‘We have done the work’: Danville African American history is focus of international design competition project

Published 1:08 pm Tuesday, October 27, 2020

What used to be a thriving African American business district along and around Second Street in Danville and is now Constitution Square is the focus of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University’s project for an international design competition called Tactical Urbanism Now!, of Terraviva Competitions.

According to the competition website, the challenge of the competition is “to encourage participants to imagine a city where public space goes beyond the traditional conception of a park, a square or a street” by implementing multifunctional urban designs to promote social exchange, interactions between citizens and community activity. Submissions for the competition are due at the end of November, with competition results in December, according to the competition website.

N.C. A&T is the number one public historically Black university in the nation, according to the university’s website, and William Harrison, assistant professor/coordinator in the landscape architecture program at N.C. A&T, said pursuing the project with a focus on the historical business district is meaningful to the university.

“It is the mission of our program to provide a unique framework for studying landscape architecture, which is carried forward in service-based learning projects that focus on underrepresented populations,” Harrison said in an email. “These projects mean everything to our program.”

The university has partnered with Gresham Smith in Louisville, a team of designers that work with cities and towns. This team has worked with the City of Danville on its downtown master plan strategies, and the university partnered with Gresham Smith after the university began an affirmative action initiative and Gresham Smith reached out to become a partner, Harrison said. Then Gresham Smith proposed working together on the tactical urbanism competition with a focus on Danville’s Second Street historic African American business district. The Danville-Boyle County African American Historical Society, the city of Danville and the Danville/Boyle County Convention and Visitors Bureau are also partners on the project. Harrison said at the university, the competition is built into a sophomore studio, and there are eight students from N.C. A&T involved in the competition.

Jennifer Kirchner, executive director of the CVB, said tactical urbanism has some of the same principles as placemaking and allows for projects that are more temporary or are easier to implement that add to a community, like a painted crosswalk, parklets or other projects. Tactical urbanism could, for example, also involve using 3-D printed models or augmented reality to tell a story of a place. The work and ideas behind this specific project are not something that can be shared in detail due to the competitive nature of Tactical Urbanism Now!, said Louis Johnson, an urban designer for Gresham Smith in Louisville.

Kirchner said the project gives her hope for the future. She is also hopeful that the project could be funded with grants or could be funded by raising money locally, though she’s not sure yet of the cost.

“This is a project that listens to people, engages the community and tries to put forth a way to honor and to save and preserve what came before,” Kirchner said.

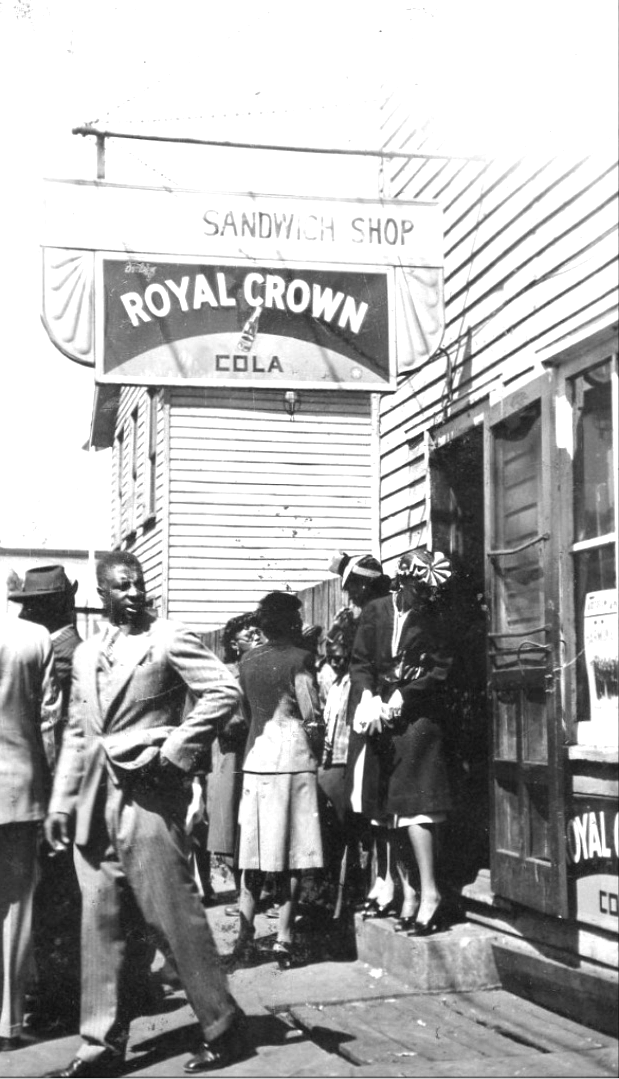

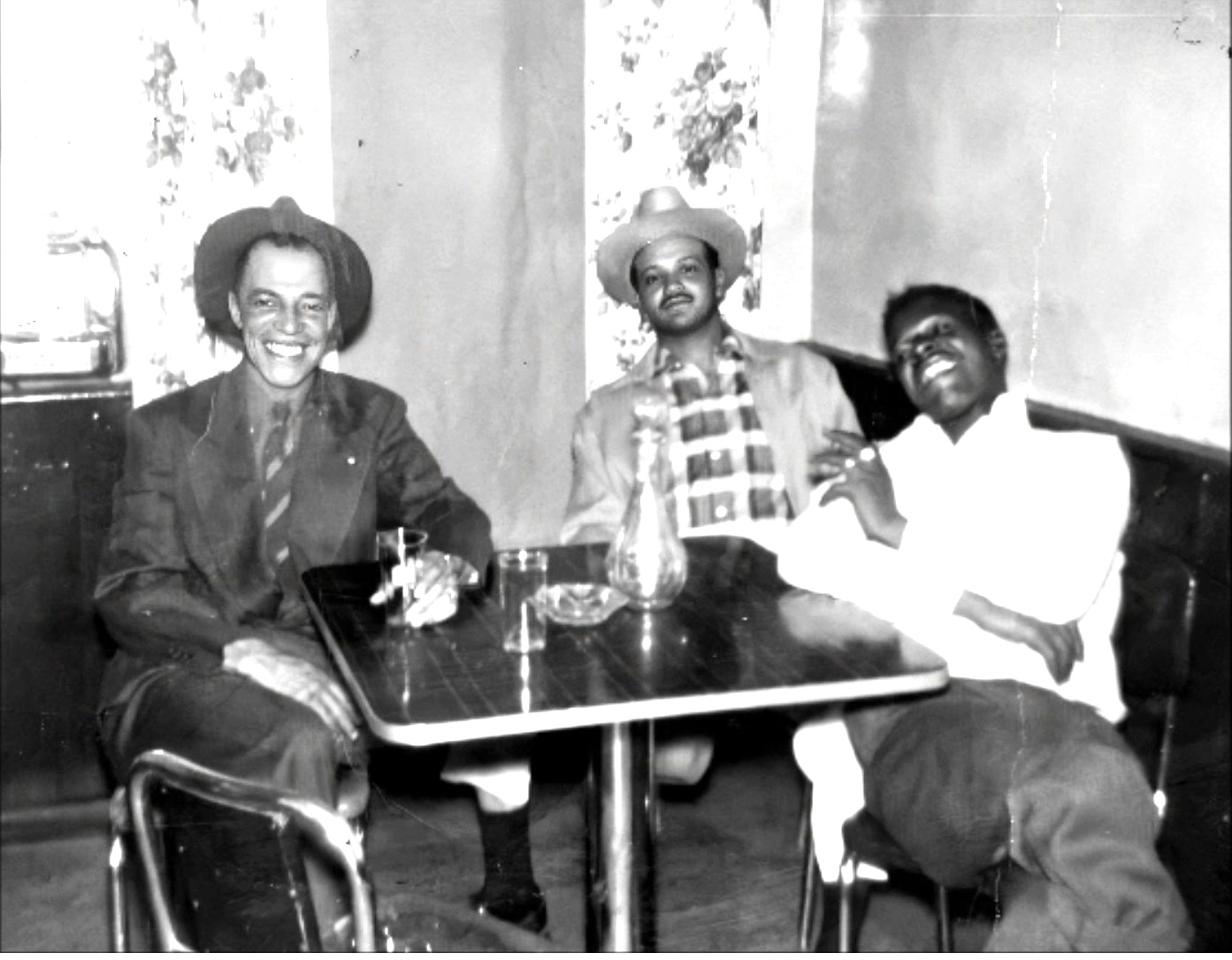

Kirchner said Michael Hughes, president of the DBCAAHS, has been a leader in collecting history of the African American business district, such as photos, and telling the district’s history. The DBCAAHS has recently acquired a space at 108 N. Second St. in the old Henson Hotel. There, the society will be able to display paintings and photos that depict the business district and the African American community in the area more generally.

The African American business district was privately-owned land and began in the late 1800s. Because Jim Crow laws and segregation were the law of the land prior to integration, Hughes said at the district’s peak, it was a place for Black people in the area to feel safe together.

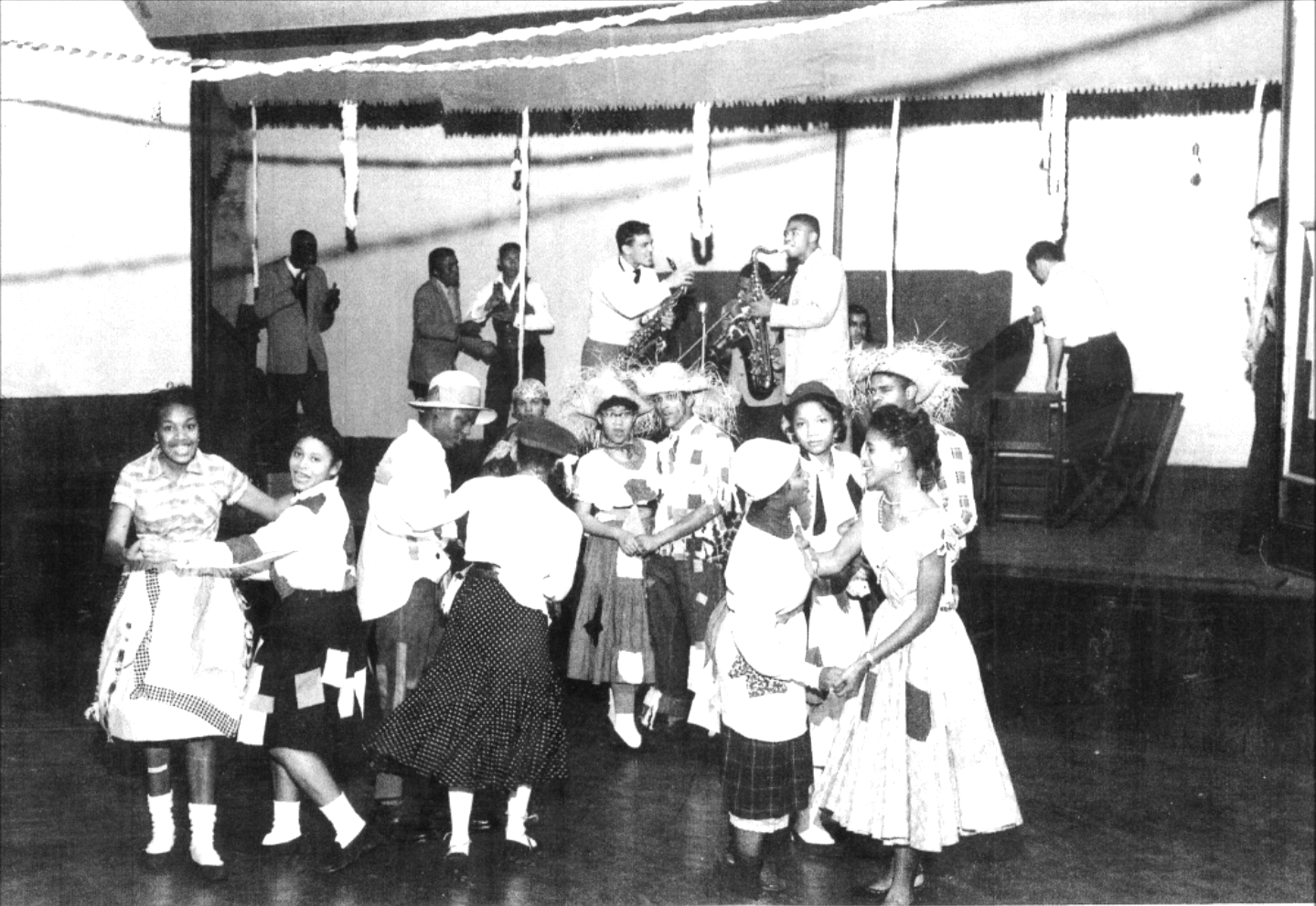

Especially in restaurants, often Black people weren’t welcome, Hughes said, so Black people found a sense of community in Black-owned restaurants and other businesses in the district. They established social clubs where they danced, held events and threw parties. If they worked jobs during the week in roles where they worked in white people’s homes, felt limited or did not feel respected or safe, Hughes said the business district was a place they could go over the weekend to have a good time. In photos of Black people spending time in the district, Hughes noted the smiles on many of their faces because they felt at home.

“They created their own world,” Hughes said.

The district stood, with its bustling restaurants, doctors’ and lawyers’ offices, grocery stores, barber shops and other Black-owned businesses, as well as largely Black neighborhoods, for about 80 to 90 years, Hughes said, until in the early ‘70s urban renewal came into the area and bought up the property. Hughes said many people in the community at first were enthused with the idea because they were under the impression urban renewal would rebuild and renovate the buildings and sell them back.

“But they didn’t do that,” Hughes said. “They cleared the land and sold it to the state, and in that, they dissolved all the buildings and all the business opportunities that was there for Black folks.”

Hughes said in a program he did with Centre College students, in their research they found the city had wanted to “clean up” neighborhoods around Second Street because the city felt like white people wouldn’t visit the district or more white people would visit Danville if the area were a park — they wanted it to “look good” to the white population. Hughes said Centre College was also behind the dissolving of the district to some extent, so it could expand.

Prior to integration, Hughes said there was a lot of Black wealth in the African American business district because Black people did a lot of business there, and in the ‘60s during integration when Hughes was a highschooler, the district started to look not quite the same, he said. By the ‘70s when urban renewal came into the area, he said the wealth that had been there wasn’t as strong, so there wasn’t the money and power to save it from urban renewal, and no one really stepped up to put up a fight.

With the loss of the business district, Hughes said a lot of Black people moved. The population of Black people in the city, Hughes said, divided in about half. It was difficult for them to get jobs other than in cleaning, working in kitchens, washing dishes and working in white people’s homes.

“And they didn’t want that,” Hughes said. “They wanted better things, so a lot of them moved away.”

Now with the partnership with N.C. A&T, Hughes said he’s proud of what the DBCAAHS has been able to accomplish, noting the society started with sharing historical photos of the African American community of Danville and Boyle County on Facebook, which people had wanted to learn more about, to help the memory of the district live on.

“It means a lot,” Hughes said about the partnership. “It means that we have done the work, you know, we have done the work.”