cash bonds; eight on partially secured $5,000 bonds; two on $10,000 cash bonds; two on partially secured $10,000 bonds; and 11 on other secured bonds. Two inmates with financial bonds were not counted among the 27 because they were facing fourth-degree assault charges.

The analysis found one inmate being held on an unsecured circuit court bond and 14 more being held without bond from circuit court, mostly for contempt of court charges. The local study has also recommended considering more alternatives to re-incarceration when defendants fail to appear for a court date.

The analysis did not count inmates who had been sentenced; inmates who had bonds set only at the district-court level; or inmates who were being held on no bond at the district-court level or from another jurisdiction.

While the jail is rated to hold 220 inmates, the local study notes that the real “operational capacity is 176. Average daily populations exceeding 176 put the jail in a gray area with regards to constitutional rights.

“A jail’s operating capacity should accommodate the peak populations to ensure provision of constitutionally adequate levels of confinement, even when confinement is temporary or short-term,” the report states. The jail has been “unable to accommodate peak populations for at least the past 16 years.”

The study recommends construction of a new 450-bed jail to accommodate inmate population projections over the next 30 years. It also suggests a larger, regional facility would be possible if Boyle and Mercer counties could partner with other area counties, such as Lincoln and Garrard.

Peckler would not comment on the recent changes in bonds for this report. The Advocate-Messenger delivered a letter to Peckler’s office on Nov. 2, asking for an interview concerning the use of financial bonds in his court and how his use of them is changing. As of this week, Peckler had not responded. Peckler has not responded to previous interview requests made by the newspaper concerning financial bonds in September 2017, June 2018 and September 2018.

Boyle County officials attempted to involve Peckler in development of their study. In November 2017, Boyle County Deputy Judge-Executive Mary Conley said she was unable to get Peckler on-board with the idea of having a judge on the counties’ Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, a group intended to guide development of the study and help implement its recommendations when final.

“He was pretty adamant that there would be no (participation),” Conley said at the time. “… He thought it was putting he and his office in a possibly litigious situation. If something happened, that he didn’t want to have to be sued and be sitting on a committee that would get sued. I didn’t quite understand.”

Consultants working on the local study went over tens of thousands of documents and jail records and conducted dozens of interviews with people involved in the local criminal justice system at every stage — except, notably, not with any judges.

“Unfortunately, the Circuit Court Judge (Peckler) refused to participate in the study and prohibited the District Court Judge (Jeff Dotson) from participating,” the report states.

Boyle County Judge-Executive Harold McKinney said in October he would send a letter to Peckler, inviting him to address the study’s findings “in whatever format” the judge preferred. “I think he needs the opportunity to formally respond, whether it’s in a public forum, whether it’s (before the local Criminal Justice Coordinating Council), whether it’s in writing.”

McKinney said Nov. 13 he had not received a response from Peckler.

Not the norm for Kentucky

The local study found that the combination of delays in case processing and the use of financial bonds in the 50th Circuit Court led to many defendants remaining in jail for the duration of their case.

“An estimated 80 percent of low-level felony defendants who receive a one year sentence will have served a ‘state year’ (about seven months) at time of sentencing,” the report states. “The answer to the question of ‘Why does this happen?’ may lie in the discriminatory manner in which bonds are set, i.e. economically-able defendants are able to post bond, while the less affluent stay in jail.

“The fact that the poor stay in jail does not mean that they are greater risks for failure to appear or of committing new offenses while on pretrial release. Many court cases and a volume of research attest to the discriminatory nature of blanket application of secured (financial) bonds.”

The study looked back at the setting of circuit court bonds over the last eight years in Boyle and Mercer counties, as well as in 12 other Kentucky counties with similar populations and criminal case loads. It found Boyle and Mercer were dead last in offering non-financial bonds, at 4 and 3 percent of the time, respectively.

By comparison, Clark County defendants got non-financial bonds 18 percent of the time (the next-lowest rate); Lincoln County was 28 percent; Harlan County was 55 percent.

“It is unlikely that the release recommendations made by Pretrial Release interviewers in Mercer and Boyle counties differed so greatly from the comparison counties as to be the cause of judicial decision-making about non-financial bonds,” the report states. “It is difficult to avoid coming to the conclusion that the circuit court judge does not believe in non-financial bonds.”

The report goes on to explain the many ways that defendants can be harmed when they’re kept in jail because they don’t have money:

Defendants who are detained are “more likely to be sentenced to jail or prison and for longer periods of time,” the report states. “… Contributing to the disparity in sentencing is that detained defendants are more likely to take less-favorable plea deals.”

It elaborates elsewhere: “In court systems having slow criminal case processing and few alternatives to pretrial detention, prosecutors and defense attorneys know that the pressure to plea(d) is greater for detained defendants that similar-offense defendants who bond out. Detained defendants usually are aware that ‘their choice is to take a quick plea deal and accept blame for a crime that they have not committed, or stay in jail and let their lives unravel while slow case processing runs its course.’”

A similar disparity was found when the consultants developing the local study compared Boyle County’s case-processing times to statewide case-processing standards.

Kentucky courts generally dispose of about 80 percent of their felony cases within 90 days, meaning from arrest and case filing to a conclusion takes three months or less for the vast majority of cases.

In Boyle County, only 21 percent of felony cases were resolved within 90 days in 2017. In other years, it was as low as 10 percent (2012), 8 percent (2010), 5 percent (2008) and 2 percent (2011).

About 94 percent of Kentucky felony cases are disposed of within 180 days; in Boyle County, that figure has been 62 or 63 percent for the last three years, according to the study.

“Very possibly the problem of jail overcrowding would not exist if felony case processing was just moderately faster,” the study states. “… for example, disposing of 50 percent instead of 21 percent of cases within 90 days and disposing of 80 percent instead of 62 percent within 180 days.

“Given that many counties similar (to) Boyle and Mercer counties process cases faster, such improvements should be relatively easy to achieve.”

The study’s recommendations include adding another circuit court date every month, allowing circuit court defendants to enter pleas more than once a month and eliminating Peckler’s cap on the number of pleas he will hear each month, among other things.

Pretrial risk assessment

When someone is arrested for an alleged crime and booked into a jail, a Pretrial Services officer conducts a risk assessment, according to Tara Blair, head of Kentucky’s Department of Pretrial Services.

The risk assessments are created using the Public Safety Assessment developed by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation — an assessment based on years of research and evidence that has been validated using data from more than 2 million cases in Kentucky, Blair said earlier this year. The same assessment has been statistically validated in other jurisdictions, she added.

Kentucky’s Pretrial Services has used “an objective, statistically valid pretrial risk assessment since at least 2010,” according to the Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy.

“Studies of the data of 100 percent of those released pretrial … show that persons classified as ‘low risk’ come back to court and do not commit new criminal offenses while on release approximately 94 percent of the time, and that persons classified as ‘moderate risk’ come back to court and do not commit new criminal offenses while on release approximately 88 percent of the time.”

A 2014 study by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation of Kentucky’s use of a pretrial risk assessment tool called PSA-Court found that Kentucky’s judges were able to “reduce crime by close to 15 percent among defendants on pretrial release, while at the same time increasing the percentage of defendants who are released before trial.”

During the first six months of using PSA-Court, Kentucky judges released 70 percent of defendants pending trial, up from 68 percent the previous four years, according to a summary of the study from the Arnold Foundation.

“What makes the increase in release notable is that it has not come at the expense of public safety; to the contrary, it has been achieved alongside a decrease in pretrial crime,” the summary states. “… The average arrest rate for released defendants has declined from 10 percent to 8.5 percent.”

But the risk assessments don’t preempt judges’ discretion — judges are free to set financial bonds for a moderate- or low-risk defendants if they feel it is warranted.

According to a report on “reform opportunities in Kentucky’s bail system” by the Pegasus Institute, a Kentucky-based think-tank, there were 64,123 non-violent, non-sexual defendants held in Kentucky jails in 2016 because they could not afford their bonds. “Meanwhile, 43 high-risk, violent or sexual offenders were released after posting a monetary bail.”

The Advocate-Messenger’s analysis of Nov. 15 jail records identified six inmates charged with serious sexual or violent crimes who could be released if they come up with money for their bail:

• a man charged with sexual abuse of a child under 12 has a $75,000 cash bond;

• a man charged with sodomy, incest and abuse of a child under 12 has a $100,000 cash bond;

• a man charged with first-degree rape has a $50,000, 10-percent bond;

• a man charged with attempted murder of a police officer has a $30,000 cash bond;

• a man charged with first-degree rape and unlawful imprisonment has a $20,000 cash bond; and

• a woman charged with first-degree sexual abuse of a child under 12 and promoting a minor in a sex performance has a $30,000 cash bond.

The Pegasus report calls for Kentucky to transition to a system that focuses on offenses and not on “a defendant’s financial means,” and points to a recommendation from Kentucky’s Criminal Justice Policy Assessment Council (CJPAC), which would move the state “to a more pure risk-assessment-based model and (eliminate) monetary bond for non-violent, non-sexual offenders who were assessed as low or moderate risk.”

The recommendation would “also give judges greater leeway in detaining violent and sexual offenders pretrial,” the report states. “The move would make the pretrial process in Kentucky similar to existing models in New Jersey and Washington, D.C. While both systems are complex and have faced some criticism, they have advocates that include the American Civil Liberties Union, California Senator (and former California Attorney General) Kamala Harris, (Kentucky) Sen. Rand Paul and (New Jersey) Gov. Chris Christie.”

The CJPAC recommendation would allow more low- and moderate-risk offenders out, but would “also give greater opportunities to prosecutors to request that violent and dangerous offenders be detained ahead of trial,” the report states. “This is largely what some have attributed to the near universal buy-in in the Washington, D.C., courts around this model.”

Move away from money

Everyone may not be on-board with elimination of financial bonds, but the push for bail reform has some big names in Kentucky talking, including Justice Secretary John Tilley and Supreme Court Chief Justice John D. Minton Jr.

Tilley said earlier this year at a conference on rural incarceration that legislation to limit the use of money bail “still has momentum” in the commonwealth.

“The real opposition comes from judges who think they’re having their discretion removed in terms of a release decision — that there’s some risk instrument … some machine that tells me I’ve got to release this person,” Tilley said. “… The research is very clear. The best decisions come from using science along with professional discretion. So I’ve tried to make sure judges understand nobody is suggesting they have to give up their discretion … use your common sense, you can deviate.”

“There’s a great deal of public debate regarding bail reform, both in Kentucky and around the country, as jail and prison populations continue to soar,” Chief Justice Minton said in his “State of the Judiciary” speech delivered Nov. 2. “The Kentucky Court of Justice is answering the growing call for reform by joining other states taking part in the Pretrial Justice Institute’s 3DaysCount campaign.”

Minton explained the 3DaysCount initiative is an effort to reduce the number of people in jail without “sacrificing public safety.”

“The program is based on the premise that even three days in jail can leave many people less likely to appear in court and more likely to commit new crimes because of the stress incarceration places on jobs, housing and family connections,” Minton said. “Commonsense solutions can lead to better outcomes, enhanced public safety and more effective use of public resources.”

Kentucky decided to participate in 3DaysCount thanks to its Pretrial Bail Practices Committee, made up of 14 circuit and district judges, Minton said, before cautioning that “the Kentucky Court of Justice does not make policy” and decisions “are solely within the province of the legislature.”

“I also want to stress that although there is disagreement among our judges on the best approach to bail reform, individual judges cannot and do not speak on behalf of the court system or their respective associations,” Minton said. “Despite our personal opinions on this issue, our role in this process is to provide guidance on how changes in the law will impact the court system and our Pretrial Services program from an administrative standpoint.”

In September, Minton told NPR station WKYU in Bowling Green that Kentucky is looking into alternatives to posting bail.

“We don’t need to lose sight of the number-one, bedrock principle and that is the presumption of innocence operates in every case, so that presumption does not need to be lost,” Minton told the radio station.

The 3DaysCount project says almost 500,000 “legally innocent people” are held in jail daily, costing an estimated nearly $14 billion annually.

“Most of these men and women could be released to await trial in the community and be counted on to appear in court and not be arrested on new charges while their case is handled. They remain detained solely because they are unable to afford money bail,” according to a release from 3DaysCount. “Letting access to money decide who gets detained before trial lets wealthier people purchase their freedom — regardless of the danger they pose to individual and community safety — while poor and working-class men and women remain in jail even if they have been arrested on low-level, non-violent charges.”

SO YOU KNOW

The study of the Boyle County Detention Center and the local criminal justice system was compiled over the course of about a year by consulting company Brandstetter Carroll. Boyle and Mercer counties paid Brandstetter $75,000 for the study in order to determine what to do about their aging jail and its growing inmate population.

Dr. Allen Beck and Dr. Kenneth Ray were two of the lead consultants. Beck has a doctorate in criminal justice and has a lengthy career working on jail projects across the nation. Ray is a mental health and substance abuse expert.

This article focused largely on the findings and recommendations made in chapter 2 of the study. Watch for articles on other chapters in the study in future issues of The Advocate-Messenger.