‘Diseases of despair’: Professionals talk about why National Suicide Prevention should be observed this week — and every week, going forward

Published 6:47 am Friday, September 14, 2018

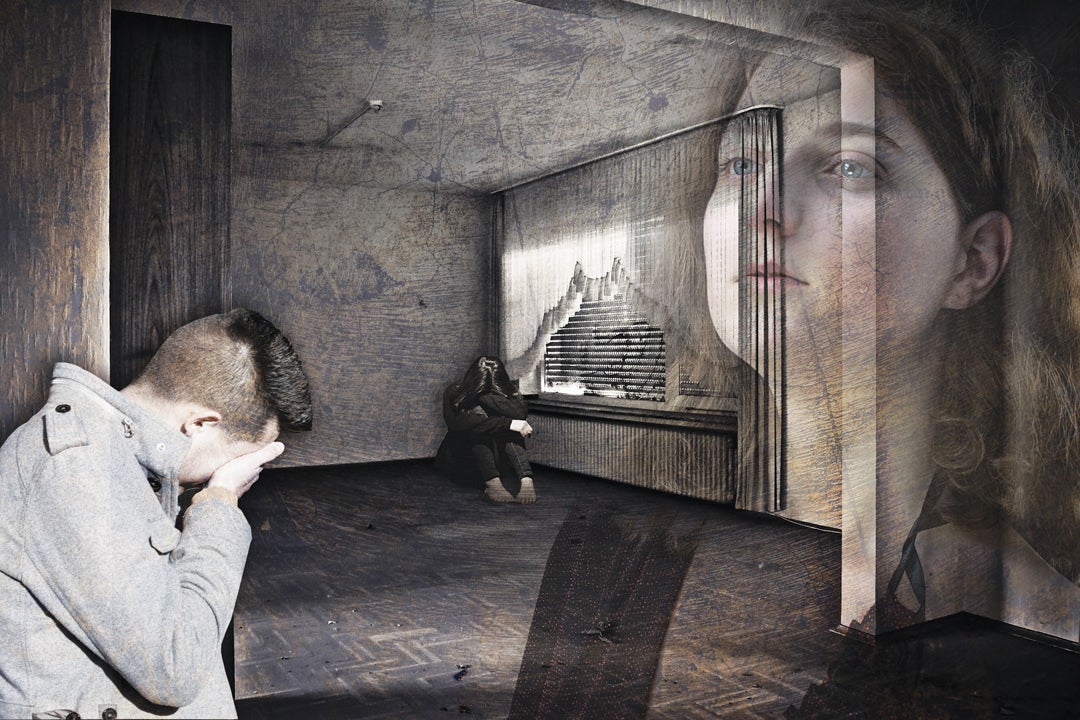

- Graphic by Akasha Goins

Editor’s note: This is a two-part series about suicide prevention. Check back in the weekend edition for an In Focus feature with a mother who lost her daughter to suicide.

National Suicide Prevention week began Monday and is observed through Saturday, but for many organizations the work never ends. According to the Cabinet for Health and Family Services (CHFS), annually, more than three times as many people die by suicide in Kentucky than by homicide.

Kathy Miles, a local mental health and substance abuse professional, is a trainer for QPR, a nationally recognized training that stands for “question, persuade and refer.” It’s an evidenced-based program aimed at preventing suicides by teaching everyone — not just the professionals — how to recognize warning signs and know what specifically to do in order to intervene and help someone get the help they need. She says more than 2 million around the world have taken the “gatekeeper” training, a term referring to anyone who comes into contact with someone considering suicide.

“It’s not a mental health professional training. It can be taken by teenagers or adults of any age, by the general public. So many have not had any training in prevention, and there are several trainers across the state who can lead it. I am just one of many.”

The trainings are generally set up by a specific organization, like the ones Miles did for pastors that was sponsored by the group she heads, ASAP, and Hope Network in January. Or trainers can decide to open them up to the public. Those interested can also access an online QPR gatekeeper training.

“Suicide is like the drug crisis — everyone you talk to has been affected by it,” Miles says.

According to CHFS, Kentucky ranks 16th in the most suicides. In 2017, there were 776 reported, which means 17.06 per every 100,000 people, which is over the national average of 13.26.

She says there are some interfaces between the drug crisis and suicides. For instance, some of the overdose deaths may actually be suicides. Miles says for anyone questioning whether they are seeing the warning signs in someone, they can visit afsp.org, which gives a quick list.

The site lines out signals to be aware of, such as how the person talks, their behavior and their mood. The obvious, of course, is if they talk about taking their own life. Others in the “talk” category include if they say they feel hopeless; have no reason to live; are a burden to others; feel trapped; or have unbearable pain.

Behaviors include an increased use of alcohol or drugs; possible online search for ways to end their life; withdrawing from activities; sleeping too much or too little; visiting or calling people to say goodbye; giving away prized possessions; aggression; and fatigue. Mood signals include depression; anxiety; loss of interest; irritability; humiliation/shame; agitation/anger; or relief/sudden improvement.

“The more of these signs you see together in a short amount of time in the same person, the more concerns you should have,” Miles says.

In Danville, Centre College uses the QPR approach. All of their resident assistants are trained, which Miles does, as well. But — she’s only one person. She doesn’t get paid to do what she does with suicide prevention; she’s just passionate about it. She says there are several organizations that can provide trainers or get out more information to those, depending on the sense of urgency.

In an immediate emergency in which there’s a suicidal risk, Miles says always call 911; going to the ER is another step to take, as well as several emergency hotlines.

The best way to prevent suicide is “to be open …” Miles says. “… Yes, it can be occuring around you. It is one of the diseases of despair. Not a very happy term, it’s a national term, but it is what it is.”

…

Stacy Blaketer is the Medical Reserves Corps coordinator with the Mercer County Health Department. MRC is a national network of local groups and volunteers who engage communities for several goals, including to strengthen public health.

“We’re doing a couple of things …” Blacketer says, and one of those is focusing on the QPR trainings, which she’s had a few volunteers go to, and will be offering one to the general community in November.

“A couple of those volunteers have experienced suicide first-hand in their families. They wanted to see it in the schools and felt some of the students and volunteers should have the training, as well.” MRC partners with the Harrodsburg Area Technology Center, the vocational school in Mercer, to teach the HOSA-Future Health Professionals group to address bullying and suicide issues inside the school.

Blacketer says one volunteer in particular, Chris Claunch — who lost her daughter to suicide last year — felt it was important to start the training when they’re young, as students. The HOSA students will bring what they’ve learned back into the elementary schools, as they feel kids sometimes learn best from kids. They constructed an anti-bullying pledge and created a banner, where kids could sign their names, signifying they pledged “to do the right thing.”

“From working with these students the past several years, I hear about bullying a lot,” Blacketer says, a presence that seems to go hand-in-hand with suicide rates. “We have found that in past situations, if they feel like they’ve been bullied and there’s no hope, sometimes it does end up in that type of situation.”

Blacketer says they’ve found that kids will text their feelings to others before talking face-to-face. They’ve been promoting the Crisis Text Line, a free 24/7 hotline that’s used by texting “home” to 741741 from anywhere in the U.S. to reach a trained volunteer. “We found that it was actually a great response mechanism, after we tried it out ourselves. You get a response almost immediately,” she says.

A training for QPR will be held 5:30 p.m. Sept. 27 at the Mercer County Health Department, and Blacketer says anyone from any community is welcome to attend.

“My theory is the more people who know about it, the better off everyone will be. People can take this training and then use these skills out in the community,” Blacketer says. “If you could have one person trained in every household, it’d be wonderful. This is our start to get the word out.”

She asks that anyone who wants to attend RSVP her at stacyc.blacketer@ky.gov, or call (859) 734-2229, ext 139.

“This has sort of morphed into my job. I just know in the community — I personally have known friends who have committed suicide. You hear about it so much.” Blacketer says in the past, suicide was a thing “you didn’t talk about. I feel like it needs to be talked about. It will help people to be able to open up about it and their feelings.”

She says maybe since the “numbers are rising so much in Kentucky, maybe we can talk more openly about it — with coworkers, friends, family, neighbors; everyone. You have to realize there’s a problem to get to the solution.”

…

Don Rogers, chief clinical officer with Bluegrass.org, which locally serves Boyle, Lincoln, Garrard and Mercer, says it’s true — overdose deaths from opioids have replaced their top concern of suicide risk.

“But it’s not that suicide risk has gone down any, but that the overdose death rate is close to twice as much.” If someone calls in as a suicide risk, they get them in the door right away, he says; it’s treated as an emergency.

Suicide deaths have increased over the last 10 years — a nationwide phenomenon, Rogers says. On average in Kentucky, one person dies by suicide approximately every 11 hours, according to CHFS. It’s the second-leading cause of death for ages 10-34.

So Bluegrass.org has a mobile, 24/7 crisis line, a service they use mostly internally for the highest-risk clients who are in crisis but not quite in need of hospitalization.

Bluegrass.org also has a statewide program called the Jail Triage, started in the early 2000s after a string of jail suicides. For everyone who’s booked, there’s a suicide screening process; if they flag a certain score on the items, the jail puts them on the phone with one of Bluegrass.org’s staff members, who comes up with a recommendation of a plan.

“It’s a huge deal. In Fayette County, we have staff 24/7 who monitor people at risk in the jail. Since the program was started back about 20 years ago, there’s been three or four total. Prior to to that, there were multiple suicides every year.”

Rogers says a fact about suicide is “not everybody who dies of suicide has a mental illness. A substantial number of them don’t have any. We target the veteran and military population as part of that.” Bluegrass.org has distributed trigger locks — a device gun owners put on a gun that prevents it from being discharged, and they can give the key to a family member or friend.

“You have to think about it really hard if you want to do it,” Rogers says. “Means reduction is the best standard intervention — taking away the means by which someone can kill themselves.”

He says the myth that “someone who really wants to die will find a way, that doesn’t really bear out on the research. What bears out is if you have quick access to a means, you’re more likely to die.”

Rogers says in Lexington, Bluegrass.org has posted their crisis line number and a hopeful, uplifting message in places like parking garages, a common place people take their own lives, because they’re less likely to be found by a family member.

Bluegrass.org’s 24-hour crisis line is (800) 928-8000.

IF YOU NEED HELP

The following are 24/7 crisis lines if you or someone you know is experiencing thoughts of suicide:

• Text “HOME” to 741741.

• Bluegrass.org’s 24-hour crisis hotline at (800) 928-8000.

• The National Suicide Prevention hotline is (800) 273-TALK (8255).

SO YOU KNOW

• To find out more about the warning signs, visit afsp.org.

• To find an area trainer for QPR training, visit www.qprinstitute.com, call Bluegrass Prevention at (859) 225-3296, or email suicideprevention@ky.gov. To access a local community mental health center, call Comprehensive Care at (859) 236-2726.